The Sept. 11 terrorist strikes were a wake-up call to the government that our borders weren’t secure.

Suddenly, every plane, ship and container became suspect. Back then, vessels carrying freight would arrive at U.S. ports uninspected, and containers’ contents were often unknown to Customs and Border Protection (CBP). Then, the looming threat of terrorism forced the government to demand more information, placing the burden of security on supply chains.

Yet, the post-9/11 supply chain has arguably become much more efficient today than it was before the attack, according to Jon Slangerup, Chairman and CEO at American Global Logistics. In identifying shippers – collecting and sharing data in the process – and better understanding the cargo hand-off points, government agencies and industry stakeholders worked together to improve safety without compromising the speedy movement of product.

“What we encountered since 9/11 was an understanding of how silo-driven the management of those supply chains were, and to some extent still are,” Slangerup told Supply Chain Dive. “The various agencies involved in protecting people and assets pulled together very quickly.”

In the sixteen years since 9/11, these gained efficiencies have translated into bottom-line gains, as the cost of shipping as a percentage of a product’s total cost has fallen. Here are five of the main changes that made this happen:

Data led to supply chain efficiency

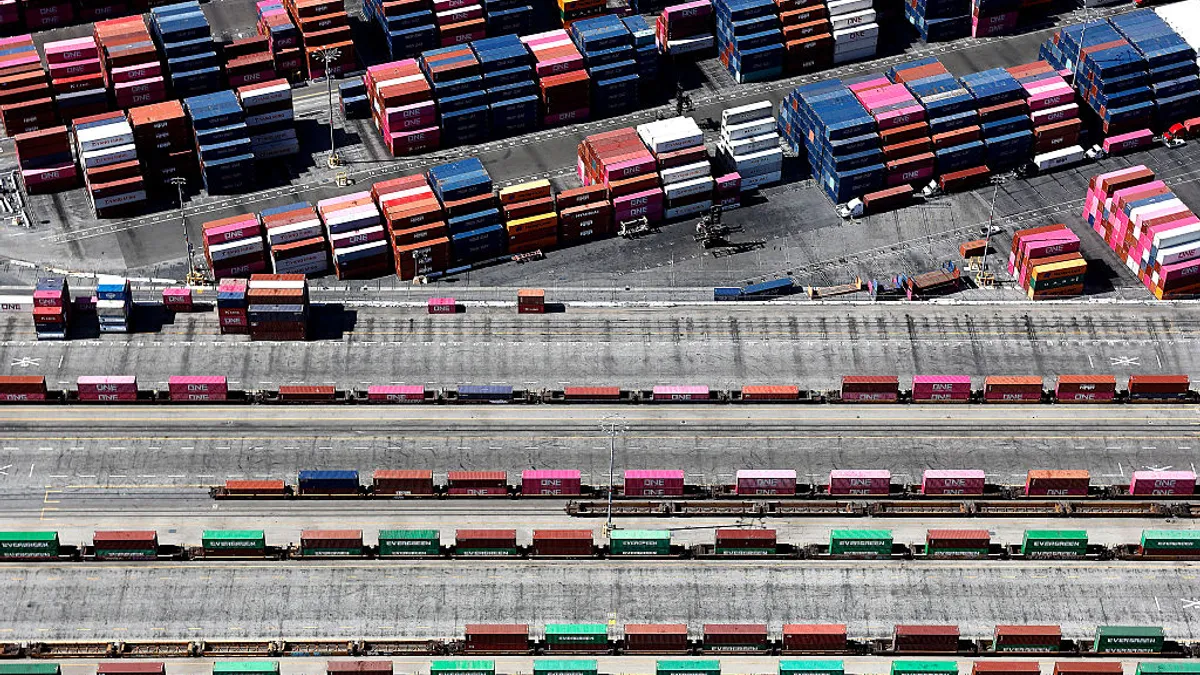

Since 9/11, there’s been a lot of attention paid to the points where cargo changes hands: from origin of manufacturing, to shipper, to marine terminal for loading, to ocean carrier, to marine terminal for offloading, to rail and trucking, to the warehouse and distribution centers.

“That’s where the risk and cost lie,” said Slangerup. Once the cargo is on a vessel, the content is already known and screened. With increased pre-shipping data requirements due to post-9/11 security concerns, the supply chain was forced to create efficiencies in the hand-offs, where money and time are often wasted, said Slangerup. As a result, the cost to move goods is a smaller proportion of the sale price to the end user than it was 10 years ago, he said.

It’s the data that’s driving deliveries, as opposed to physical drop-offs and loading.

Geoffrey Powell

President, National Customs Brokers & Forwarders Association of America

Information and data leads to visibility and answers as to when a shipper can expect their goods to show up on the dock or warehouse. Using data, companies can see where the breakdowns occur in the supply chain, to make corrections.

The ocean shipping industry is taking more time from a visibility perspective than the air industry, because of the multi-nation integration needed to share information without giving away a competitive advantage. Like the airline industry has already done, the ocean side is now forming alliances to help integrate information and cross-sell.

“This revolution of information started with the small package industry in the early 1980s, with companies like FedEx and UPS,” Slangerup said. By the time of 9/11, those same companies already had significant information tools available to them to more easily comply with increased scrutiny. Those that didn’t have those tools in place had to scramble to get them. The air freight side was in better shape to do that than the ocean freight side, which is catching up.

Screening at origin

The Container Security Initiative (CSI) was implemented in January 2002. “It forced upstream the actual inspection or screening of containers at origin,” instead of inspection and risk mitigation left until arrival at the destination, said Slangerup.

U.S. Customs officers work with foreign counterparts at 58 foreign ports to assess container security before they’re loaded onto the vessels. When the cargo arrives onshore in the U.S., it goes through similar scrutiny. These actions dramatically improved the risk profile for moving ocean freight.

Interestingly, inspections have not delayed importing time to the U.S., said Geoffrey Powell, president of the National Customs Brokers & Forwarders Association of America (NCBFAA), which represents operators in international trade.

The reason? More advanced data. CBP has visibility via data on all the shipments prior to loading. The data package, including automated manifests and Importer Security Filings (ISF), and the entry package must be submitted earlier than in pre-9/11 days.

Advanced filings and timeline shifts

Before 9/11, exporters could deliver their cargo two days before vessel sailing, and get it on board. The documents and data weren’t needed until the ship sailed, or even a few days later. That’s changed. While an exporter might have a five-day window to deliver the cargo for loading, the data is required on day three, even if the cargo arrives on day four or five.

“That shortens the window and pressures companies to get the data out earlier. It’s the data that’s driving deliveries, as opposed to physical drop-offs and loading,” Powell said.

What would be the impact on us as exporters if they imposed this on us, and this became global?

Geoffrey Powell

President, National Customs Brokers & Forwarders Association of America

In 2002 the U.S. government started requiring advanced or automated manifests. All carriers have to submit these automated manifests to CBP before loading the cargo, to allow for electronic or manual screening.

In 2009, the government required ISF. “Importers (or shipping agents) became liable for the information provided to customs, before the goods arrived at the port,” said Powell.

Developing ways to reduce container examinations

In November 2001, the government developed a known importers program, which became Customs-Trade Partnership Against Terrorism (C-TPAT). The idea is for participating companies to benefit from fewer cargo examinations and expedited shipping when there’s a port delay.

While there’s not a similar program for exporters, that’s something that various U.S. agencies are working on, to show that companies are meeting export regulations.

Congress initiated the SAFE Ports Act in 2006, requiring that every container be examined prior to entry. Initially with this program, though, there was concern that ship traffic would back up, so the government has had to balance trade facilitation with security and compliance needs, said Powell.

Increased agency cooperation

“Cooperation is the most amazing thing to come out of this (post-9/11 security initiatives), and doing that in a way that did not affect the performance or efficiency of the supply chain,” said Slangerup. That includes multi-agency data integration and sharing, that goes beyond the U.S. borders. “The cooperation between the CBP and their counterparts across the various origin points of shipping has been remarkable,” said Slangerup.

The various agencies involved in protecting people and assets pulled together very quickly.

Jon Slangerup

Chairman and CEO, American Global Logistics

Slangerup, previously the CEO of the Port of Long Beach, said the level of domestic agency cooperation was also evident when they built a joint command and control center, holding Homeland Security, CBP, the Coast Guard and others. “They all co-share this facility, which has state-of-the-art surveillance, information and interdiction capability, combined around a common goal of protecting the integrity of imported and exported goods into and out of the US,” he said.

Freight scrutiny by other countries

While these changes focus on freight security coming into the U.S., the industry is also concerned with what other countries may require of U.S. exports, given the changes made in their ports.

CBP is a member of the World Customs Organization (WCO) and has been working with the other 180 members to try to standardize the process for all customs organizations. They’re working on an Authorized Economic Operator (AEO) program, which is a combination of the Importer Self-Assessment program and C-TPAT, for example.

“What would be the impact on us as exporters if they imposed this on us, and this became global?” said Powell.