Editor's note: This story is part of a series marking Supply Chain Dive's five-year anniversary. Look back at some of the most important stories in supply chain since 2016 in this round-up.

FedEx's globe-spanning air cargo network looks much different than it did five years ago. It has added dozens of aircraft to its fleet, expanded major shipping hubs and cut down on emissions — although it fell short of a goal set a few years earlier.

In 2011, FedEx sought to reduce aircraft emissions 30% by 2020, from a 2005 baseline. The cargo airline aimed to reach this target, revised from a 20% reduction goal announced in 2008, in part by replacing aging aircraft and using more sustainable fuels.

But as the decade progressed, FedEx's e-commerce volume ballooned. Older, less efficient aircraft stayed in service to keep pace with demand, the company said in its 2021 ESG report. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated this trend, leading FedEx to fall short of its goal. The company ended up reducing its aircraft emissions 27% from 2005 levels.

The fuel burned by FedEx and other air cargo carriers' jets remains a substantial roadblock toward reaching their — and customers' — ambitious sustainability goals.

"Unlike other transport activities that can be powered by batteries or already have wide availability of low-carbon fuels, achieving 'true' sustainability in aviation is an intractable problem," said FedEx Chief Sustainability Officer Mitch Jackson in an email.

FedEx is among many airlines that have made progress in reducing their energy intensity, but aviation remains a notable source of global emissions. Aviation produced 2.8% of global CO2 emissions in 2019, according to the International Energy Agency. And an Environmental and Energy Study Institute report said airfreight generated 19% of aviation's emissions the year before.

Aviation emissions will see slight decline by 2030

Aviation "is one of the most difficult sectors to decarbonise" as it requires high-power output and energy-dense fuels, according to the IEA. The agency projects emissions from passenger and freight vehicles will see larger emissions declines by 2030 compared to aviation emissions.

Roei Ganzarski, executive chairman of electric aircraft maker Eviation, said the technology for making large freighter aircraft like the Boeing 777 all-electric will be available, at the earliest, 30 years in the future.

"Even if we could create a propulsion system that was big enough, powerful enough, lightweight enough to go on that size aircraft, right now and in the foreseeable future there's no energy storage system that could even come close to competing with Jet A fuel," Ganzarski said.

Shippers want lower emissions, but need more airplanes

Companies are taking notice of aviation's emissions challenges as they lay out their own sustainability goals. L'Oreal found reducing its reliance on airfreight by shifting more volume to rail and sea would have an outsized impact on its supply chain emissions.

"I think what we'll see in the future is … airlines that make those changes to reduce those emissions faster than everybody else will be utilized more and will grow faster," said Greg Bollefer, executive vice president of commercial and product development at freight forwarder Green Worldwide Shipping.

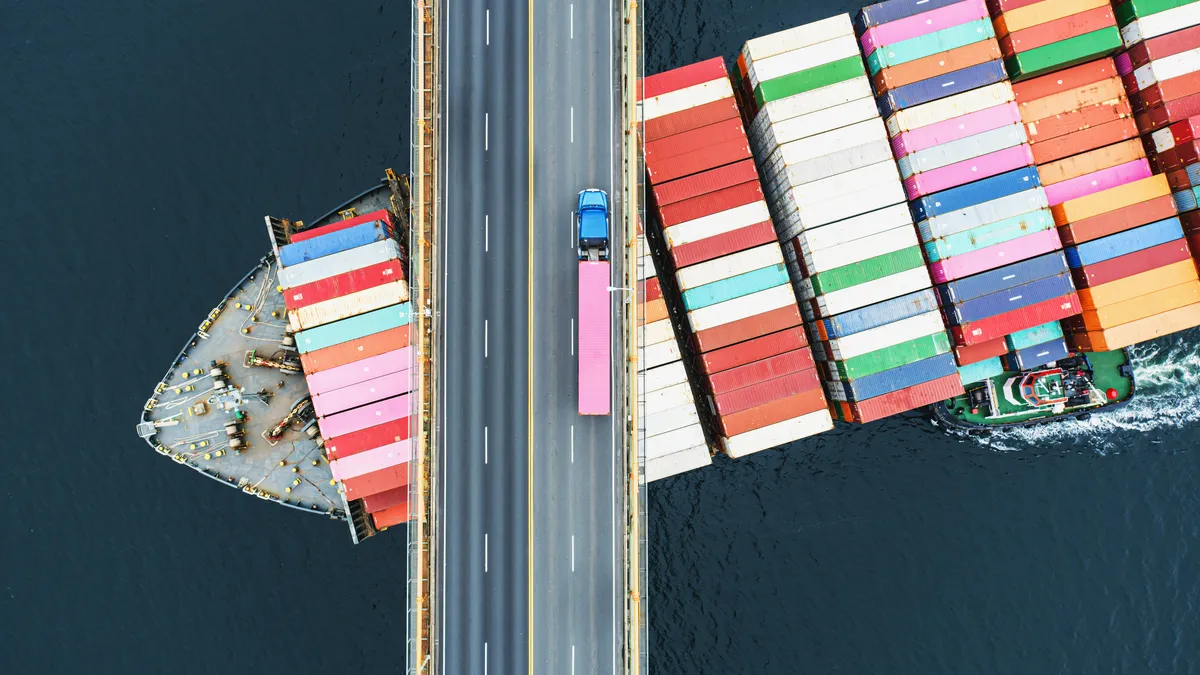

Glyn Hughes, director general of The International Air Cargo Association, agrees. He noted many shippers are now reporting how much their supply chains produce in emissions, and they're looking for carbon-neutral transportation options. In the long-term, TIACA supports manufacturers having "a blended series of supply chains" that use ocean shipping as well to reduce environmental impacts.

"Unlike other transport activities that can be powered by batteries or already have wide availability of low-carbon fuels, achieving 'true' sustainability in aviation is an intractable problem."

Mitch Jackson

FedEx Chief Sustainability Officer

"We would support that because we think it's much better to have a globally efficient economy that has the least environmental impact and the maximum benefit for society," Hughes said.

But the COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the importance of air transport in supply chains. Speed, not cost, was the priority as companies transported personal protective equipment from China to the U.S. for use by frontline health care workers. Air transport also plays a key role in e-commerce delivery, with online retail giant Amazon using its Air network to replenish its warehouses. Some companies have relied more on air transport this year to avoid a congested ocean freight environment.

Those needs are helping overall air cargo demand grow, even if some companies are reducing their reliance on the transport mode. Seventy-two percent of airline CFOs and heads of cargo surveyed by the International Air Transport Association in July expected cargo demand would increase in a year, aided by growth in passenger flight activity. That's an improvement from the previous survey's result in April of 56%.

Airfreight isn't exclusive to all-cargo carriers, with IATA estimating 50% of cargo volumes fly in the belly of passenger aircraft. Transporting passengers brings its own sustainability challenges: Passenger operations contributed to around 85% of the industry's emissions in 2019, while dedicated freighter and belly cargo operations each contributed around 7%, according to the International Council on Clean Transportation.

Sustainable aviation fuel has short supply, high cost

Like FedEx, UPS has seen its demand spike during the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to more flights. The majority of UPS' CO2 emissions (61.3%) come from airline fuel, and the amount emitted from its air fleet increased 12% from 2019 to 2020, according to its Global Reporting Initiative report. UPS aims to increase its use of sustainable aviation fuels, which it called "the only decarbonization path for the aviation sector," to reduce emissions from its air fleet.

Sustainable aviation fuels, known in the industry as SAFs, use an alternative feedstock to crude oil, such as cooking oils, plant oils or municipal waste, according to the IATA. FedEx is eager to use more SAFs, Jackson said, "but there's not nearly enough supply currently available. Plus, the limited supply that is available costs at least three times as much as conventional jet fuel."

Like the all-cargo carriers, passenger airlines are keeping sustainability in mind by using newer, more fuel-efficient aircraft and exploring uses of SAFs, Airlines for America said earlier this year.

Jackson said the Sustainable Skies Act, which was introduced into Congress in May, would encourage additional SAF production via a tax credit for producers. House and Senate versions of the bill remain in their introductory phases.

There's currently "no choice" to substantially reduce large aircraft emissions outside of SAFs, Ganzarski said. Smaller, feeder aircraft used in carriers' shorter flights, however, are already on the path to electrification. DHL Express announced in August it ordered 12 all-electric Alice aircraft from Eviation for regional routes in the U.S.

"It's really a complement to the current fleet, not a replacement of it currently, unless you're a small operator whose fleet happens to be Cessna Caravans, then yes, it's a replacement," Ganzarski said. "But if you're talking about the major airlines, it's a complement."

Ganzarski said in the future, larger aircraft — "maximum 100 seats" and similar in size to the ATR 72 turboprop airliner — will be able to be supported by electric power. Additionally, flight ranges should improve as batteries do.

"If you look at how our cell phone batteries have evolved in the last few years, I think that the investment in different battery technology means that [electric aircraft] will start small and short distance," Hughes said. "Probably within a 10-year timeframe, we're talking about significantly longer ranges with significantly larger payloads."

With aviation's fuel challenges not going away any time soon, Bollefer said LCL express services are popular for shippers looking to reduce the costs and emissions that come with air transport while still keeping transit times brisk.

Sourcing products closer to the end user is another way for companies to reduce their carbon footprints if their operations allow, he added.

"If something's sourced in China that can be sourced in Mexico for the same price, but you lower your overall CO2 emissions by 10,000 tons, that's a huge impact," Bollefer said.

Clarification: A previous version of this article did not include the full name of Green Worldwide Shipping.