This is a contributed op-ed written by Kamala Raman, senior director analyst at Gartner Supply Chain Practice. Opinions are the author's own.

For years, China has been the go-to destination for low-cost, high-quality manufacturing. It has been a key source of supply for high tech, industrial, automotive, retail, pharmaceutical and other industries. But times have changed.

Today, economies have moved from being complementary to becoming competitive with each other. This is especially the case with western countries and China. Thirty-three percent of businesses have moved some sourcing and manufacturing activities out of China or plan to do so in the next two to three years.

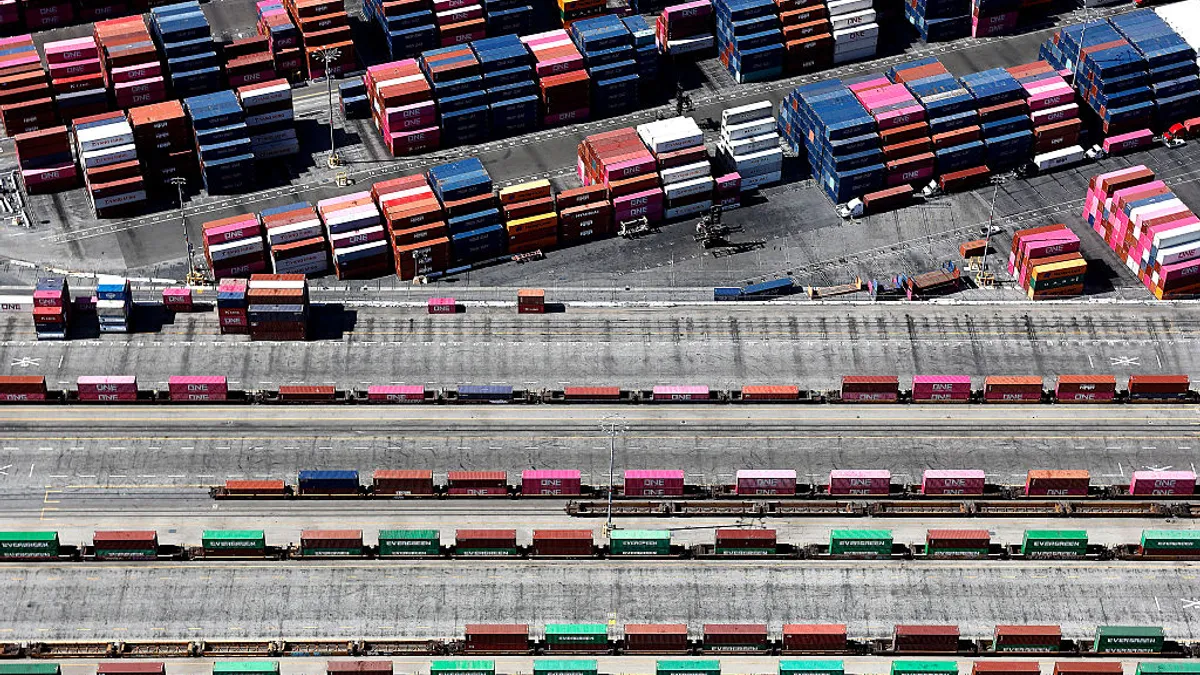

As the coronavirus pandemic expanded around the world, the fragility of global supply chains was laid bare with shortages of everything from household staples to specialized industrial components. Between the actions already taken due to the U.S.-China trade war and the inflexibility of global supply chains at a time of demand uncertainty, companies are evaluating whether they should explore diversifying their networks away from China.

This raises a couple questions. How far will companies go in their pursuit of resilience and regionalization? And how far should they?

Diversification is a spectrum

In interconnected global supply networks, every decision has ramifications that spill into other parts of the network. Multinational firms looking to improve resilience and protect themselves against a potential reshaping of global trade relations should resist reflexively decoupling global supply chains as an inevitable action.

Instead, they should evaluate the right approach for their firm using a set of factors: What is our risk appetite? How are our critical partners approaching the situation? What are we aiming to protect? What are the trade-offs? How will the financial burden be shared? Is there any kind of government incentive for moving business?

Diversifying global supply chains is often portrayed as a binary "all-or-nothing" act. It is not. Even in government contracts, only certain high-risk products might mandate all local production, including directly and indirectly sourced components, and therefore, require a true decoupling exercise.

So, if supply chain leaders go through their decision-making process, they might find that for lower-risk products it is preferable to have the product assembled locally or in a friendly country, while the sourcing locations of tier 2 components don't need to move at all.

The manufacturing process can, therefore, be split into a front end and a back end with a subassembly line in a low-cost country and the final assembly closer to home. These techniques can help remove constraints by country of origin rulings or tariffs while reducing lead time to the customer.

Companies that are greatly dependent on the sophisticated Chinese manufacturing ecosystem will have a hard time replicating this ecosystem in another country. Regionally sourcing may take significant amounts of time and money.

That's why strong market leaders will successfully address nearshore or regional sourcing by making big bets in the form of bold, market-leading capital investments. Their actions will influence key suppliers to diversify their own footprint with joint development programs or long-term contracts.

Industry coalitions, ecosystem partnerships and government-sponsored initiatives can also provide the economic scale to guarantee volumes for suppliers.

Resilience is one of many factors

Increased resilience rarely comes for free. So, any efforts in that direction must be evaluated against other critical business priorities, such as cost efficiency.

Many companies have accelerated their move out of China to other Asian countries and nearer local markets such as Eastern Europe and Mexico. While this makes sense from a geographical point of view, the sourcing and manufacturing ecosystems in these other locations are nowhere near as comprehensive as the one that has been built up in China over the last few decades, which poses a big challenge for certain industries.

For example, in the high-tech industry, the ecosystem is very clearly centered in Asia. This has been driven by a number of factors, among them state encouragement to grow these industries. The contract manufacturers that design and produce many products are concentrated in Asia, and it will require state-level support or industry consortiums to create the volumes necessary to justify significant diversification of the supply chain ecosystem.

Also, COVID-19 has shown there isn’t one ideal country or region to relocate to. A better approach is to diversify supply sources by establishing multiple sources across different regions. However, this approach can only work if it is balanced with the realities of an organization’s market position, a necessity for cost-efficiency and broader industry realities.

This story was first published in our weekly newsletter, Supply Chain Dive: Procurement. Sign up here.