The global semiconductor industry is in a period of rapid change.

The U.S. is pouring billions of dollars in federal funding and incentives into building its domestic chip manufacturing industry with the help of laws like the CHIPS and Science Act.

As part of the law, the country is funding the development of its semiconductor packaging manufacturing sector and for small business chip supply chains, all in an effort to lessen its dependence on foreign imports of the critical technology.

At the same time, the U.S. has been pushing to limit China's access to advanced chips. In October, the Biden administration announced new restrictions of U.S. sales of artificial intelligence semiconductors to China. It also unveiled additional licensing requirements for shipping chips to more than 20 other countries under U.S. arms embargoes in an effort to stop advanced chips reaching China through a third country.

The U.S. push to hinder China's semiconductor industry growth underscores the ever rising importance of chips to fuel a country's economy and military. The technology underpins everything from cell phones to advanced weaponry, making a country's access to chips a matter of national and global security.

The Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals took stock of the changes and escalations in the industry this year and their impact on the global chip supply chain in a new report earlier this fall. The report takes a stark look at how the vastly complex technology products require the alignment of dozens of companies and countries across the globe, without which, the system is vulnerable to shocks and snarls.

Read on for five takeaways from the report.

1. The semiconductor manufacturing sector is highly concentrated

Chip production is concentrated in two integrated design and manufacturing corporations, Intel and Samsung, that design and make their own semiconductors. There are then three foundries, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., GlobalFoundries and Samsung, that manufacture semiconductors designed by their companies.

Advanced semiconductor memory, meanwhile, is manufactured by three companies around the globe – Samsung and SK Hynix in South Korea and Micron Technology in the U.S.

Geographically, the chip industry is predicated on stability in Taiwan, as the home of TSMC and nearly all complex logic semiconductors. The country produces 90% of the world's most powerful processing chips, and generates more than a third of the additional computing power added to the world each year, according to the report.

Such dependence on only a few companies and one country puts the industry at risk of supply shocks should any one of these players face disruption.

2. Chips rely on a highly complex global supply chain

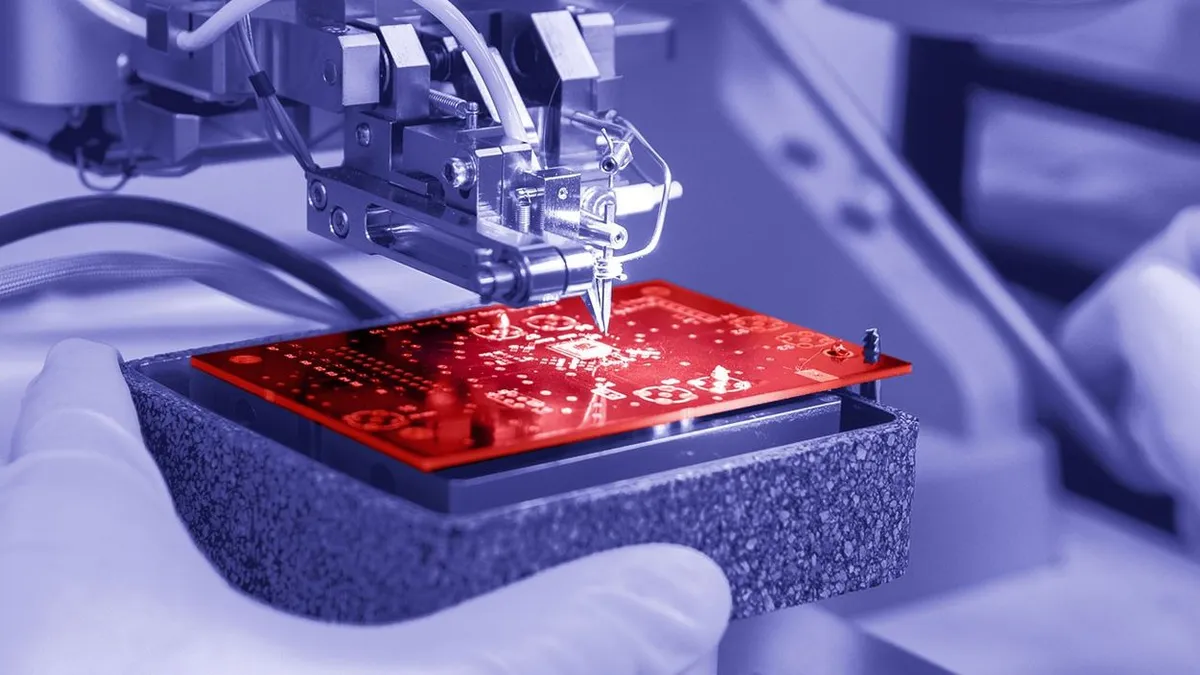

While the manufacturing of chips themselves might be dominated by a select group of players, it takes thousands of companies around the world to contribute the many raw materials and components needed to produce a semiconductor.

Chips cross international borders more than 70 times before reaching consumers, traveling roughly 25,000 miles through various stages of production. This global crisscross of a supply chain includes every stage from design to raw material procurement, component production, chip assembly, and distribution.

"The semiconductor sector is an example of how a set of complex international supply chains has facilitated a precision manufacturing process, involving the most complex machines, the purest materials, and the most expensive and specialized manufacturing techniques that humans have ever undertaken," according to the report.

Due to this complex supply chain, many people are unaware of where vulnerabilities lie and how to address them.

3. The U.S.'s hold on the global semiconductor industry has fallen

Despite its recent efforts to take a more commanding role in the industry, the U.S.'s involvement in semiconductor production has been trending down for decades, even while global revenues tick up.

Global revenues have grown a whopping 4,730% over the last 30 years, from $32 billion in 1991 to $1.6 trillion in 2022. Meanwhile, the U.S.'s share of chip production has fallen from 37% to just 12%, with 80% of chips now manufactured in Asia.

The U.S.'s trend of using more semiconductors than it produces creates a trade vulnerability that is "unlikely to change" according to the report. While the country now has greater momentum to reverse this industry decline, to do so the report states the U.S. must "invest boldly" in chip manufacturing incentives, even beyond those in the CHIPS and Science Act.

4. China actually benefited from the CHIPS and Science Act

The passage of the CHIPS and Science Act in 2022 has been a boost for semiconductor and other firms around the world, including in China.

Chinese semiconductor companies saw bumps in their stock listings on both U.S. and Chinese stock markets in the wake of the CHIPS and Science Act.

The report's authors attribute that impact to the overall increased chip demand sparked by the law, which brought business for not only U.S. firms like Intel, but for chipmakers with cheaper or differing technology options.

Other tech corporations, such as Apple and Dell, will also need not only advanced microprocessors but a variety of semiconductors that could be acquired from companies based around the world.

"If you require American semiconductors, you will almost certainly require semiconductors from other countries," the report states.

5. The CHIPS and Science Act is just a start of what the U.S. needs

The CHIPS and Science Act includes a total of $52.7 billion for semiconductor research, development, manufacturing, and workforce development.

That money, however, is not nearly enough to fortify the U.S.'s semiconductor supply chain, according to the report. It fails to prioritize the network of associated supply chains, including raw materials and reliable power and clean water, needed to produce semiconductors.

And as China takes its own steps to limit U.S. access to necessary raw materials, the U.S. needs to take further steps to ensure it has end-to-end access to the semiconductor supply chain.

The report stresses the need for public-private partnerships to support chip supply chains, as "it is not possible for a government nor the semiconductor industry to do this alone."

Trade relationships that have served the U.S. for decades may need to shift as the country considers how to strengthen its design, manufacturing, assembly and packaging capacity, while keeping costs stable.

Above all, more change is likely to be on the way.

“At CSCMP,” the report said, “we believe that we are in for an extended period of perhaps a decade or more of change in how these critically important supply chains are designed and executed.”