This article is part of a series on the impacts climate change and severe weather have on supply chains. View the entire series here.

The COVID-19 pandemic took center stage for supply chains in 2020, but it was far from the only risk event.

Last year set a record of 22 weather and climate disaster events, each costing at least $1 billion, according to the National Centers for Environmental Information. The previous record for billion-dollar events in a year was 16, in 2017 and 2011. The costs of 22 events of 2020 combined exceeded $96 billion in damages.

The combination of frequent natural disasters and the pandemic magnified the disruptions to supply chains, said Jon Davis, chief meteorologist at Everstream Analytics.

"You had all these storms and all these weather events last year, then you had an underlined base state of COVID," Davis said. "It just multiplies the impact of all of those things."

Costly natural disasters become more frequent

Supply chains and transport networks are no strangers to dealing with storms. The companies in these industries are known for repositioning inventory and aiding with disaster relief.

"Every time, our industry bands together to safely and efficiently deliver food, water and other emergency supplies and equipment to those who need them most," Ford Boswell, senior advisor at the Alabama Trucking Association, said in an email. "We've seen this in the aftermath of hurricanes, tornadoes, flooding — and even with something unusual, such as the recent Colonial Pipeline shutdown when tank haulers were used to take up the slack and move fuel supplies quickly."

But the growing intensity of natural disasters as the planet warms increases the risks logistics networks face. And the very real threat of more frequent and severe storms will require transport and supply chain managers to take lessons learned from past disasters and incorporate them into future risk and contingency plans.

Supply chain professionals need to take the long-term view of risk as they expand networks or routes into areas prone to storms, said Katherine Klosowski, vice president and manager of natural hazards at FM Global.

"The severe weather events may be inevitable, but the damage doesn't have to be," Klosowski said.

Wildfires

More than 10 million acres burned during 2020's record-breaking wildfire season and 46 people lost their lives.

The fires spread across California, Oregon and Washington, while Colorado also had what NOAA called a "severe wildfire season." Five of the six largest wildfires on record in California burned in August and September of last year. One of the fires, known as the August Complex, began as 37 separate fires, sparked by lightning strikes across the northern part of the state.

The Western wildfires were among the costliest natural disasters in 2020, as calculated by NOAA. The wildfire costs totaled $16.6 billion, second only to the costliest disaster of Hurricane Laura. The costs include damage to homes, businesses, agriculture and infrastructure, as well as the costs related to disaster response.

Climate change plays a part in the frequency and intensity of wildfires, according to NOAA. The planet's warming temperatures increase the risk of drought and therefore lengthen wildfire season in the western states. In fact, a drought and heatwave was another billion-dollar disaster last year and preceded many of autumn's wildfires.

Fires pose a hurdle to logistics and can stall freight movement, via truck if roads are closed and also on rail lines.

One of the challenges with fires, unlike hurricanes — there's not always advanced warning of the wildfires spreading. That puts supply chains and transport firms in a reactive, instead of proactive, position.

Still, supply chains can plan generally for fire season, which is typically in late summer and fall. Some companies have business continuity plans, while others prepare with annual drills, to ensure they are ready in case a fire spreads to their neck of the woods.

Relief organizations have responded to the need for aid and supplies during the natural disasters. The Red Cross moved disaster supplies from a location near Las Vegas to a warehouse in Western Sacramento for faster transport of supplies.

"It will greatly reduce the time it takes to get much-needed items like cots, blankets and toiletries in the hands of disaster evacuees," California Gold Country Region Chief Executive Gary Strong said in a statement.

Tornadoes

Tornadoes, unlike hurricanes, are often difficult to predict and forecast days or weeks in advance. That makes the logistics planning challenging, as there is little notice to reposition supplies.

Davis advised looking at conditions that are "favorable for severe weather outbreaks."

Often, that's the convergence of warm moist air near the ground, cooler dry air higher up and a wind shear that changes speed or direction, creating a spinning current.

"In some of the severe weather outbreaks we've had this spring, there [were] indications five or seven days in advance that the atmospheric setup would be there for a large scale, severe weather outbreak," Davis said.

Supply chains can't necessarily plan every detail, but they can begin planning about a week in advance, such as moving shipments ahead of a possible storm.

They can update strategies to reduce natural disaster risks in their networks, said Mary Long, managing director of the Global Supply Chain Institute's Supply Chain Forum at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville's Haslam College of Business.

She also advised supply chains work on bridging strategies. "How can they engage locally in high risk areas to establish partnerships during times of crisis?" Long wrote in an email.

Three separate billion-dollar tornado events occurred in the U.S. last year.

Southeast Tornadoes, Jan. 10-12

This line of storms included more than 80 tornadoes, causing damage in Southern and Gulf states and leaving 10 dead. NOAA estimates the cost at $1.2 billion.

"You had over a thousand reports of damage due to winds," Davis said. The high wind speeds caused power outages and downed trees on rail lines and interstates, according to Davis.

The January storms were somewhat unusual, given that tornadoes are much more common in the spring and summer.

"Weather is unpredictable, and dangerous storms can happen anytime," Boswell said.

Tennessee Tornadoes, March 2-4

The tornadoes sweeping across Tennessee were categorized as F3 and F4, which indicates winds between 158 mph and 260 mph. Twenty-five lives were lost; damage totaled $2.4 billion.

Ceva Logistics' technology distribution campus, located outside Nashville, was affected by the storms.

"The destruction was intense and widespread with two of the campus' five buildings destroyed, two sustained heavy damage, and one structure remained relatively unharmed," Ceva said.

The company activated contingency plans right away and was able to resume full operations three weeks later.

Southeast and Eastern Tornadoes, April 12-13

April's line of storms had at least 140 tornadoes, according to NOAA, while Davis estimated the outbreak closer to 200 tornadoes.

The storms spread as far southwest as Texas and northeast as Maryland. Three were F4s. Damage totaled $3.5 billion and 35 people died.

The regions where tornadoes rolled through are home to several manufacturing plants.

A tornado on April 13 struck a BorgWarner plant in Seneca, South Carolina. The manufacturer is among the largest automotive suppliers, with customers including Ford, Volkswagen and GM. It took about two weeks for full production to resume.

Severe weather

When a thunderstorm is far-ranging and produces other types of weather events, such as hail, high winds or even tornadoes, NOAA may categorize it as "severe weather."

In 2020, eight billion-dollar severe-weather events cost an estimated total of $22.6 billion. But one storm, lasting just 14 hours, is responsible for nearly half that amount.

On Aug. 10, 2020, a derecho traveled 770 miles, from southeast South Dakota to Ohio, causing damage NOAA said was comparable to the impacts of a hurricane. It cost an estimated $11.2 billion and caused four deaths.

Derechos are fast-moving bands of thunderstorms, with hurricane- or tornado-force winds that follow straight lines.

"These were hurricane-type winds in the middle of the Midwest corn belt, in and of itself a unique situation," said Davis. It severely impacted corn producers. "Any company or procurement individuals that are buying corn, maybe feeding animals, or making things with corn, this was certainly a big issue for them."

There are also numerous ethanol plants in affected areas of Iowa and Illinois, many of which were shutdown for days or even weeks. "This in turn created a whole problem with ethanol and getting that corn-based ethanol into the supply chain," Davis said.

Winds were so strong, "numerous semi trucks were also blown off of major highways," NOAA said. The strongest winds were between the Highway 30 and Interstate 80 corridor, the agency said, including in the Des Moines, Iowa, metro area.

There wasn't much supply chains could do to ready for the derecho; it was unprecedented. But businesses can take a lesson learned and fortify their facilities against another such storm.

"Protecting a supply chain against derecho damage means protecting the facility against windstorm damage," Klosowski said. "Maintaining a building envelope allows the business to continue operations; this is accomplished through roof securement, skylight securement, and ensuring roof-mounted equipment will not tumble."

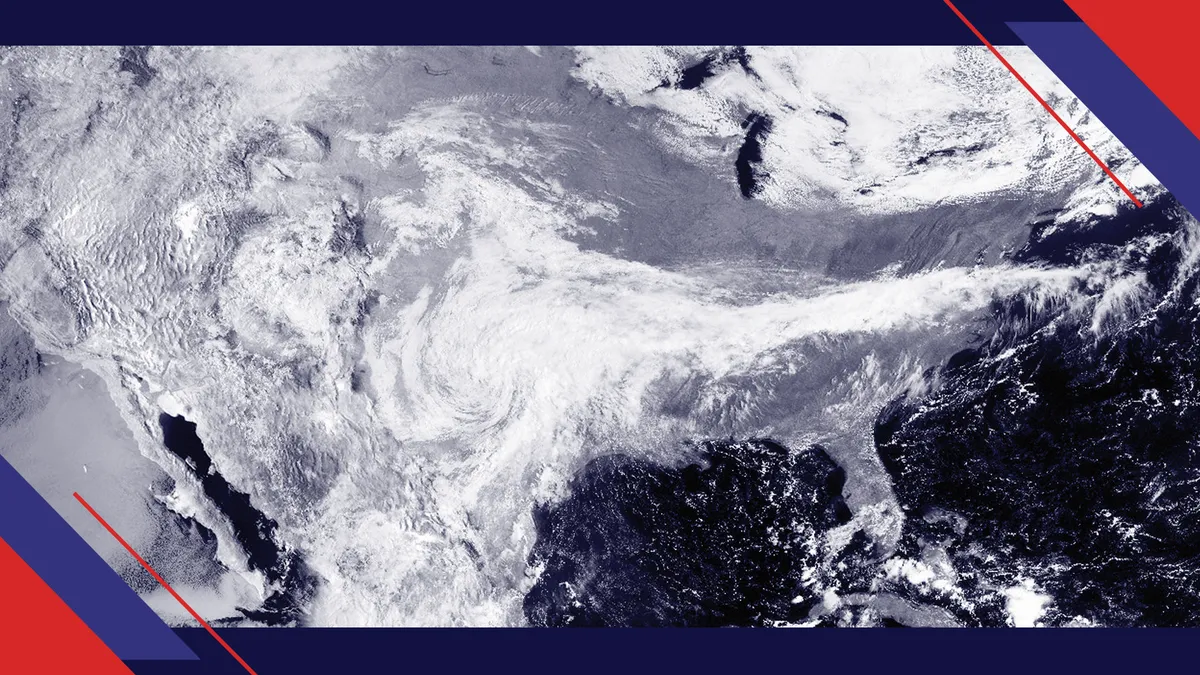

Hurricanes

The 2020 Atlantic hurricane season had a record-breaking 30 named storms and 12 storms that made landfall in the U.S., NOAA said. Seven of them caused more than $1 billion in damage each.

By NOAA's account, two weather systems produced a historic amount of damage: Hurricane Laura and Hurricane Sally.

Hurricane Laura

Hurricane Laura's winds were clocked at up to 150 mph, and storm surge topped 15 feet. Hundreds of thousands of customers were left without power in Louisiana and Texas.

When the damage was done, the cost was an estimated $19.2 billion, and the hurricane killed 42 people. But some catastrophe was mitigated, as logistics networks had almost a week to prepare for the storm.

Spot TL volume jumped in preparation for what ended up being a Category 4 hurricane that made landfall in Cameron Parish, Louisiana, on Aug. 27. Ports paused operations, authorities implemented a significant closure on Interstate 10 in Louisiana, and mandatory evacuations ahead of the storm restricted FedEx, UPS and Postal Service operations in dozens of ZIP codes.

Supply Chain Dive sister publication Transport Dive reported that logistics and trucking companies worked together to position assets and freight in advance, which included moving water and medical supplies to the safest warehouses for later use.

Hurricane Sally

As areas across the Gulf Coast recovered from Hurricane Laura, Hurricane Sally hit. But this time, it was a dangerously slow-moving, Category 2 hurricane that made landfall in Gulf Shores, Alabama, on Sept. 15.

Wind gusts got up to 100 mph, and there was up to 30 inches of rainfall. The event cost $7.3 billion and caused five deaths.

The ports of Mobile and New Orleans closed in advance. Norfolk Southern ceased operations at the Port of Mobile, and told customers at the Port of New Orleans to expect delays of up to 72 hours.

UPS suspended service in parts of Alabama, Florida, Louisiana and Mississippi, while FedEx did the same in parts of Louisiana, and the Postal Service paused in Alabama and Louisiana.

"Interstate 10, one of the major East and West corridors in the Southern West, was closed," Davis said. "To prepare we were able to get this timing and predicted info to customers, who then increased their amount of shipments using I-10 in advance of the storm. Once Sally moved in, I-10 was closed but many customers had already made up the difference in advance — mitigating the potential impacts."