Nearly 3 million people in the U.S. were vaccinated on March 6 with one of the three coronavirus shots now authorized by the Food and Drug Administration — a record at that time. At the current rate of daily doses, President Joe Biden could meet his goal of 100 million shots in the first 100 days of his administration well ahead of schedule.

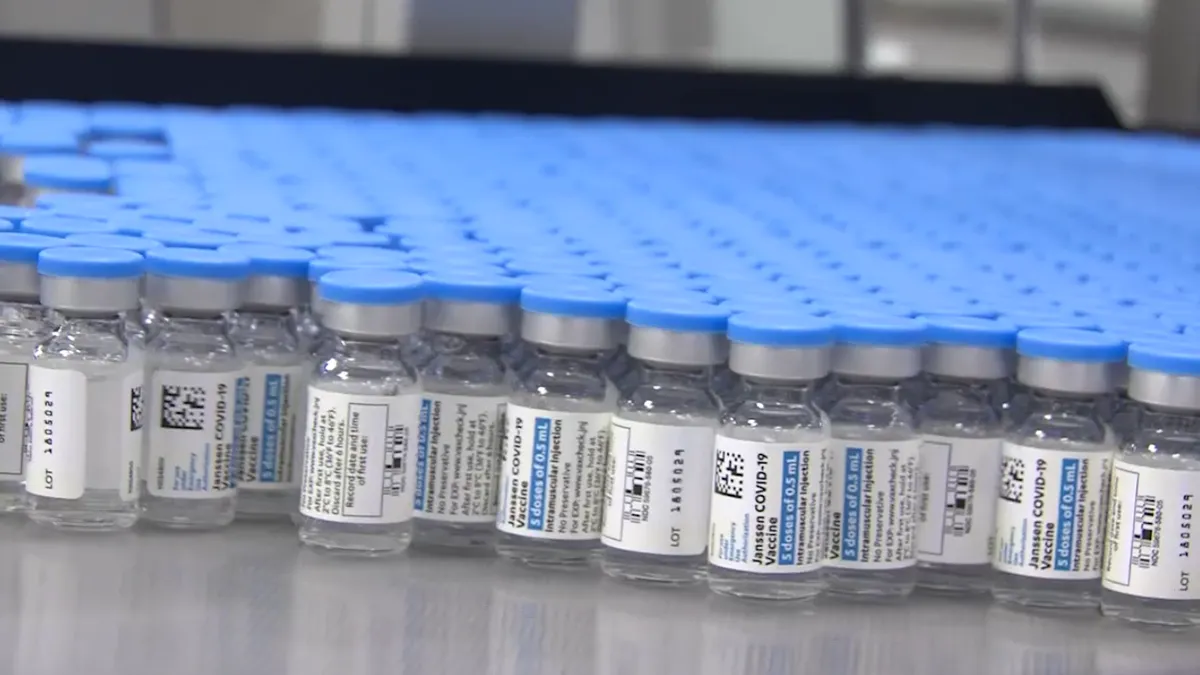

But while the Biden White House took steps to improve distribution and administration, a good deal of the sped-up pace of vaccinations is due to millions more vials rolling off manufacturing lines at Pfizer, Moderna and, most recently, Johnson & Johnson factories.

This month appears to be an inflection point in production, constraints on which have hampered vaccine rollout since December and limited availability to prioritized groups, such as healthcare workers and older adults.

Pfizer is now churning out more than 13 million doses of its shot per week in the U.S., double its rate a month ago. Moderna, which works with the Swiss contract drugmaker Lonza, also expects its U.S. production to double to more than 40 million doses per month by April.

J&J is further behind, having won FDA authorization for its one-shot vaccine late last month. But it has said it will ship 20 million doses by the end of March.

"The result is that we're now on track to have enough vaccine supply for every American adult by the end of May," said Biden at a Wednesday event highlighting a manufacturing collaboration between J&J and Merck & Co. The president had previously promised enough supply by the end of July.

Streamlining production

The current scale-up is the result of many things, including substantial federal funding and government intervention to ensure vaccine makers get needed manufacturing supplies. FDA permission to extract more doses from each vial of Pfizer's and Moderna's vaccines has also helped.

One especially significant factor, however, is the growing familiarity companies have with producing the shots, allowing their factories to work out production kinks and boost yields.

"The biggest gain we've seen — as we've now moved to 9, 10 million doses a week — has been really the incredible advances of the highly skilled personnel who are operating each step of the process," Moderna President Stephen Hoge told lawmakers on the House Energy and Commerce committee at a Feb. 23 hearing.

Pfizer's and Moderna's vaccines rely on messenger RNA to prime the body's defenses against coronavirus infection. The technology is newer and, until last year, had never been scaled up to support commercial manufacturing.

In Pfizer's case, production principally takes place at factories in St. Louis; Andover, Massachusetts; and Kalamazoo, Michigan. Initially, making one batch took roughly 110 days, a timeline the company has now worked down to an average of 60 days.

About 12 of those days are spent at the Kalamazoo plant, where Pfizer wraps the messenger RNA vaccine product into a protective bubble known as a lipid nanoparticle as well as fills and finishes vials.

About 800 staff at Kalamazoo are working on making Pfizer's vaccine, said Chaz Calitri, a company executive who manages operations at the plant. They've had success streamlining their processes, such as reducing the rejection rate on the vial inspection line from about 5% initially to between 1% and 2%.

The factory also developed a way to reuse special filters that it had trouble procuring and has begun making its own dry ice for storage on site. (The U.S. has also helped to secure supplies through the Defense Production Act.)

"We keep looking at output capacities, at the next bottleneck and what we need to overcome that," Calitri said. "Even as we add more formulation and filling capabilities, that has requirements downstream like [needing more] freezers."

For example, Pfizer has started producing its own lipids, setting one of its sites in Connecticut to the task, and will use a facility in Kansas to help out Kalamazoo with filling and finishing vials.

Making up ground

The progress on manufacturing contrasts with early struggles that led Pfizer to cut production forecasts ahead of its shot's U.S. authorization and slowed production by J&J.

Over the course of last summer, Pfizer promised 100 million doses would be ready by the end of 2020, a target it had reduced by half by the time study results showed the shot to be highly protective against COVID-19.

J&J's original supply contract with the U.S. government, meanwhile, had committed the drugmaker to delivery of 12 million doses by the end of February. But when its vaccine was authorized Feb. 27, J&J only had 3.9 million shots ready to go.

The pharma company hasn't specified what was behind the delays. A recent report by the Financial Times indicated slower-than-expected technology transfer between facilities and problems at a contract suppliers played a role.

In a recent deal brokered by the White House, Merck agreed to help J&J produce and fill vials of its vaccine, although it will need several months to ready its factories. At Wednesday's event, Biden announced the U.S. would order another 100 million doses of J&J's vaccine for delivery later this year.

"I'm doing this because, in this wartime effort, we need maximum flexibility," Biden said. "There is always a chance that we'll encounter unexpected challenges."

All told, the U.S. has pre-ordered 800 million doses from Pfizer, Moderna and J&J this year, enough for 500 million Americans. Deals with other manufacturers like AstraZeneca and Novavax could add another half a billion more.

The extensive pre-ordering by the U.S. has also drawn criticism, as much of the world still doesn't have access to the handful of vaccines that have been proven safe and effective.

Even in Europe, which has also made many high-dollar orders, production delays have slowed the rollout of vaccines and ignited political controversy. Italy, with the support of the European Union, recently blocked the export of several hundred thousand doses of AstraZeneca's shot.

On Wednesday, Biden suggested the U.S. would help with world supply, but only after completing vaccinations domestically.

"If we have a surplus, we're going to share it with the rest of the world," he said.