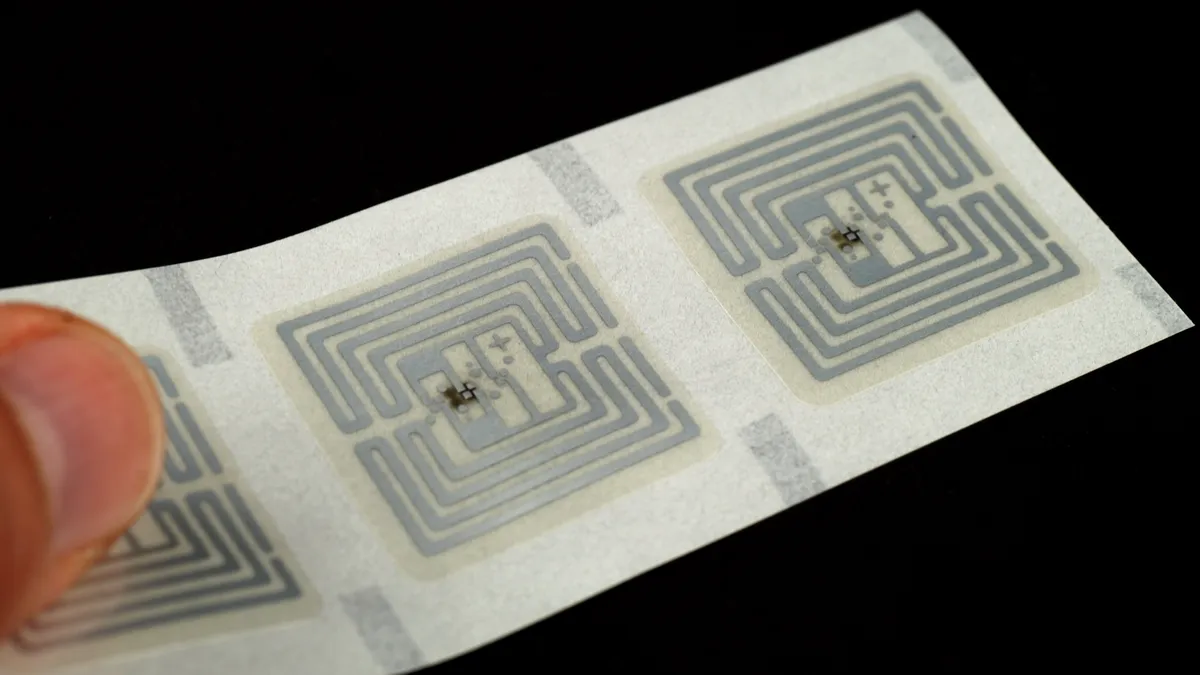

With higher accuracy rates, lower cost and the Internet of Things (IoT), RFID might finally be ready for its turn in the spotlight.

RFID — radio frequency identification — may have been ahead of its time in a flurry of high-profile pilot projects in the early 2000s that didn't seem to pan out. It's not fair to say that RFID technology went away, but it is in the midst of a comeback.

Thanks to advances in sensors and data processing technology, companies are again looking at tagging trucks, pallets, cases and items to track location and other data like temperature and impacts.

There are various use cases where RFID could be the best option for low-cost inventory tracking. But the technology still faces headwinds from competing technologies that could keep it from assuming the industry prominence its proponents have always thought it deserved.

Walmart's cautionary tale

In 2003, Walmart launched a pilot program with 100 of its top suppliers and vendors to tag all pallets and cases within two years, but by 2006, the initiative was all but dead.

A combination of poor timing on the heels of industry-wide ERP implementation and other IT investments, a lack of data-crunching capability to use the information generated from tracking tagged products and the high cost of the RFID tags, meant even Walmart couldn't scale it up

Behind-the-scenes resistance led many Walmart vendors to take a "slap and chip" approach.

"A lot of suppliers at the time told their 3PL, if we get an order from Walmart, slap an RFID chip on the pallet, but we're not going to spend a lot on the technology," Dwight Klappich, vice president of supply chain execution research for Gartner, told Supply Chain Dive.

One of the problems with the Walmart pilot was the inability of companies to turn the data generated by the tags into actionable intelligence. In 2009, Procter & Gamble ended its pilot program for certain product displays because Walmart did not act on the available information to improve store operations, Supply Chain Digest reported.

Today, the systems of record — ERPs and transportation and warehouse management systems — are able to ingest data from RFID in real time, Jason Ivy, senior manager of supply chain and logistics for Impinj, a RAIN RFID provider, told Supply Chain Dive.

"Now you can scan 100 items at a time as they pass by the RFID reader rather than scanning the barcode on each item one at a time," he said. "Whether you're tracking goods flowing through the supply chain or assets that support the supply chain, you can now have a physical record that's really meaningful and useful."

Yet under the radar, companies turned to RFID for a range of uses, like tracking medical devices in hospitals and trailers in trucking terminals. Once a victim of the hype cycle, RFID has quietly repositioned as a technology now ready for prime time.

"There are places where RFID brings unique capabilities that you can't do with barcode, for example, any type of asset tracking," Klappich said. "The key use cases are all about location transparency."

The retail sector has been one of the largest adopters since the Walmart trials. Macy's, for example, is tagging individual apparel items for 900 retail locations and boasts an accuracy rate of 97%. Early results showed Macy's improved key measurements like inventory variances, markdowns and order fulfillment.

Falling costs for the technology is one of the reasons apparel companies can tag thousands of items. At the time of the Walmart program, tags cost 35 to 40 cents apiece, and the price has dropped to about 5 cents apiece, Ivy said.

Apparel companies are moving to source tagging, in which items receive RFID at the manufacturer so they can be tracked from factory to store shelf.

RFID use cases focus on its strengths

Accuracy for the RFID tags has improved over the years. In a recent study from GS1 US and Auburn University's RFID Lab, researchers found nearly 100% order accuracy is possible in the retail supply chain. The study found older systems like barcodes could be inaccurate on up to 69% of orders compared to less than 0.01% with RFID data. With higher data accuracy, retailers can effectively eliminate cost claims and chargebacks, justifying the investment in the technology, the study said.

Now RFID has to compete with other solutions such as Bluetooth tags or other sensors that accomplish much of the same mission but use different technologies.

One difference to consider is that most RFID tags don't use batteries, so they're better for tagging items in what's called an open-loop system, in which the objects move one way through the supply chain. Assets that return to base, such as truck trailers or plastic totes, operate in a closed loop system and may be more suitable for systems that use batteries.

With the ability to store and transmit data, RFID could be a natural fit to enter data into supply chain blockchain applications.

"You can start thinking about what information you need on the RFID tag beyond the SKU number and whether you should use RFID or maybe use a 2D barcode instead to support the blockchain," Klappich said.

Using RFID data in the blockchain will help take the human factor out of the equation, reducing barcoding errors.

"The real power behind blockchain will be when you can physically track the item in the supply chain," Ivy said. "There's a place for RFID in managing the flow of data as well as the goods in the supply chain."

The combination of RFID and blockchain could improve visibility for shipments at the dock door.

"When the shipment enters the truck you're making a financial transaction, and the chain of custody can follow the 3PL or another party in the supply chain, and the blockchain can issue the transaction in the ledger right at that point," Ivy said. "It's the last place you can get it right, especially for outbound shipments."

The dark supply chain could be the next step

The higher accuracy rates for RFID could also play a role in developing "lights out" manufacturing and logistics that don't require human involvement, Ivy noted. RFID can track items in real-time without passing in front of a scanner one at a time like items with barcodes.

"This connection to the physical items is key in the process to moving to lights-out operations," he said.

Despite overcoming some of the barriers like cost and accuracy that slowed adoption, RFID technology is still fighting for a role in the supply chain. However, some questions remain about how RFID competes with other solutions in the market such as barcodes and Bluetooth tags.

"Back in 2004, we thought this was a technology looking for a problem, and now we have problems looking for technology," Klappich said. "You have to take a step back and look at your challenges and not let the technology itself dictate what you do but let the use case dictate the right technology."

This story was first published in our weekly newsletter, Supply Chain Dive: Operations. Sign up here.