When schools and nonessential offices closed this spring, the need for cleaning supplies (and toilet paper) shifted from the institution to the home. Consumers snapped up cleaning products seconds after they arrived on store shelves, if they arrived at all.

Cleaning and disinfectant product manufacturers, and their retail customers, are continually out of stock and unable to keep up with the demand, said Howard Bochnek, VP of technology and scientific affairs at American Infection Control, a company developing and licensing disinfectants.

Clorox, Lysol and other manufacturers went into overdrive, ramping up supply and simplifying product lines to make manufacturing more efficient. Like many industries, the cleaning product supply chain relies on a just-in-time approach, making it difficult to radically move the output meter in a short timeframe, according to Bochnek.

Now, months after the initial rush on disinfectants, some schools and businesses are reopening, with revised cleaning procedures and increased needs for chemical disinfection.

Manufacturers navigate EPA regs, growing demand

Commercial demand is lower with partial openings than if schools and businesses had fully reopened. "It’s not as if everyone is coming back at full volume. That demand is being managed a little,” said Sridhar Tayur, an operations management professor at Carnegie Mellon University's Tepper School of Business.

But the schools and offices that are opening need increased cleaning supplies, and many are building up inventory in anticipation of a full opening later this year or next year. If one-third of pre-K to 12th grade students go to a physical classroom with the remaining two-thirds in virtual learning, the Consumer Brands Association estimates "a significant need of 9.3 million wipes or 31,000 spray bottles to clean one desk per student."

"We’ve never seen the magnitude of orders and demand placed on cleaning product companies."

Patrick Penfield

Professor of Supply Chain Practice at Syracuse University

The Environmental Protection Agency relaxed its regulatory requirements to make it easier for manufacturers to get products out quickly. Companies can temporarily skip EPA approval to switch supplies for some inert and active ingredients and do not need EPA approval for manufacturing facility and formulation changes.

Still, if companies turn to new suppliers to procure needed ingredients, they have to ensure they’re not getting counterfeit or unsafe products. That was an issue with methanol-based hand sanitizers coming from Mexico.

To date, the EPA has certified 478 products on List N as meeting the criteria for disinfecting against the SARS-CoV-2 virus, though the list doesn’t name private label products using these official registration products. The disinfectants on the list are not specifically tested against the SARS-CoV-2 virus, but demonstrated effectiveness against other hard-to-kill viruses or a similar human coronavirus.

In spite of this regulation relaxation, "the EPA process has been more complicated than originally announced, mostly because they are overwhelmed and don’t have the systems to process high volume emergency requests," said Bochnek. Part of the reason is EPA staff members are not in their offices. "They don’t have access to hard copy files ... it means it takes a little longer," Bochnek said.

Products and packaging in short supply

Disinfection can be done with an acidic, low pH compound, such as hydrogen peroxide, or an alkaline high pH compound, such as bleach, said Bochnek. Both tend to harm surfaces they disinfect.

Alternately, a more neutral pH chemistry does less harm to surfaces while disinfecting. The most successful types combine quaternary ammonium compounds (quats) with ethyl alcohol, Bochnek said. The combination makes a significant portion of disinfectants used in healthcare and other industries.

High demand products for combating COVID-19

| Chemical product | Application |

|---|---|

| Chloramine-T | Disinfectants |

| Cocamide diethanolamine | Soap |

| Dodecylbenzylsulfonic acid | Soap |

| Ethanol | Hand sanitizer |

| Isopropyl alcohol 99.8% | Hand sanitizer |

| Ortho-benzyl-para-chlorophenol | Disinfectants |

| Ortho-phenylphenol | Disinfectants |

| Sodium dichloroisocyanurate | Disinfectants |

Source: Society of Chemical Manufacturers & Affiliates

Quaternary ammonium compounds (quats)

"The most effective are in short supply and are being allocated by chemical manufacturers, as they cannot keep up with demand," said Bochnek.

Three large domestic manufacturers produce almost all the quat compounds needed in the country, he said, but they’re having a hard time keeping up with demand.

Ethyl alcohol

Ethyl alcohol, used in disinfecting solutions and hand sanitizers, are in short supply and under allocation. "The prices of a pound of alcohol has jumped up to six to eight times from pre-COVID pricing," Bochnek said. Manufacturers in the U.S. and abroad make ethyl alcohol from grain and corn, used mostly as a fuel additive.

Wipes

Domestic U.S. suppliers are not keeping up with demand for wipes, and overseas vendors are reserving much of their production for their own use, Bochnek said.

"The ideal disinfectant wipes material for most disinfectant products is also the same material that is used to make medical face masks," he said, which often leaves wipes manufacturers without sufficient sources of polyester spunlace.

Clorox brought on 10 new suppliers to help expand capacity, raw material access and production. "We're not satisfied with our service levels right now, and we have the absolute highest urgency to improve," incoming Clorox CEO Linda Rendle said on an earnings call.

Plastic containers

In addition to getting ingredients, getting containers is a problem, said Patrick Penfield, professor of supply chain practice at Syracuse University. "The plastic container manufacturers can’t supply that off the bat," he said. They need plastic storage molds, pumps and lids.

Lead times triple for ingredients

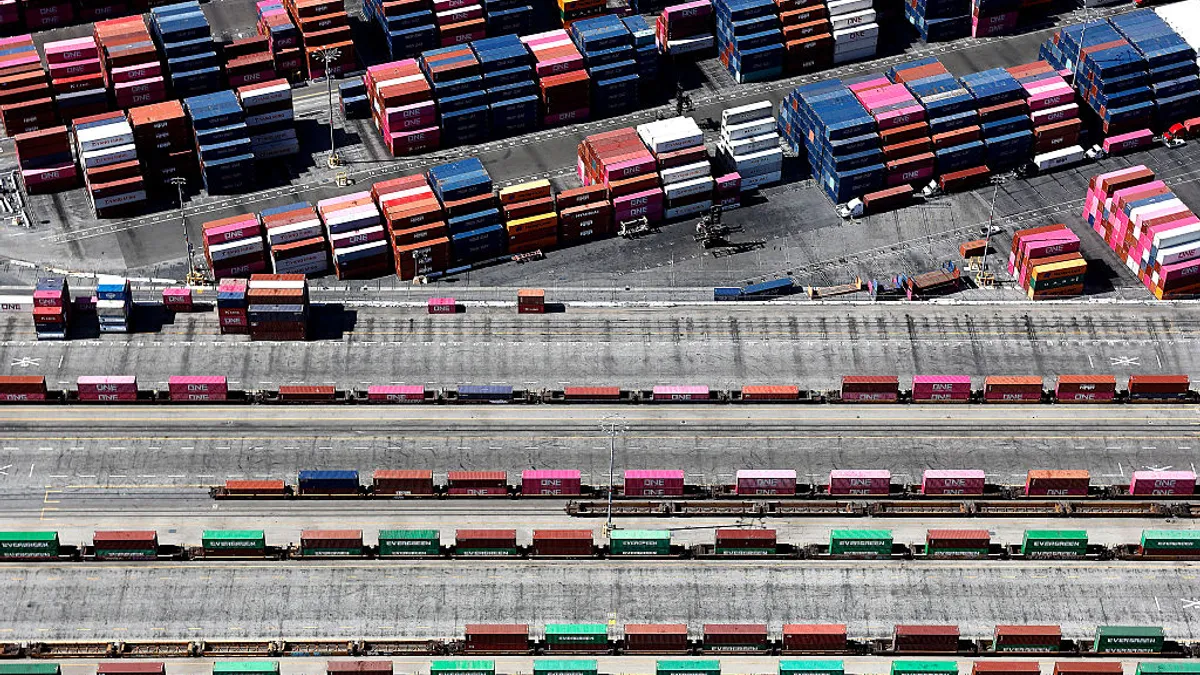

Disinfectants typically arrive by ship and must be cleared by the EPA and U.S. Customs, said Bochnek.

"Any time you put something on the water, you’re talking four to five weeks at least," Penfield said.

Then after arrival, some ships anchor offshore waiting to unload and may need another week for overland transport to the Midwest, Bochnek said.

With supply chain constraints from raw materials to transport capacity, the lead time for disinfectant ingredients doubled or tripled, even for those sourced and produced in the U.S., Penfield said. Prices will rise as a result of the demand and difficulty sourcing.

Scaling up capacity: New equipment, new skills

The demand for cleaning products is unprecedented, Penfield said. "We’ve never seen the magnitude of orders and demand placed on cleaning product companies." Usually companies look at past history for anticipated demand, but the pandemic made it hard to determine need and react. Cleaning product manufacturers also don’t carry excess inventory, he said.

Bochnek said his company is not taking on new customers and can’t keep up with current customer orders. "People place an order and say, 'I want this in six to eight weeks.' Instead, we have to tell them they’re lucky if they get it in six to eight months," Bochnek said. Contract manufacturers producing the finished product say they’re looking 12 to 18 months out, as they’re getting large orders from multiple customers.

"We have to tell them they’re lucky if they get it in six to eight months."

Howard Bochnek

VP of Technology and Scientific Affairs at American Infection Control

Most manufacturing plants for cleaning products are automated, said Penfield. To increase capacity, they have to buy specialized equipment. Equipment orders take six to 12 months to bring online.

Once the virus is under control, manufacturers could end up stuck with equipment they don’t need. "That’s the issue they’re struggling with. They want to make an investment to be heavily automated, but you have to think three to four years down the road," Penfield said.

In the meantime, some manufacturers increase capacity by adding night and weekend shifts, running continuously. But that still only addresses a portion of the demand.

The inability to increase capacity fast enough is hurting the overall cleaning product supply chain, Penfield said. "It’s like a giant dam, and they’re trying to plug holes."

"They want to make an investment to be heavily automated, but you have to think three to four years down the road."

Patrick Penfield

Professor of Supply Chain Practice at Syracuse University

Some companies outsourced manufacturing or converted previously closed factories to produce different products, like hand sanitizer. Tayur said Estee Lauder opened a previously closed factory on Long Island. "Clorox and Lysol are working as fast as they can. But others in neighboring industries who have core competencies elsewhere are using their skills to do some of these productions," he said.

Outsourcing manufacturing to third-party companies can lead to potential problems. "Whenever you’re outsourcing, you have to make sure it’s a good quality product," Penfield said. Companies also risk creating competitors. "They see demand, so if you’re training them and teaching them how to create your product, that could hurt you later on," he said.

Making wipes in cannisters, even if the material is available, is a different skill set for most manufacturers and requires different machinery. It’s easier to find contract manufacturers to blend ingredients into a bottle for spray use, said Bochnek.

Yet wipes are the most used disinfecting supplies in healthcare, for hospitals, doctors’ offices, fire departments and emergency responders, Bochnek said. He estimated that 80% to 90% of healthcare cleaning is done with disinfecting wipes. Customers are reluctantly switching to spray and paper towels, according to Bochnek. "When they ask 10 times for wipes, and we say we only have spray, they finally say, 'OK, I’ll take the spray,'" he said. "We’re dragging them kicking and screaming."

Outside of healthcare, janitorial sanitation companies use wipes, though in a lower proportion. But it’s even hard to keep them supplied with the sprays they use, Bochnek said.

While companies may simplify their product offerings, changing the formulation is another option, but it can impact effectiveness. Alcohol usually constitutes about 20% to 70% of a disinfecting solution, Bochnek said, depending on the recipe.

"There are disinfecting products made up of only quats, but they don’t kill all the germs and don’t kill so fast. That’s why we’ve developed formulas with combinations of quats and alcohol for faster and more effective kills," he said.

This story was first published in our weekly newsletter, Supply Chain Dive: Procurement. Sign up here.