Dan Pashman wanted to create his own pasta shape. After years of dreaming that he’d be the guy to add a new kind of pasta to your grocery store’s selection, and then reporting on the quest through his podcast "The Sporkful," he was ready to launch cascatelli (from the Italian word for waterfall, which the pasta shape resembles) into the world last year.

Then he ran into the COVID-19 pandemic.

"Like many people, I’m accustomed to clicking a couple of buttons on my phone or computer and a package shows up on my doorstep in a few days," said Pashman, who had no previous food development experience. "I never thought about how many months of preparation and planning and movement of materials had to take place for that to happen."

Pashman’s "Mission ImPASTAble," the multi-part podcast series about making Cascatelli by Sporkful, encapsulates the supply chain hurdles businesses and manufacturers have faced since March of last year. From not being able to find raw materials to make necessary manufacturing parts, to having trouble sourcing paper for boxes in a more ecommerce-heavy world, cascatelli has taken a bumpy road to get from Pashman’s brain to your plate.

Innovating to work around material shortages

Pashman and his team hit their first roadblock in March 2020. He partnered with D. Maldari & Sons to make the pasta die, which is used to give the pasta its shape. But most bronze (used to make the die) comes from Italy and the Middle East, said Pashman, areas that were both hard hit by COVID-19 early. Foundries were only running with skeleton crews.

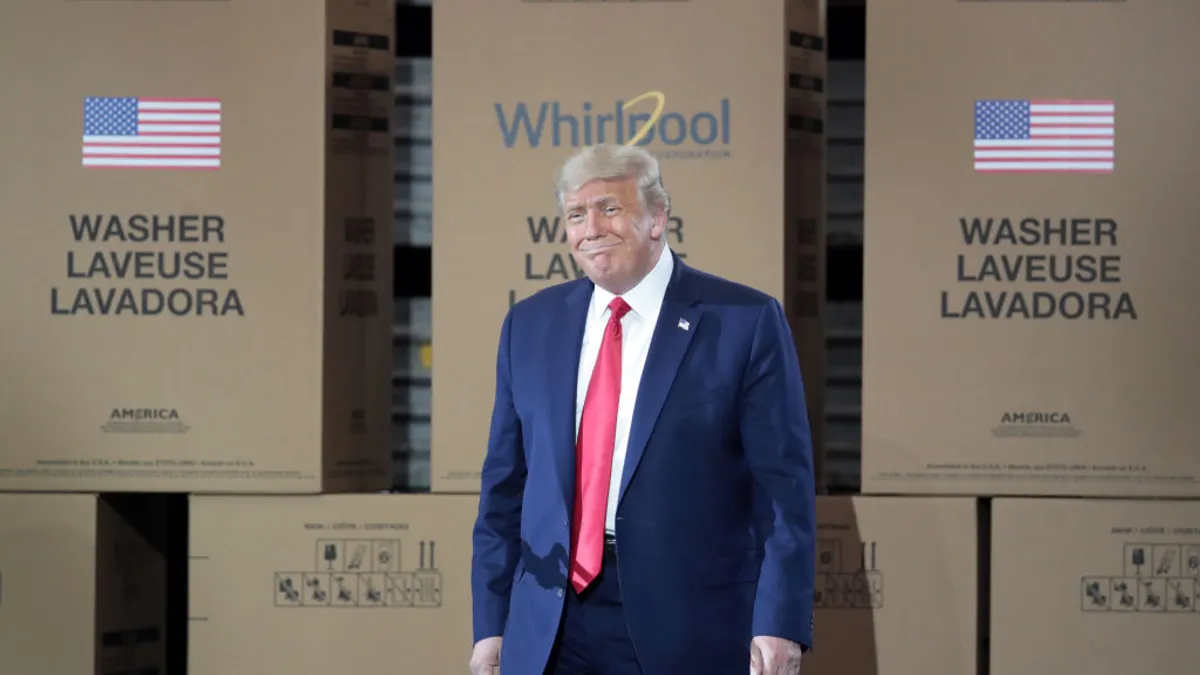

For dies that could still be made, Pashman wasn’t a priority customer. Because of a sudden demand for dried pasta at the start of the pandemic, pasta companies upped their production by 30%, according to Slate. Established companies came first, not one guy with a podcast trying to make a life-long dream come true — even if he does have a James Beard Award.

Raw materials for dies usually took three to four weeks to get, but they were now taking "more like three to four months," Pashman said.

So Pashman got creative: He found an old die that wasn’t used anymore. D. Maldari & Sons took out the inserts that made another pasta shape, and popped cascatelli’s in.

That kind of supply chain innovation has kept companies going during the last 18 months, said Jonathan Eaton, national supply chain practice leader at Grant Thornton. Supply chain disruptions were "at an all-time high" due to events like new tariffs, Brexit, the Texas winter storms and cybersecurity attacks that shut down an oil pipeline and meat processing facilities.

Businesses can’t always immediately overcome hurdles like lack of capacity, labor or raw materials. But they can use an old die to make a new one. "People are absolutely looking at innovative ways to overcome [things like] that," Eaton said.

Boxed in by boxes

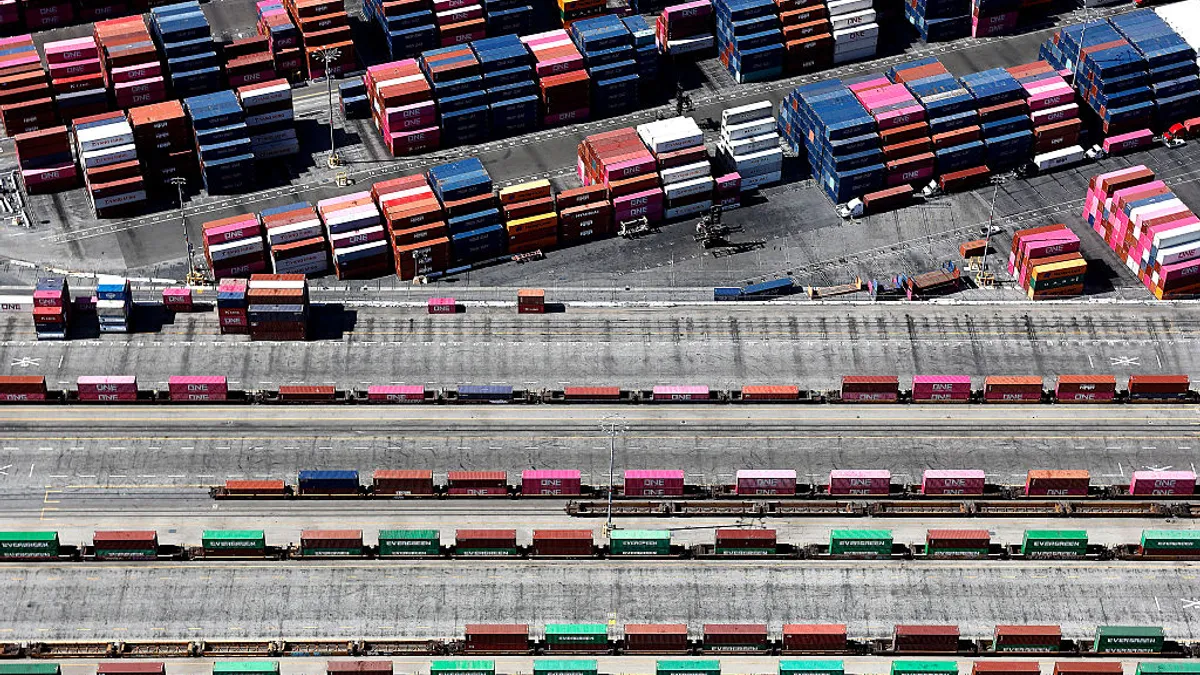

Once the team (which included pasta maker Sfoglini Pasta) had the shape and sourced the right flour, they ran into another supply chain problem: finding paper to make boxes. The sudden rise in demand for online shopping had caused demand for corrugated cardboard to spike.

Originally, Pashman wanted to make 5,000 16 oz. boxes of cascatelli, to ship directly to consumers from the Sfoglini Pasta website. Because Sfoglini couldn’t source enough material for boxes, they only made 3,700.

The pasta went for sale on the Sfoglini Pasta website on March 19, 2021. The whole 3,700-box run sold out in less than two hours. Then the story went viral, with cascatelli appearing everywhere from The New York Times to Access Hollywood to Sarah Jessica Parker’s Instagram feed. Orders kept pouring in.

To overcome the box issue, the team first made a few five pound bundles that they packaged in plastic and affixed with a label. That worked in a pinch, but those bags still had to be packaged by hand so it was not a good solution in the long term, said Pashman.

Instead of continuing to wait for that specific paper product, which made a "rougher, recycled paper" look, Pashman said they switched to a different kind of paper that was easier to source. The newer boxes are shinier because of it.

The late March blockage of the Suez Canal didn’t help either, even though their order was coming from an American supplier. Just like with the original pasta die, Pashman and his small project was pushed to the back of the shipping line.

"Other companies waiting for paper orders overseas … called up willing to spend more money and make bigger orders," said Pashman.

Pashman could have overcome such future hurdles by partnering with a co-packer or distributor, said Eaton. Those partners have the infrastructure and relationships to help buffer supply chain disruptions, and get products onto grocery store shelves.

But Pashman decided to stick with Sfoglini and D. Maldari & Sons. They’re currently focused on building up inventory to fill back orders (wait times for online orders is 12 weeks) and prepare for their first grocery store launch, in Fresh Market grocery stores in October, as well as in some restaurants.

Some complications wouldn’t have been a bad thing for the podcast, said Pashman, "because, from a storytelling perspective, you need drama and tension and there has to be struggle, otherwise it’s not an interesting story," he said.

But even he had his limits. "It all worked out in the end, and I learned a lot doing it," he added, including a new appreciation for the power, and hamstrings, of supply chains.

This story was first published in our weekly newsletter, Supply Chain Dive: Operations. Sign up here.