Editor’s note: This story is the third installment of a series exploring global trade shifts. Read the previous story here.

A new wave of supply chain shifts is spreading after the pandemic, and behind it lies a complex set of global business decisions made to optimize operations.

Companies had been considering production shifts for years, even before 2020. Now, as firms crawl back from an unending list of disruptions, experts say those decisions have accelerated as cost pressures, policy incentives and new ways of thinking recently converged to influence supply chain resilience strategies.

For some, those goals include de-risking their operations from geopolitics after several high-profile wars and coups have shaken up logistics. For others, moving sourcing, logistics or production networks is a means to chase lower costs, emissions and lead times all at once.

Most, however, see their decisions driven by a combination of factors. Here are six of the most prominent reasons experts cited in conversations with Supply Chain Dive.

1. A new way of looking at costs

Supply chain shifts have long been opportunities for companies looking to cut costs, and cost assessments remain the leading factor behind network shifts, according to every expert interviewed by Supply Chain Dive.

Costs have been rising across the board for the past few years. In the past decade, supply chain managers have dealt with global trade wars that have inflated the price of commodities, international freight rates that skyrocketed during the pandemic, and consistently rising wages in major manufacturing hubs like China and Mexico.

Altogether, the growing costs tipped the scale for many companies’ considerations of the optimal country to source from, according to several experts. Now, business executives are rethinking the KPIs they use to assess supply chain choices, and considering whether terms like “total cost of ownership,” “landed costs” and “revenue impact” are better suited for modern trade dynamics. So far, while no single term has risen to ubiquity, each variation highlights how executives are seriously factoring in the costs of tariffs, transportation, product lead times, brand risk, emissions, among other factors, into network design decisions.

“It was sort of a gradual process [of] companies becoming aware and starting to quantify all the costs and risks that offshoring encompassed,” said Harry Moser, founder and president of the Reshoring Initiative. “It wasn’t just one of those things, it was the aggregate of all that stuff that caused them to decide to bring the work back.”

How global landed costs compare for US shippers

2. Tariffs and subsidies

Tariffs and subsidies are two sides of the same coin, and the past two U.S. presidents have used both to alter the shape of supply chains.

The financial penalties and incentives amount to a bipartisan carrot-and-stick. President Donald Trump’s administration used tariffs as policy tool to force global trade conversations, and penalize importers from sourcing products from cheaper markets abroad. Most notably, section 301 tariffs targeting China added a 25% duty on hundreds of products. However, rather than revoke the tariffs on a partisan basis, President Joe Biden kept the tariffs in place alleging discriminatory trade practices — and offered companies billions of dollars in federal incentives to tip the balance of production back to the United States.

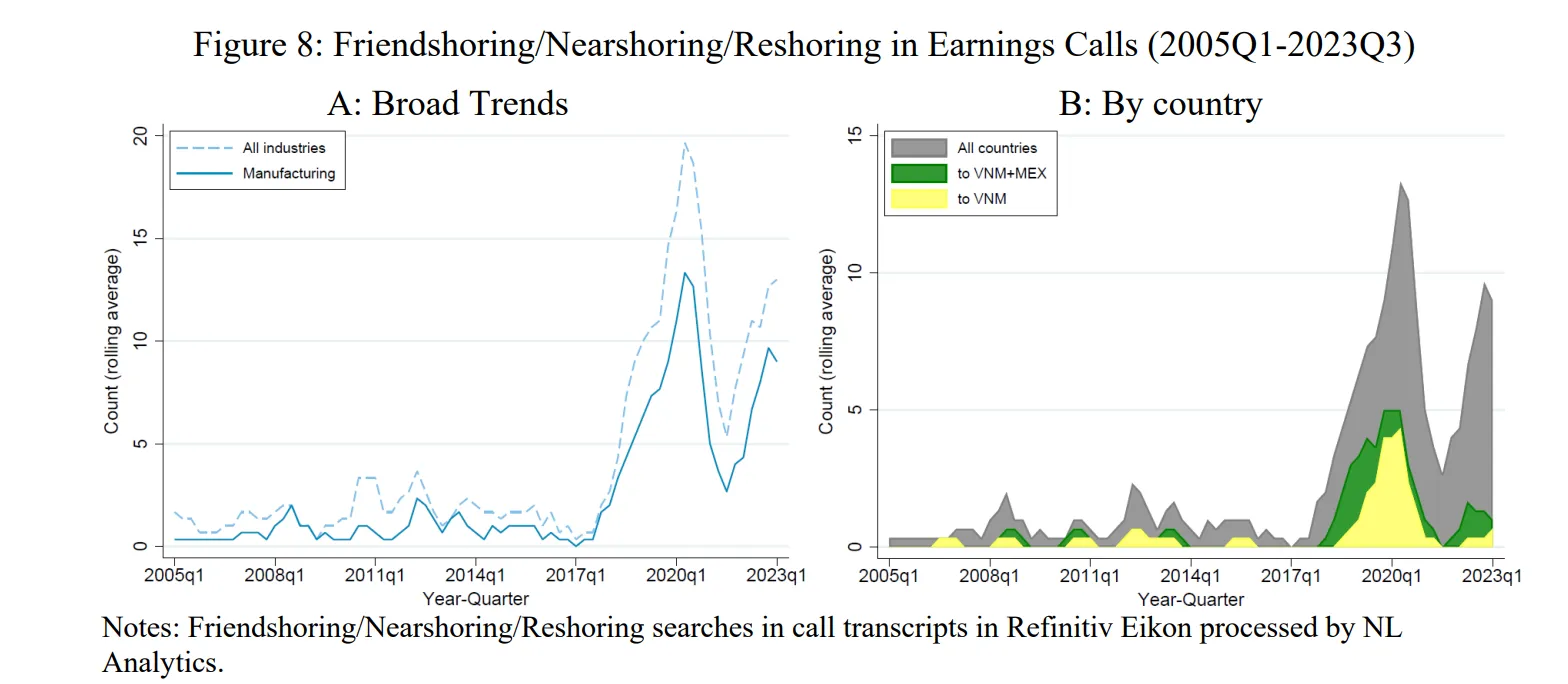

Such rare consistency in industrial policy from the U.S. led many companies out of a “wait-and-see” approach in the past few years, according to an economic research paper presented in August at the annual Jackson Hole Economic Symposium.

“Biden didn't get rid of the tariffs and Biden gave subsidies,” said Laura Alfaro, the Warren Alpert Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School, and one of the two authors behind the research paper. She emphasized those two actions gave companies certainty and effectively told them: “It doesn't matter who's gonna win the next election, they will get tariffs and subsidies.”

That certainty was important to spur a wave of investments since 2017. Companies reacted to the section 301 tariffs, the pandemic, and several other factors to move production out of China. According to the research paper, investments went to:

- Nearby low-wage countries in Asia like Vietnam;

- Locations closer to the U.S. like Mexico and Canada;

- Or to other destinations that had a market capable of absorbing new capacity for key industries, like Ireland, Switzerland and the United States.

“Many firms were leaving China because China has developed and development is to pay higher wages,” Alfaro said. “But there is no doubt that there was a push in the last five years due to policy.”

As China's market share fell, other countries worldwide won out

3. Geopolitical risk

Concerns around tariffs and the rise of subsidies also highlight another emerging risk factor in modern supply chain decisions: geopolitics.

“The thing that's really in people's minds at the moment now is geopolitical risk. And that of course — it relates to tariffs, but it's also country risk,” said David Shillingford, co-founder at Everstream Analytics.

The U.S.-China trade war was but one of a rising number of geopolitical flashpoints that have threatened the global flow of supplies. In the past three years alone, executives have had to navigate extreme disruptions to production from protracted lockdowns or regional conflicts like the Russia-Ukraine war.

Throughout the pandemic, companies “saw what it was like [for orders] to be a week late or a month late,” Moser said. Now, he added, companies are realizing “it could be you're never going to get the things you ordered.”

Such geopolitical risks are why consultants like Moser and The Boston Consulting Group began offering their clients new resources, attempting to grade countries by their “risk level.” Moser’s version, for example, grades countries by their likelihood of having a prolonged interruption, where a U.S. buyer could not get in touch with their foreign supplier.

Geopolitical risk is significant in a few countries, regions

Moser said he advises executives to think about the number of sales that could be lost from a prolonged interruption to a country. Then, ask if “you can justify paying moderately more, 10 to 15% more, as insurance to make sure that you have the components to be able to make your product sell.”

However, other experts have warned geopolitics are far from the leading factor on executives’ minds, as companies make investment decisions not based on a two- or four-year time frame, but rather a ten- to fifteen-year assessment.

And even if an executive wanted to protect against geopolitical risk by, for example, fully de-coupling from China, several experts warned doing so is tough without full visibility into tier 2 and tier 3 suppliers. After all, companies in China are driving both imports and greenfield investments in countries like Mexico and Vietnam as they chase shifting U.S. demand.

“If you're making a decision to reshore, you're basically putting steel in the ground, you're putting that in the ground for at least the minimum of 15 years before you have your return on investment. On a timeline of 15 years, political stuff doesn't matter,” said Patrick Van den Bossche, a partner at Kearney.

Still, even if not the leading factor for executives, the topic continues to be a crucial one among policymakers — a fact that has had powerful repercussions for supply chain designs.

4. Existing supply networks

With so many countries competing to be production hubs, how do executives pick the best location for their supply chains?

A country’s ability to absorb new production capacity is top of mind for executives making production shifts, and that’s a big reason why countries like Mexico and Vietnam, with a strong existing share of exports to the United States, are winning even more business.

Take Mexico for example. The country has long been an industrial hub for goods like auto parts, which means companies are more likely to find legal support to operate as well as workers with industry-specific skills.

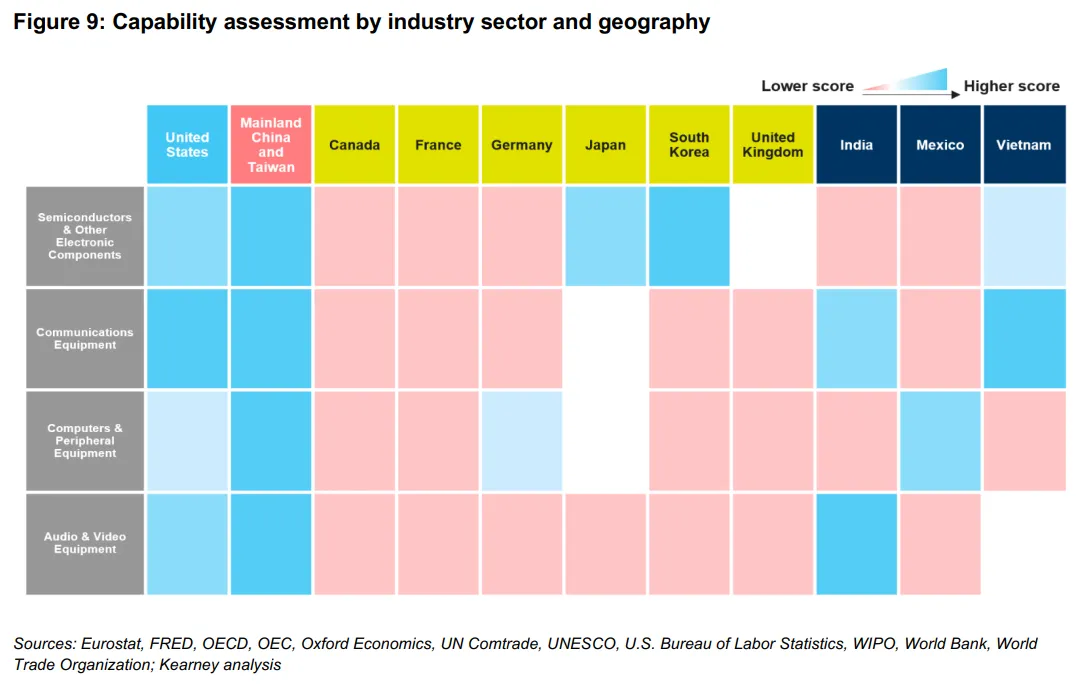

Such a history also makes the country a more competitive choice than the United States in sectors like electronics, experts said. In fact, a Kearney analysis found that the United States cannot alone support an entirely reshored electronics industry supply chain.

“To supply just the U.S. market by 2030, you would need more than $500 billion in investments and 10 times the increase in workforce,” said Van den Bossche, who led the Kearney study on electronics supply chain resiliency for the Consumer Technology Association. He added such a feat would be difficult not just from a monetary standpoint, but also because the U.S. manufacturing industry continues to struggle to fill jobs.

Instead, a “team approach” is needed to meet mid-term resiliency goals, where U.S. investments are spread out across the various countries best suited to quickly absorb new capacity, according to the study.

“All the stuff you've seen with alt-Asia and China-plus-one, China-plus-two, is a lot more of ‘move a little bit over to other countries and see if we can maybe start building an ecosystem similar to the one that China has been building for the last four decades,’” said Van den Bossche.

Similarly, multiple research papers have found countries in Europe, Asia and North America that are benefiting from supply chain reallocations have one thing in common: They are primarily winning market share in sectors they already have a strong presence in.

5. Lead times and agility

In addition to tariffs and subsidies, executives are also considering the need for speed and supply chain agility, as many saw just how quickly demand patterns shifted throughout the pandemic, according to several experts.

While companies have been investing in technology and other practices to better forecast category demand, during the pandemic many found accurate forecasts meant little if inventory was not at the right place at the right time. And though congestion at ports and warehouses — which passed as demand receded — were often to blame for long lead times, logistics managers operating in the high-pressure environment increasingly made decisions to cut lead times where possible.

In some cases, companies chose to rework their logistics flows to import and store goods closer to the consumer markets they were serving. Then, a push to nearshore production followed, with many companies touting the advantages of having products stored or produced close to the next step in the supply chain as a boon to agility.

For example, Hydroflask-maker Helen of Troy has sought to nearshore some of its bottle production in the past year, relocating it from China to the Western Hemisphere.

“This will help us diversify geopolitical risk, enhance our responsiveness and reduce inventory,” COO Noel Geoffroy said in a July earnings call. “These moves also create value as they can provide quicker transit times, greater speed to market, scale advantages and process standardization.”

6. ESG goals

While not the leading factor, environmental, social and governance goals or concerns are being increasingly considered when changing supply networks, according to several experts.

“Sustainability is more top of mind now than it was when these systems were originally designed. So the redesign is more sustainable or greener in effect,” said David Correll, a research scientist and lecturer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Center for Transportation and Logistics.

Part of the reason is that nearshoring, friend-shoring and reshoring efforts could also have the side effect of helping cut down on several layers of emissions and brand risk.

A facility move from China to the U.S., for example, could simultaneously result in fewer transportation services utilized and fewer emissions per kilowatt hour of electricity consumed at production plants, due to the United States’ energy mix, according to Moser. And, Shillingford pointed to companies’ need to avoid sourcing from the Xinjiang region of China to ensure compliance with the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act.

“If you want to see companies that are taking action, look at the the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act,” Shillingford said, noting companies affected by it run a very real risk of having inputs held up or sent back, which translates into direct and immediate costs. “And it’s happening.”

Some experts warned moving supply chains is not a panacea for sustainability. In fact, moving a facility from one country to another could result in more emissions if tier 2 and tier 3 suppliers don’t follow suit. However, others acknowledged executives were increasingly prioritizing sustainability, citing recent surveys as evidence for the inclusion of ESG goals into supply chain design decisions.

“It used to be, you know, you invest X and you see return Y,” Van den Bossche said, adding now executives acknowledge you returns may be lower and costs may not be cheaper, but “you can service your customers better. You are closer by so you can have more innovation. And you have a better ESG score.”