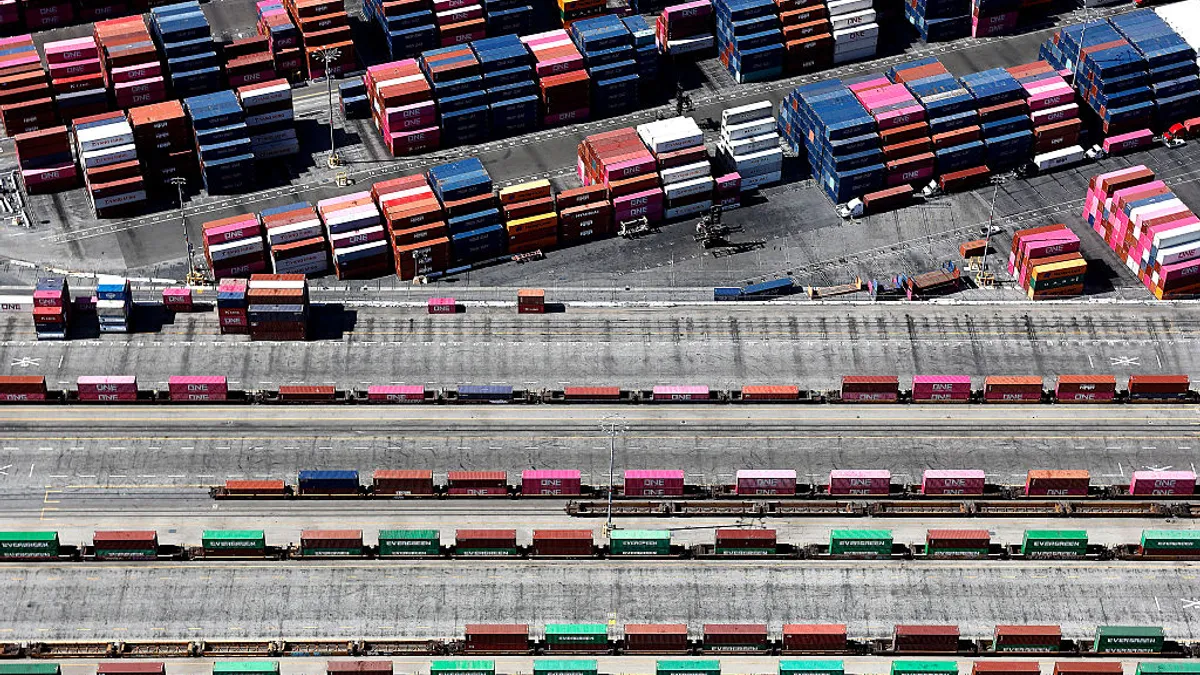

The ocean carrier comes to port and there’s no one to unload it. Or the cargo sits in port, awaiting chassis. Whose fault is this and who should pay for delays? Everyone points fingers, but the ELD mandate is now shouldering some of the blame.

As a result of the ELD mandate, “we’re seeing a significant impact on moving containers off the ship,” said Ken Kellaway, president and CEO of RoadOne IntermodaLogistics. “It’s causing bottlenecks at the terminals and at customer locations, and we’re seeing in certain key volume markets that the industry is struggling to support market demand.”

Of course, ELD is not the only culprit. U.S. port volume grew 6.47% in 2017 over the previous year, according to the National Retail Federation. There’s the truck driver shortage, winter weather causing slowdowns and Chinese New Year. But “ELD is the straw that broke the camel’s back. That’s really what’s finally put this at the forefront,” Kellaway said.

Capacity challenges vary by region

Depending on location, port container delivery challenges differ. Mark Bartmann, senior director of seafreight drayage solutions at Kuehne + Nagel, sees the challenges as short term through long term.

Short term: Areas such as Chicago are experiencing the perfect storm. First there’s cold weather, including snow and ice, which decreases road speeds and sometimes halts driving completely. Plus, “there’s unseasonably high volumes for off-peak,” Kellaway said. There aren't enough chassis available, in spite of companies bringing in extra. Bartmann anticipates the Midwest’s capacity crisis will resolve in six to eight weeks, when weather improves slightly and Chinese New Year ends.

Another issue for Chicago is a fairly long haul length, said Kellaway. “A lot of companies had to readjust their networks to be in compliance" with the ELD, leading to longer delivery times, he said. He’s using more pre-pull and relays to service the market, which consumes driver resources to accomplish the same goals.

Mid term: Regions experiencing mid-term challenges include ports in the southeastern U.S.: Savannah, Charleston and Memphis. Larger vessels are coming into Savannah and Charleston, meaning more cargo to haul. Plus, these ports are more than 200 miles from the delivery destinations, as most cargo moves to North Carolina, Georgia, Tennessee, Louisiana and Alabama. With a 14-hour work time, including 11-hour drive time, drivers can’t do that route in one shift. The average truck can cover 571 miles with no traffic, said Bartmann. A 600-800 mile round trip can’t be done in a day.

Without returning to port the same day, capacity drops. Bartmann has seen a 25% capacity crunch because of mileage issues combined with drivers doing pre-pulls. “A lot of containers are just sitting on chassis,” he said. “We just move them when we can.” That eliminates available yard space.

Long term: In the long term, Texas will have capacity challenges. While weather isn't an issue, the region is building five more resin plants, which will increase the need for transportation. Labor is an issue, as workers can make more in construction or in factories than driving trucks, and with a better lifestyle, Bartmann said.

Areas with few ELD issues: Bartmann said that the West Coast and Los Angeles area isn't experiencing port ELD issues. The longer haul distances like Reno to San Francisco are already overnight trips, so nothing drastically changes in cost or capacity. And in the Los Angeles area, many destinations are in the 100-mile range.

The Northeast is mostly not impacted either, said Bartmann. While drivers go further than in the Los Angeles area, maybe 150 miles each way, day trips are still possible, and he doesn't see a capacity or ELD challenge. Not all would agree, however. At least one trucking company in the mid-Atlantic region begs to differ.

Trucking rates go up as capacity shrinks

Bartmann said that trucking rates are rising across the country, on average 7-10%. Some lanes will be higher, due to layover costs. Motor carriers are already asking for increases. While truck driver rates are overdue for a raise, it’s still hard to pass that on to clients.

With the mandate’s implementation, Bartmann has been calling his sea freight clients in Europe, as well as educating his staff, so they can educate customers. He’s received a lot of backlash, especially from those who haven’t heard of the ELD mandate and don’t believe that it’s causing issues.

The result will be difficult discussions between beneficial cargo owners, NVOCCs and ocean carriers. “The customer can accept the additional cost. The ocean carrier can accept the loss. Someone will pay for it, and it won’t be the trucker this time,” Bartmann said.

“It can’t be one group against another. We have to make it an attractive industry to come in and work, or we’re all in trouble.”

Ken Kellaway

President and CEO, RoadOne IntermodaLogistics

When negotiating a four-year contract with a client last year, Bartmann didn't anticipate the mandate causing this much capacity crunch or increased costs, as his company plans freight in advance and pre-dispatches trucks. He didn't foresee it impacting his own business. He recently had to renegotiate that four-year contract. The customer, which ships 40,000 TEUs, accepted a rate increase because their cargo is pre-pulled because of the ELD changes. “We made a logical explanation. We apologized. But account by account, it’s a very difficult discussion,” he said.

As demand for motor carriage increases, the power is shifting toward truckers. “Ocean carriers have failed in the last few years, by seeing trucking as a commodity, not seeing motor carriers as people, just a burden,” Bartmann said. “Whoever has abused the motor carriers will get a backlash."

What has to change

As a result of the ELD mandate and capacity crunch, Kellaway says the industry needs to work together. “It can’t be one group against another. We have to make it an attractive industry to come in and work, or we’re all in trouble,” he said. That includes improving freight efficiency at the terminals. Reloading equipment should be more efficient too, to reduce the number of empty miles.

Kellaway noted a new initiative his company is part of called E*Dray, an early stage transportation company that's launching across the country right now. It’s trying to improve how intermodal companies collaboratively move containers in and out of ports.

Qualified transportation companies move other customers’ freight within certain geographic zones, using a taxi cab approach. The first qualified truck picks up the first available container, and reconciles the accounts later. “We think it will get us in and out 30-40% faster,” Kellaway said, which will help with the hours of service requirement.

“Being a truck driver isn’t favorable anymore. If you’re an American and you have your health, you’d rather go into construction or one of the factories going up ... You have your routine every day and make more money.”

Mark Bartmann

Senior Director, Seafreight Drayage Solutions at Kuehne + Nage

Another thing that needs to change, said Kellaway, is that drayage companies can’t be held liable for delays and penalties when they don’t have full control the delay. Drayage companies operate on small margins, and the one day detention penalty on a container is more than the margin on moving the container. An average drayage load is $300, he said, and a detention charge could be $150 per day. If the trucker is making a $15-20 margin on that business and misses one day, it takes 10 moves to make up the margin.

Drivers tempted by other work

Of course, another solution is to increase truck driver wages. The truck driver shortage isn't news, but Bartmann sees competition for that labor as fierce, especially in the southeast and Texas, due to competition from other industries.

With lower hourly wages and mandated rest time sometimes away from home, “Why would you do this for a lower paying job?” said Bartmann. “Being a truck driver isn't favorable anymore. If you’re an American and you have your health, you’d rather go into construction or one of the factories going up, where you work eight hours with a one hour break. You have your routine every day and make more money.”

With the move toward self-driving trucks, potential younger drivers may be less interested. “If you were an 18-year-old coming out of high school or 25 coming back from the military and need a job, why would you get a CDL and then go into a two year program before you can even drive the big rigs on the road, if you know that in a few years, there will be self-driving trucks?” Bartmann said.

Trucking companies aren't just competing with other trucking companies for drivers, but other transportation sectors as well. That means final mile drivers for e-commerce shipping, and Uber. “As an industry, we have to make it attractive for drivers,” said Kellaway.