Suddenly every consumer wants copious amounts of toilet paper, hand sanitizer and shelf-stable food. At the same time, the healthcare system needs ventilators and masks.

The spike in demand is evident in empty grocery store shelves and state politicians' pleas for medical supplies.

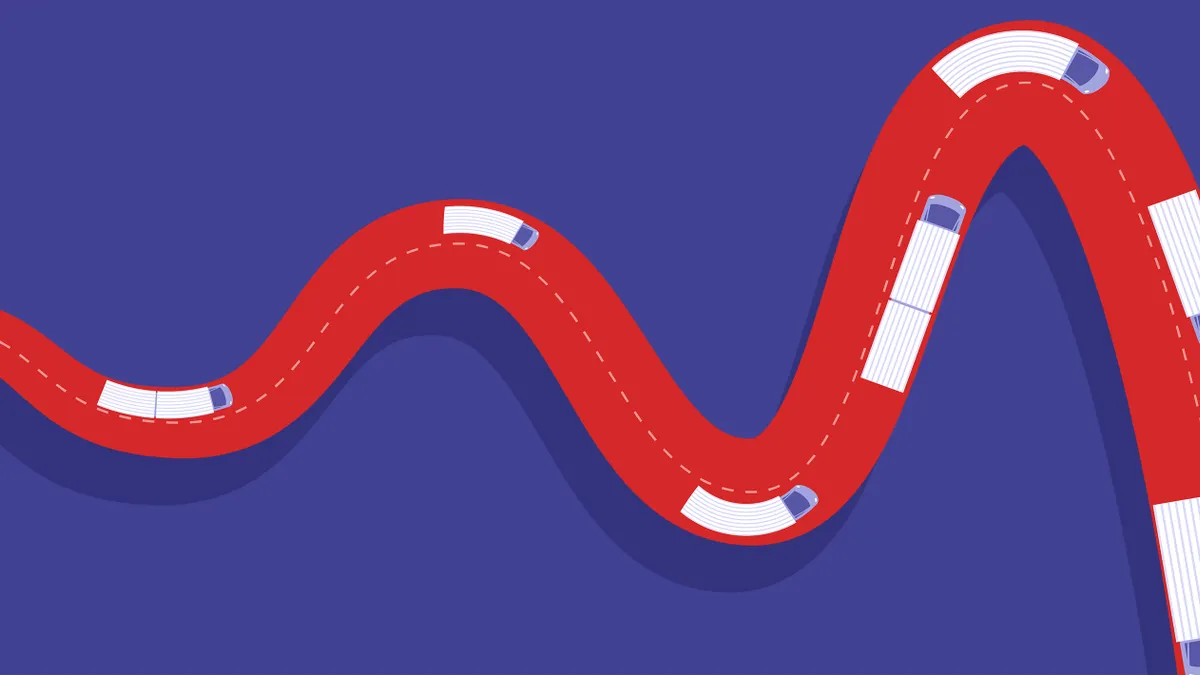

When the retail or end-user node of the supply chain sees even a slight variation in demand, it quickly ripples and grows larger as it reaches suppliers and manufacturers. In the world of supply chain, this is known as the bullwhip effect — and we're seeing it play out in real-time a the coronavirus leads consumers to panic buying and forces hospitals to scramble for supplies.

"Now what we have is probably the bullwhip on crack," Sarah Rathke, a partner with Squire Patton Bogg, told Supply Chain Dive in an interview.

As retailers' shelves empty, suppliers rush to figure out how to keep up.

"Producers are definitely ramping up to help retailers restock their shelves and make sure there aren't any outages of whatever it is there has been a run on," Pete Guarraia, the global head of supply chain for Bain and Company, told Supply Chain Dive in an interview.

There are four main causes of a bullwhip in the supply chain, according to Seungjin Whang, a professor of operations, information and technology at Stanford University who has studied the effect for more than two decades.

- Demand signal processing: An uptick in demand results in modeling techniques forecasting higher levels of demand going forward. Double or triple forecasting leads to double or triple amplifications.

- Rationing game: When demand outpaces supply, the manufacturer will implement rationing to fill orders. Under this scenario, retailers increase their order numbers beyond what they would when supply is unlimited in an attempt to get more of the item that is in limited supply. One example is a bank run.

- Order batching: When demand does not change, but multiple retailers place new orders on different days then it can appear as a change in demand that can be hard for manufacturers to interpret. It adds additional variabilities to the vendors.

- Price variation: If a manufacturer lowers its price then a retailer might increase its order size (thereby decreasing orders later on), or decrease its order size as prices go up.

Of the four, the main cause of the bullwhip in the current environment is the rationing game, according to Robert Bray, an associate professor of operation at Northwestern University who published research on the effect last year.

"Customers are getting really apprehensive about the supply being secure," Bray told Supply Chain Dive in an interview. "So they're all kind of trying to cash out the inventory that they're going to need in the next couple months in anticipation of this store sort of running out of stock, and it's kind of like a self-fulfilling prophecy."

"Now what we have is probably the bullwhip on crack."

Sarah Rathke

Partner with Squire Patton Bogg

The real-demand for consumers (i.e. how much toilet paper they're using or food they're eating) likely hasn't changed much, but their buying behaviors are imposing a dramatic change in demand upstream, he said.

Toilet paper and surgical masks diverge here, Whang said. The actual demand for medical supplies has soared, but that's not the case for Charmin Ultra Soft.

Proper procurement to manage inventory

One change in the grocery industry that has made the surge in demand harder to deal with is the implementation of just-in-time purchasing and the reduction of backroom stock, Guarraia said.

As a result, "distribution centers that back up the Costcos or the supermarkets don't have any inventories to restock the shelves," he said. This can lead to bare shelves, which then encourages more panic buying by consumers who read the signal of an empty shelf and think "shortage" even if the supply chain for that product continues to run smoothly, he said.

"I think forecasts based on the last three to six weeks of demand patterns are probably worthless."

Pete Guarraia

Bain and Company

Retail procurement managers need to put buffer capacity into their distribution centers, he said.

"The challenge is if you're doing that you're going to create a bullwhip with the key items that have been drawn down whether it's water or toilet paper or paper towels," Guarraia said.

Once retailers place orders with suppliers, the manufacturers then have to figure out how to manage the increased demand. One method is to cut down on the number of SKUs and focus on producing one as quickly and efficiently as possible, Guarraia suggested. The government might also need to step in — especially in the case of medical supplies — to help create more manufacturing capacity and build up stockpiles in the future, Whang said.

Both ends of the supply chain will need to make responsible decisions. Retailers will need to build up buffer capacity, but once that's done they'll need to return to order levels associated with normal demand patterns. Manufacturers, meanwhile, will need to figure out how to meet customer needs while not sending too much inventory into the supply chain when it's not clear whether storage and transportation will be available for the increased orders, Guarraia said.

Neither end of the supply chain has a clear understanding of real demand right now. Retailers need to effectively communicate what in their order is "real" demand — inventory to cover expected purchases — and what is meant for restocking, Guarraia suggested. This allows the supplier to know that the restocking part of the order might not be included in future orders.

Forecasting in this environment is tricky. (See the first cause of the bullwhip.) Forecasts make their predictions based on historical data and an unprecedented event like what is unfolding is hard to account for in that math.

"I think forecasts based on the last three to six weeks of demand patterns are probably worthless," Guarraia said.

But is your supplier open?

A central part of the bullwhip theory relies on the expectation that there is a next step in the supply chain — another company to interpret the demand signal. But as the coronavirus spreads, the next link could be missing. (Don't worry, the toilet paper supply chain is not in danger.)

To help fight the spread of the coronavirus, state and local governments are issuing stay-in-place orders and telling people not to leave home unless their job is deemed essential.

"What I've been spending all morning doing," Rathke said earlier this week, "is assessing to what extent our clients constitute essential businesses, to what extent their suppliers also constitute essential businesses, and their customers constitute essential businesses, and making sure everybody along the supply chain of an essential business will operate to the extent necessary to service the essential business."

Figuring out if a direct supplier is an essential business might be as easy as a single phone call. Ensuring the entire supply chain is operational? That's a little more complicated. "There's no centralized way to do it," she said. "And I don't anticipate that there will be — people are gonna have to start picking up the phone."

When does it end?

"The problem with these runs is they start and stop very abruptly," Bray said. "The only reason there's demand for toilet paper is because everyone else thinks there's this huge demand for toilet paper. It's like this nasty equilibrium. As soon as I think other people don't want toilet paper, I also don't want toilet paper."

Then demand will collapse, he said.

"What you've got to do to get things back to normal is instill confidence in the market," he said, referring to retailers. "As soon as you can kind of keep up with demand this will end because people will say, 'Oh, yeah, they're keeping up the demand.'"

Whether a procurement manager is trying to figure out the best way to buy surgical masks or toilet paper, one thing is for sure: it is a challenging environment for supply chain professionals to operate in.

"The most important time of these supply chain people's lives," Bray said.

This story was first published in our weekly newsletter, Supply Chain Dive: Procurement. Sign up here.