Precision-scheduled railroading (PSR) has been transforming the rail industry for years with its cost-cutting measures and its promise of more efficient operations. The rail carriers implementing these techniques continue to sing PSR's praises in recent calls with analysts.

"We implemented it flawlessly," Norfolk Southern CMO Alan Shaw said in January.

Sticking to the principals of PSR will allow railroads to handle large volume swings without using more equipment, Union Pacific CEO Lance Fritz said in February.

Even more recently, Kansas City Southern (KCS) stated the principals of PSR will help it to weather the coronavirus and its impact on the rail industry. The work done with PSR has put the company "in just outstanding position to respond to this latest extraneous curveball that we've been dealing with and the rapidly changing business environment as put us very much on our toes," CEO Pat Ottensmeyer said on the company's earnings call last week.

Shippers have been skeptical of the transition to PSR, though, which has required them to transition their operations to comply with the railroad's schedule.

"They may claim that PSR improves service but our experience and that of many other shippers has been the opposite," Emily Regis, fuels resource administrator for the Arizona Electric Power Cooperative, said at a congressional hearing last summer. Arizona Electric Power Cooperative stuck by these comments when contacted by Supply Chain Dive with the opportunity to update the statement.

The implementation of PSR will vary from carrier to carrier, which means not every shipper will have the same experience, said Dustin Burke, a member of Boston Consulting Group's (BCG) operations practice who completed a report on PSR in March.

"Our perspective is that PSR has common principals in terms of how it's been applied," he told Supply Chain Dive, "but it has a lot of diversity within it across the different railroads."

These common principals are:

- Simplify and balancing the network.

- Maximize asset utilization.

- Control cost.

- Reduce complexity.

- Culture change in the leadership.

Railroads have relied on operating ratio as the major metric of success for a PSR transition. Still, no railroad has been able to hold OR "better than 60% over the course of several quarters," Burke said, suggesting this can be hard to sustain over time.

Executives often cite speed, dwell and cars on line as other measures of success. An analysis of rail surface data from the Surface Transportation Board (STB) showed the early adopters of PSR followed through on those promises. STB data only includes a rail carrier's U.S. network and some carriers calculate the figures differently for their internal financial metrics, but the STB provides the only centralized database of rail figures.

"Our transportation plan made it difficult to provide on-time service and we recognized the need to change," a spokesperson for Union Pacific told Supply Chain Dive in an email. "We transformed our network by working smarter, eliminating needless delays in rail terminals and keeping rail cars moving."

Speed

If locomotives are moving faster, containers get where they need to go sooner, which railroads say will benefit shippers. Trains are making fewer stops under PSR, which is one reason for the increased speed, according to Kenneth Turner, the president of KTT Rail Consulting.

Trains have to power down and potentially reshuffle equipment when they make a stop, which slows them down.

"They don't do that now," Turner said. "They're not stopping as many times as they used to in the old-style railroad."

Before PSR, railroads focused on train length and would cancel trips if a train didn't meet specific length requirements. Under PSR, the focus has moved to cars and specific schedules, Union Pacific explains.

"What railroads found is that the focus on moving trains was actually slowing down the network overall and causing cars to sit for long periods of time in yards (a measurement railroaders call “dwell”) — and that’s inefficient for both railroads and their customers," the railroad says on its website.

Kansas City Southern saw its speed decline year-over-year (YoY) in 2019, but it was still the fastest rail line in the U.S. So what's it doing differently?

"Nothing out of the ordinary that I'm aware of," Turner told Supply Chain Dive. But the rail line did bring on Sameh Fahmy, the executive vice president for PSR, who worked under Hunter Harrison, the father of PSR, while at Canadian National.

Dwell

As the name implies, PSR requires every shipment to be on a schedule. Tighter schedules reduce the need for hump yards by reducing the time loads are separated from arriving trains and sent to different departing trains.

"So let's say if you went from New York to Los Angeles," Turner said. "And before it used to be 10 days, because it would go through, let's say, five classification yards to get it humped and to get it reprocessed. Now, with precision railroading, you're going to move a car faster."

Every time a railcar stopped in a yard it was collecting dwell time. The ability to bypass yards can send dwell time from as high as 48 hours in some cases to zero, Turner said.

Railroads say reductions in dwell time and increases in speed are leading to improvement in getting shipments to their destinations on time.

"Car trip compliance improved nine points year-over-year driven by increased freight car velocity and lower dwell demonstrating our team’s commitment to delivering a consistent and reliable service product for our customers," Union Pacific COO Jim Vena said on the company's January earnings call.

BNSF, which actually became slower and saw an increase in dwell time, blamed the decline on natural events.

"BNSF experienced some well documented historic flooding and other significant weather challenges that impacted our network in 2019," a company spokesperson told Supply Chain Dive in an email. "However, we finished the year with strong gains in our overall service performance and continue to see improvements in our operational metrics."

In 2016, CSX ranked the lowest for speed and dwell time, a company spokesperson told Supply Chain Dive. It's now in the top three for shortest dwell and fastest speed.

"This transformation was achieved through a combination of better network design and daily execution by our dedicated team of CSX railroaders," the spokesperson said. "Importantly, it was this execution that truly enabled CSX to implement our improved operating plan that balanced the network, streamlined operations, and removed millions of unnecessary touches."

Cars on line

Improvements to speed and dwell are coming as most Class I railroads are decreasing their cars on line. The value is a measure of freight car inventory and includes cars on trains, in yards, at a customer location or in storage, but cars could be empty so its not a measure of volume. Less equipment means savings for the railroad.

"The increased network velocity, improved fluidity, and fewer locomotives and freight cars on the network drove $15 million in savings associated with equipment rents and $12 million in savings of material cost," Norfolk Southern CFO Mark George said on the company's January earnings call.

The railroads' ability to increase speed and decrease dwell time means the railroads don't need as much equipment, Turner said.

"If you can turn a car five days quicker across the country, that customer ... doesn't need as many rail cars in their inventory because they're turning them quicker, because they're more efficient to speed, less handling and less downtime," he said.

Fahmy echoed this last year on an earnings call. "These improvements [to velocity and dwell] allowed us to take assets out," Fahmy said. "We took out 14% of our locomotives. So now we have an active fleet of 903, when we started the PSR exercise it was 1,046."

Still, BNSF and Union Pacific, which tend to move more volume than the other railroads, used substantially more equipment in 2019.

The reduction in cars online, the elimination of hump yards and workforce reductions have also allowed carriers to cut cost and has led to improved ORs, Burke said.

What faster rail means for shippers

In 2019, the majority of Class I railroads reduced dwell time and became faster. But do shippers care? They should if they operate a just-in-time inventory operation, Turner said.

"They want to know that their product is scheduled to arrive at the customer's doorstep at [a specific] time, and they can bank on that," he said.

The YoY improvements suggest railroads are getter faster with less dwell and equipment. The rail companies insist this is an improvement for their customers. And Turner agrees shippers will likely see faster and more reliable service as a result. Some shippers, though, might experience growing pains as the transition happens.

"You do see better performance across the network, which should lead to a better and more reliable product," Burke said. "Freight moving faster is a better product on rail. And it has long been one of the theories of PSR that that in and of itself will help to drive growth because the better product will bring more volume."

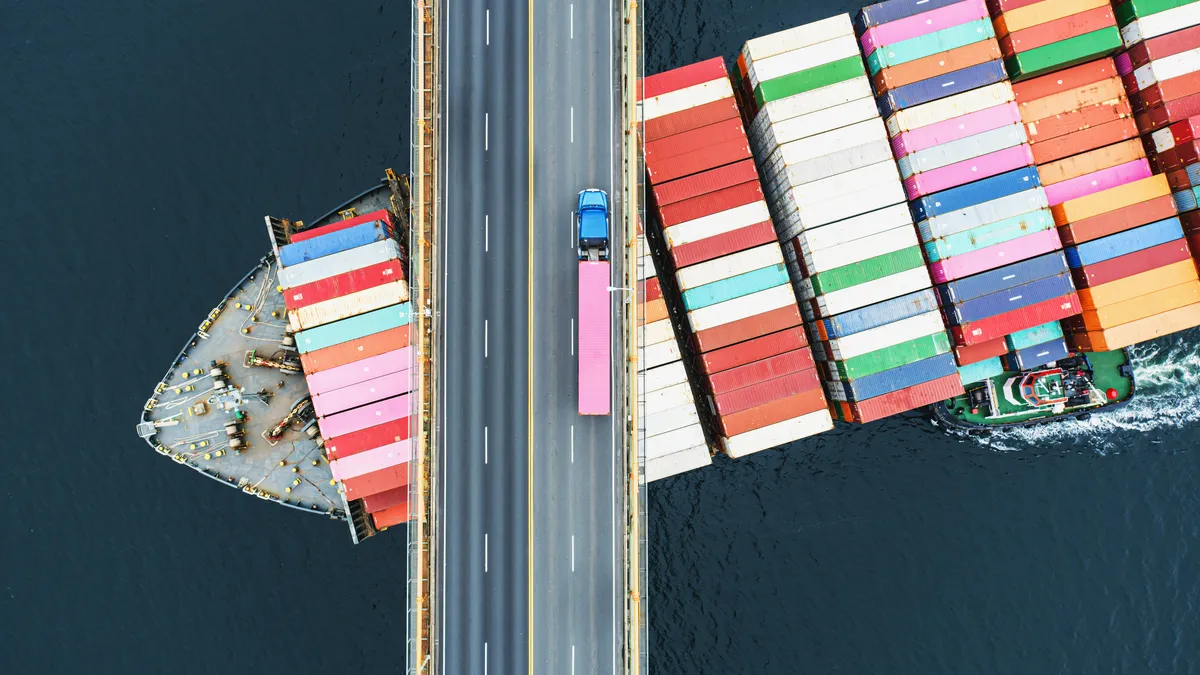

But there are still some things carriers can change to continue to improve, he said. This includes thinking about further integration with intermodal and trucking companies to give customers more end-to-end solutions.

"Customers have alternatives," he said. "And if we believe that the cost of trucking over long distances will be quite a bit lower, you know, 20 years from now than it is today then I think rail needs to rethink how it competes for that part of the business."

Railroads should also increase their focus on visibility with further investment in technology talent, automation and artificial intelligence, he said.

"We are not saying that PSR has to stop or is going to go away, if anything we think its been impressive the results that have been demonstrated," Burke said. "But when you see such success you start to get concerned about a plateau and with a plateau you need to think about the next wave of improvement."