The conversation changed in February.

The risk sourcing from China presented to supply chains no longer centered around the trade war and tariffs as it had for the past two years.

Rather, the cloud of COVID-19 began to cast a dark shadow on global supply chains. The illness, caused by a novel coronavirus, originated in Wuhan, China, and quickly spread within and beyond the country's borders. Thousands fell ill, employees stayed home from work and quarantine measures took effect. Production slowed in China, which sent buyers scrambling to find alternative suppliers to keep product in their warehouses and on shelves.

The global pandemic highlighted an issue with supply chains as businesses embraced globalization and sought low-cost labor sources.

"We're too dependent on China alone," Steve Bowen, CEO of Maine Pointe, a global supply chain and operations consultancy, told Supply Chain Dive.

That viewpoint began to emerge years before COVID-19, gaining steam as the U.S. imposed tariffs on more than $300 billion of imports from China.

The trade war prompted many firms to diversify their supply chains outside of the country. Still, manufacturing industries and supply chains have deep roots in there, which makes it challenging for businesses to leave when risks, such as tariffs or a viral outbreak, come along.

The magnitude of shock to global supply chains has been far greater from the COVID-19 pandemic than the U.S.-China trade war. Yet understanding the effect the viral outbreak had on global supply chains cannot be done in a vacuum.

Tariffs on Chinese imports, still in place today, have made it more costly in the current crisis for importers to obtain much-needed medical supplies.

At the same time, the tariff battle laid the foundation for assessing upstream risk in China. The U.S.-China trade war created such an immense amount of volatility in a short period of time that it "heightened the awareness that supply chains had to have on risk mitigation," Jeff Pratt, supply chain leader at BDO, told Supply Chain Dive. Businesses that recognized risk in China before the pandemic were in a better position to weather the storm, as they had already begun the work of diversifying suppliers, experts told Supply Chain Dive.

Past: The US-China trade war

Supply chains diversify outside China

U.S. importers and associations for years have feared the risks China sourcing could have on their supply chains, from human rights violations to intellectual property concerns — one of the bases behind the U.S. imposition of tariffs on China under Section 301 and a cornerstone of the phase one trade agreement between the two nations.

Manufacturing wages rose as industries flourished in China, negating some of the low-cost sourcing benefits for importers, Virginia Haufler, associate professor in the Department of Government and Politics at the University of Maryland, told Supply Chain Dive.

Reorganization of supply chains "was always going to happen anyway," she said. The tariffs on hundreds of billions of dollars worth of goods trade between the U.S. and China "just made it happen faster."

A 10% tariff on $250 billion worth of imports from China got the attention of the procurement team at RF IDeas, a manufacturer of card readers.

But it wasn’t urgent enough to take action, said Lee Smith, senior buyer at the company, as suppliers absorbed some of the tariffs into their margins.

"When it went to 25%, we decided we had to do something," Smith told Supply Chain Dive. "That’s when we started really looking around to see what else we could find."

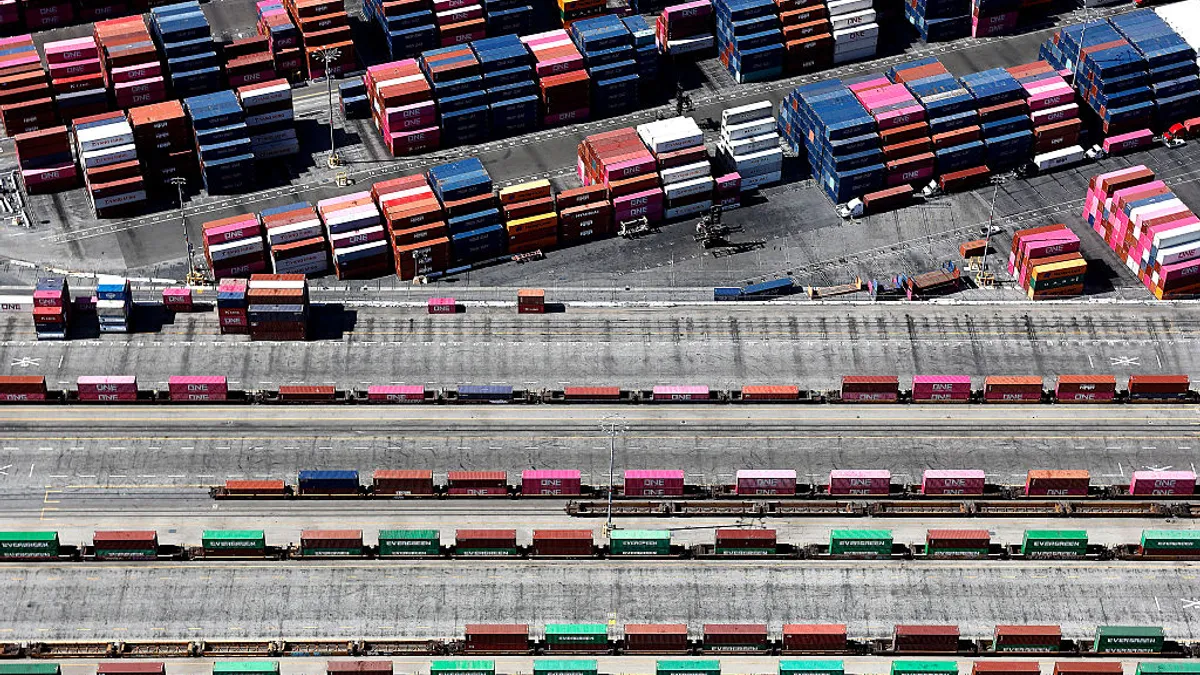

RF IDeas didn’t leave China, and doesn’t intend to in the future, because in many cases costs for finished goods are still lower in China, even with tariffs in place. But the company sought out additional suppliers in locations such as Mexico, Vietnam and Taiwan to avoid the tariffs on component parts and reduce costs. Corporate earnings calls reveal it wasn’t alone in such a strategy. Williams-Sonoma in summer 2019 laid out plans to halve the amount it sources from China. More than 80% of fashion brands in a July U.S. Fashion Industry Association report said they planned to reduce sourcing from China.

"Southeast Asia has emerged as a manufacturing hot spot," a Boston Consulting Group report from February said. Exports surged from Cambodia, Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam.

Mexico also emerged as a sought after alternative, especially with the passage of the United States-Mexico-Canada agreement and continued open trade flows across borders.

Smith said his firm found an added benefit working with a manufacturer in Mexico: shorter lead times. With China sourcing, RF IDeas needed to account for four to six weeks to manufacture and an additional four to six weeks to ship by ocean freight. "We have less control there," he said.

A Foley & Lardner report surveyed 160 U.S.-based executives across industries and found two-thirds have moved, plan to move or are considering moving some of their operations to Mexico, citing global trade tensions. The survey took place in December 2019, in the early stages of the COVID-19 outbreak, and before disruptions to global supply chains became evident.

"We've seen that as a strategy in general since the tariffs of last year," Randy Ofiara, VP of enterprise sales at BlueGrace Logistics, told Supply Chain Dive, referring to diversified sourcing.

But even as importers add tier one suppliers in countries other than China, those suppliers may still rely on China for raw materials or intermediate inputs. Vietnam imports up to 60% of its raw materials in the garment industry from China.

"The U.S. is still importing things from China. It's just through other countries," Haufler said, meaning supply chains with diversified tier one suppliers are not necessarily immune to the risks in China.

Present: The COVID-19 pandemic

Trade war lays the foundation to weather the pandemic

RF IDeas began to see an impact to its supply chain in early February as the result of the outbreak, including some delivery delays on inbound supplies. But Smith said supplier relationships are strong and buyers and vendors have remained in touch frequently.

"I think the trade war helped us be more prepared for the virus," Smith said. His company has several suppliers and alternate sources, because of the work the firm did to diversify during the height of the trade war. "We are getting by OK for the most part," he said in late March.

"It has opened our eyes to the potential in other countries — that there are other suppliers out there."

Lee Smith

Senior Buyer, RF IDeas

Executives on earnings calls have acknowledged the global pandemic situation as dynamic and disruptive but expressed some confidence about their ability to weather the storm with a diversified supply chain.

"As we worked through the tariff situation, we found ourselves in a pretty good place there, because our sourcing organization has worked over the last decade to diversify away from China," J.C. Penney CEO Jill Soltau said on a February earnings call. "So, that’s been a little bit of comfort" as the retailer monitors coronavirus spread and impact.

Ralph Lauren President and CEO Patrice Louvet described the COVID-19 outbreak as a "highly dynamic situation" on a February earnings call. But he added, the company has worked over the last one to two years to diversify its supply chain. "We’re less dependent on one market," Louvet said. "We have a greater ability to leverage a footprint that's much broader."

And Levi's reduced its manufacturing in China from 16% in 2017 to between 1% and 2% in 2019, which CEO Chip Bergh said helped shield the brand from some coronavirus-related disruption.

Still, executives and experts emphasized the novel coronavirus and near-global shutdown is an incredibly dynamic situation — of a magnitude that no business could entirely prepare for or foresee.

Health supply chains face a double whammy

Like many industries, medical device and pharmaceutical supply chains rely on China for imports of finished goods, components and input materials. Medical equipment imports to the U.S. from China totaled $5.2 billion in 2019, and 80% of active pharmaceutical ingredients are produced abroad, primarily in China and India.

The reliance on foreign sourcing for medical supplies has squeezed U.S. healthcare supply chains and created concerns about stock levels.

Adding fuel to the fire, imports of several health products from China face tariffs of up to 25%. The U.S. granted temporary exemptions until Sept. 1, 2020 on a number of medical supplies imported from China, but they cover "only a handful of urgently needed products," Chad P. Brown, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, wrote in an analysis.

The Trump administration has expressed an unwillingness to waive the China tariffs altogether, despite pleas from industry groups to help U.S. businesses survive the inevitable economic downturn from the pandemic.

"The U.S. is still importing things from China. It's just through other countries."

Virginia Haufler

Associate Professor, University of Maryland

Responding to the immediate need for medical supplies, U.S.-based automakers said they'll retool production lines to make ventilators in the U.S.

But Brown said bringing all medical equipment production to the U.S. isn't the solution, as the spreading pandemic could force American factories to shut down if workers become sick. "Importing medical products from diverse sources globally has huge benefits," he wrote.

Supply chains kick into high gear in the near-term

Retailers and manufacturers fall into one of two camps. Either their products are in extremely high demand, creating a bullwhip effect on the supply chain and pressuring suppliers to keep production lines flowing. Or demand is taking a hit as physical distancing and fears that an economic downturn lies on the horizon slow consumer buying.

Apparel faces the latter situation, and the first step is reducing planned incoming inventory through conversations with vendors. The industry will have to plan for inventory already in transit and how to store or repurpose excess material.

Most U.S. and European manufacturers facing high demand had enough inventory to meet customer needs in Q1, Bowen said. "The second quarter is when they're going to feel the pinch," he said.

Automotive and retail supply chains could see stock-outs as soon as May, a McKinsey analysis found.

Glideaway, a manufacturer of adjustable base beds, keeps four to five weeks of inventory on hand, said Wendy Topp, transportation manager at the company. "In two to three weeks, we're going to be scrambling," she told attendees at Modex in Atlanta on March 9.

Nearshoring is one option, although coronavirus cases in the U.S. have surpassed those in China. Ofiara described a client that produces wire cables and requires raw materials such as copper and aluminum. "They no longer are able to source in China. They had to bring that to the US," he said.

Future: Beyond trade wars and pandemics

A strategy built around risk

No one can say for certain when the COVID-19 pandemic or the trade war between the U.S. and China will end. But supply chains are already beginning to plan ahead and examine ways to mitigate as much current and future disruption as possible.

Pratt said procurement managers have begun to change how they evaluate sources and added risk as a factor in supplier scorecarding.

The trade war led buyers to qualify more suppliers to keep their options open, in addition to thinking about cost structure and long-range manufacturing plans, according to Bowen. "It started the conversation about our future supply chains," he said.

RF IDeas plans to continue building variation into its supply chain and sourcing, with a current focus on Mexico. "Moving forward we will be looking to diversify even more," Smith said. "It has opened our eyes to the potential in other countries — that there are other suppliers out there."