This is a contributed op-ed written by Daniel B. Maffei and Louis E. Sola, commissioners at the Federal Maritime Commission. Opinions are the authors' own.

The word "unprecedented" has almost lost its meaning as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. But yet, it is still the best way to describe conditions in the ocean container shipping industry.

In the past year, we have seen a wild swing from a record-number of blank sailings in March 2020 to a post-peak season surge in volume that has reached almost unsustainable levels. As recent reporting from CNBC and others has illustrated, one of the most devastating consequences of the instability is the disruption of United States agricultural exports.

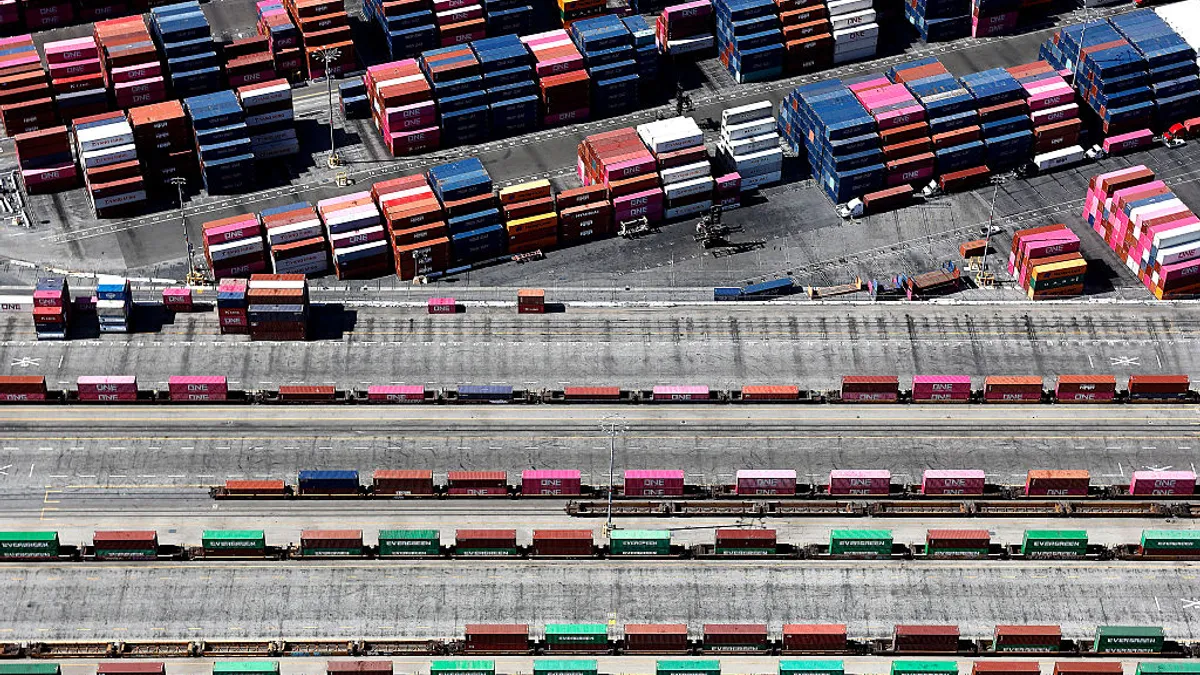

There is not a singular cause for the difficulties being felt around the world, but one of the major drivers is the congestion at ports across the globe. Ports everywhere are backed up, following factory closures and blank sailings in early 2020, a rapid rebound as consumer spending patterns recalibrated, and then logistics difficulties caused by warehouse space shortages and workforce disruptions.

Overcoming the cargo hurdle

To support better cargo fluidity around the world, but particularly for U.S. exporters, all industry participants must work together. Every participant in the supply chain must collaborate to get through this challenging time, and, as regulators, we must also work with our counterparts across the globe to find solutions.

U.S. companies are facing limited access to containers and space on vessels to ship exports abroad. Agriculture exporters, most notably those in America’s heartland, are struggling, paying high premiums that eliminate profit and the risks of loads not getting to customers on time.

Global solutions are the only way to make a difference when addressing a worldwide phenomenon.

However, U.S. exporters are not the only ones in this position. Container shortages and export difficulties are an issue across the globe. The European Shippers Council recently appealed to the European Commission for relief, Australian exporters are "taking extreme measures" to get products to market in a reasonable time, and seafood exporters in Southeast Asia are facing cost increases between 145% and 276% for exports to Europe.

Although container supply generally kept up with container port handling in 2020, containers are not where they need to be. Reporting shows containers are stuck in depots for more than 30% longer than usual, even in the places where they are needed most. As a result, carriers are willing to ship empty containers back to China, to avoid the time it takes for the containers to be refilled with exports and the downtime for exports to be unloaded and the containers refilled upon their arrival in China.

Pinpointing a solution

The most obvious answer to a container shortage is to manufacture more containers.

Most containers are made in China, so we were pleased to see the Chinese government encourage an increase in container manufacturing and investment in containers increasing. We have, however, seen some reporting that indicates this encouragement may not have been heeded, and we hope that is not the case.

Regardless, containers take time to build. And, furthermore, simply injecting more boxes into the system will not solve the problem — unless other bottlenecks are also addressed.

Unwinding the congestion at ports around the world is complicated. Every participant has a theory as to who is to blame, but the truth is that there is no one party at fault. Everyone is responsible, but no one is to blame.

If we, as a Republican and a Democrat, can cooperate on this issue in such divisive times, certainly others with diverse interests should be able to do so, as well. We, therefore, urge industry stakeholders to collaborate to find mutually beneficial solutions both for the current crisis, and to prevent something this disruptive from happening again.

We must learn from this situation and find ways to prevent similar conditions in future times of disruption.

If we, as a Republican and a Democrat, can cooperate on this issue in such divisive times, certainly others with diverse interests should be able to do so, as well.

Parochially, as a regulatory authority, the Federal Maritime Commission can contribute by increasing monitoring and enforcement with an eye toward protecting the public from those who attempt to exacerbate and profit from the current situation.

Last month, the FMC announced that Commissioner Rebecca Dye, in connection with her Fact-Finding 29 Investigation, will issue information demand orders to ocean carriers and marine terminal operators to determine if legal obligations related to detention and demurrage, container return and container availability for exporters practices are being met.

Information received from parties receiving demands may be used as a basis for hearings, FMC enforcement action or further rulemaking. In addition, the FMC can also attempt to guide, advise and bring together the various parties with their diverse interests toward the common goal of a fluid and efficient supply chain.

But one of the best ways we can help fix the problem is by collaborating with our peers in China and the European Union. Global solutions are the only way to make a difference when addressing a worldwide phenomenon. As two individual Commissioners, we look forward to working together within the FMC and with our peers around the world to find immediate and long-term solutions that work for everyone.