It is likely not a surprise the Panama Canal needs water to operate. It might be more surprising though that the canal, which connects the Pacific Ocean to the Caribbean Sea, is thirsty.

The Panama Canal, and Central America more broadly, is experiencing one of the worst droughts in its recorded history. With less water, the canal is forced to place restrictions on the amount of cargo ships can carry, meaning carriers have to limit the shippers they can serve on routes that rely on this waterway.

Carlos Vargas, the Panama Canal Authority's vice president of water and environment, said earlier this year January was the driest month the country experienced in the last 106 years. Precipitation in the Panama Canal watershed was about 90% below the historical average this year, a spokesperson for the Panama Canal Authority told Supply Chain Dive.

Water + locks = canal

Rainfall during the rainy season fills up two lakes, Gatun and Madden, which the canal relies on for moving ships through locks.

The levels in these lakes always reach their lowest points between April and July as a result of the country's dry season. But this year, Gatun and Madden have been at much lower levels than in past years — about seven feet or more below normal levels in 2019.

"Which is pretty crazy," Fred Ogden, a principal investigator for the National Science Foundation who has worked on water issues in Panama, told Supply Chain Dive. "I've never seen it that low, I think in 2015 I saw it six feet below normal."

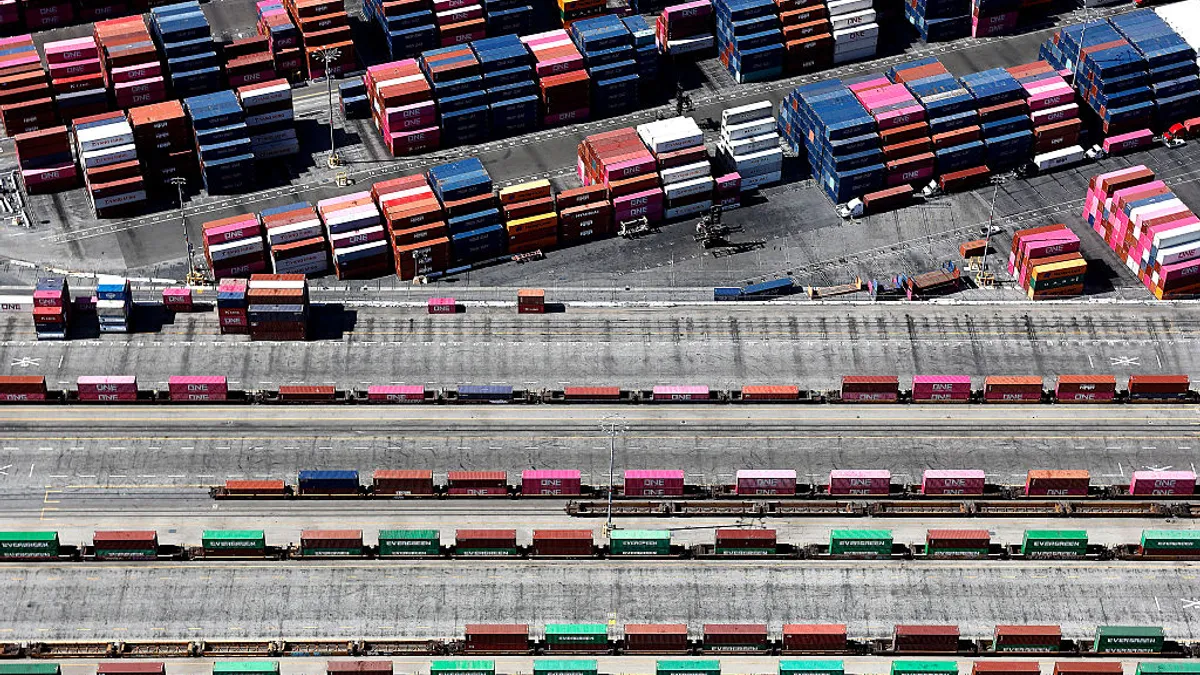

The first part of the canal to be impacted when this happens are the Neopanamax Locks. These locks were the result of the canal's expansion effort, which ended in 2016, and allowed much larger ships to navigate the waterway. This expansion has led American ports to invest in new infrastructure to support these larger ships and their increased capacity, adding space for more trade on one of the world's most important maritime routes.

But when water is in short supply, a cap has to be placed on this capacity.

When ships go through the locks, there needs to be enough water to ensure the hull doesn't run aground. The heavier the ship, the more water is needed to make sure this doesn't happen. So the canal has had to put in place draft restrictions, the "draft" referring to the part of the ship below the water line.

In May, this restriction was placed at 43 feet for the Neopanamax locks and 38.5 feet for Panamax locks. The canal has released 12 advisories on draft restrictions this year.

To meet these restrictions, ships have to carry fewer containers and for Neopanamax ships this can mean a significant reduction in cargo, according to American Global Logistics CEO Jon Slangerup.

"The new locks were designed to handle up to 14,000 containers," Slangerup said, adding that many attendees at a recent conference in Houston were talking about the issues in Panama.

"Everybody was counting on the new Panama Canal to be able to handle these big ships and, in fact, its highly constrained now because of environmental conditions due to climate change."

Jon Slangerup

American Global Logistics CEO

Carriers say they've had to limit the cargo they carry through the route as a result of the restrictions.

"Maersk vessels are restricted in their intake through the Panama Canal, which in turn makes Maersk unable to serve all the prospective end-customers, who otherwise would be utilising the canal as a route to the [U.S. East Coast] as well as Europe," Maersk told Supply Chain Dive in an email. Hapag-Lloyd told Supply Chain Dive the current restrictions were resulting in a cargo deadweight reduction of around 10%.

"Now this is a stunning development because everybody was counting on the new Panama Canal to be able to handle these big ships and, in fact, its highly constrained now because of environmental conditions due to climate change," Slangerup told Supply Chain Dive.

Less cargo, less market share

The canal has had reduced operations in the past, Slangerup said. This led to shippers looking for other routes from Asia to the U.S. East Coast, like through the Suez Canal or through West Coast ports and across rail and truck networks.

"If this constraint continues," he said, "then ... the Panama Canal will lose market share, if they haven't already. And the West Coast ports will benefit as will the Suez Canal."

So far, though, the restrictions have primarily been a concern for carriers rather than shippers, and carriers have likely made the needed adjustments to support movement through the gateway, he said.

It's hard to say just how much cargo has been held back as a result of the draft restrictions, but the projected financial losses expected by the canal begin to provide a picture. The canal charges fees based on the amount of cargo a ship has on board, so draft restrictions will also limit the fees the canal is able to collect. A Panama Canal Authority spokesperson told Supply Chain Dive it expects to lose $15 million, which is about .5% of the canal's total annual revenue, as a result of this year's drought. The Authority also said the current restrictions affect 8% of Neopanamax transits.

The canal charges two fees for carriers to use the waterway. One fixed fee based on the maximum capacity of the vessel and another variable based on the total number of containers actually being transported. Maersk said the fixed fee has not changed with the implementation of the draft restrictions.

The silver lining, for now at least, is that while the draft restrictions are still in place, the dry season is over.

"The wet season runs May through December in Panama and seasonal rains have returned so that should provide some relief to lake and lock water levels," Maersk said.

2 countries, 1 canal

The canal keeps Panama and the U.S. tied at the hip. The largest trade route to use the Panama Canal is between Asia and the U.S. East Coast — which accounted for almost 35% of total canal traffic alone in 2018. In fact, if the top five U.S. routes through the canal are added together they account for more than 55% of the traffic heading through the waterway.

Ever since the Panama Canal finished its expansion, American ports have been pouring tens of millions of dollars into new infrastructure to accommodate the larger ships that can now navigate between Asia and the U.S. East Coast. One such investment is Neopanamax cranes, which add about 30 feet in height and almost 40 feet in outreach.

But with less water in Panama to float these ships, some are worried about being able to leverage the full capacity of these newer and bigger ships.

The country looks for solutions

Panama knows it has a problem on its hands.

When Ricaurte Vásquez was appointed earlier this year as the canal's new administrator, he directly acknowledged the drought as a matter of concern. "The insufficiency of water is not only a problem of the canal, but also of Panama," Vásquez said, according to Panama Today.

The Panama Canal Authority places the blame for the drought on the warming climate, saying in a statement its plans were an attempt to "mitigate climate change." Ogden and Jefferson Hall, a staff scientist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute who has worked in Panama, said attributing any particular event to climate change can be hard. But the last few years are beginning to show a trend toward drier conditions, with the country also experiencing heavy drought in 2016 and 2017, according to Hall.

These problems are the most prominent for its newest locks and Neopanamax ships sailing through them. The average lake level at Gatun during April, May, June and July already requires a draft restriction for Neopanamax ships, according to figures in a research paper released earlier this year.

One way the country is currently looking to mitigate its water woes is through land use studies to determine the best way to manage forested land around the canal region.

"At our research site, we've shown the forests do serve as sponges so it can absorb water in the wet season and release it slowly during the dry season," Hall told Supply Chain Dive.

Ogden said this research has extended into agricultural practices to see how variables like heavy grazing can affect water levels in rivers and reservoirs.

But these changes to land management alone will not provide the saturation these lakes and locks require. This is partially why the Panamanian government adopted the National Plan of Water Security in 2016. As part of this plan, the government calls on the Panama Canal Authority to study the development of new multipurpose reservoirs. The Authority is studying three areas for new sources of water — the Bayano, Indio and Azuero regions of Panama.

The study looking at the Bayano river will be complete later this year and the two other studies will be delivered to the government by 2020, according to the Authority. The Bayano river project would not require a reservoir, but would instead use a series of small locks to divert the water where it needs to go. The other projects involve creating new reservoirs that would give the country more water to release during the dry season.

But there are some who question the sustainability of this kind of solution. The Panamanian constitution requires the canal to be operated in a sustainable manner and some question if this would fall in line with that guidance. Some argue, Ogden said, that new reservoirs can pass more sediment into lake Gatun.

"But it's a really big lake," he said of Gatun. "So I have a hard time imagining that the rate at which it's going to fill with sediment would be changed that much and ultimately they always have to dredge anyway."

The Panamanian government will make a final decision on how to move forward after the studies are complete next year, the Authority told Supply Chain Dive. Until then, the new locks will still welcome newer, larger Neopanamax ships — they just might not be full.