The global appetite for electric vehicles is growing, but questions remain about the viability of the EV battery supply chain. Demand might increase so quickly in the near term that the supply chain could have difficulties keeping up.

In October 2018, J.P. Morgan forecast that by 2025, EVs and hybrid-electric vehicles will account for an estimated 30% of all vehicle sales. In comparison, that figure was just 1% in 2016.

"Electrification has accelerated in the eyes of government and the policy sectors," said James Nicholson, a partner with consulting firm EY-Parthenon. "It’s accelerated in the eyes of the consumer, in terms of their expectations around electrification, and the numbers that will actually buy or would consider buying [an EV], so there’s a natural supply and demand imbalance that’s coming."

One supply chain problem is the lag in manufacturing the cells that make up the batteries. Tesla CEO Elon Musk said in October that issue is keeping the company from ramping production of its Semi. He reiterated the issue on Tesla’s earnings call in January, that cell availability is "the fundamental limit on electric vehicles right now."

"We are scaling a supply chain that was capable of supplying the consumer electronics industry to supply the transportation industry," said Celina Mikolajczak, vice president of battery technology at Panasonic Energy of North America, one of the leading manufacturers of EV batteries.

Mikolajczak noted that a cellphone has one battery cell, and a laptop has a dozen cells. But a typical electric car requires thousands of cells.

"How do you quickly scale an industry by 100 times?" she said. "You need more raw materials, the skilled talent and machines to extract the raw materials, the factories to process the raw materials into cell components, and then the factories to turn those components into cells."

Supply chain obstacles: parts and minerals

The components necessary to produce EVs differ from what's needed to produce internal combustion engine vehicles. According to Nicholson, about 25% of the ICE vehicle supply chain doesn’t translate into the EV supply chain. EVs don’t have as many parts as ICE vehicles.

"Let’s say it’s 10,000 parts in an [ICE] car and 4,000 parts in an EV. If I make seats, that’s fine," Nicholson said. "But if I make engine valves or spark plugs, I’m isolated; I don’t really have a future."

Nicholson said to combat this problem, vehicle manufacturers have realized they need to make the batteries, too, where about 40% of the value of an EV is contained. That’s why companies such as Tesla, General Motors, Toyota and others have begun making their own.

"How do you quickly scale an industry by 100 times?"

Celina Mikolajczak

Vice president of battery technology at Panasonic Energy of North America

"You don’t want that value going elsewhere," Nicholson said. According to a 2019 McKinsey & Co. analysis, the EV battery market in 2018 was dominated by China, Japan and South Korea, with less than 3% of demand supplied by battery companies based outside those countries. Europe and the United States are playing catch-up.

"You’re seeing in the European Union and in North America ... a spectrum of encouraging and incentivizing localization" for battery production, Nicholson said.

But to make the batteries, obtaining and refining raw materials are obstacles.

The primary materials in cells are lithium, nickel, cobalt, manganese, aluminum, copper and graphite. The first three are giving possibly the most trouble to manufacturers.

"There’s plenty of lithium around in the ground. There’s not a physical shortage of it," Nicholson said. “But there’s an economic shortage of it, which is the lithium prices don’t support the mining investment that’s required to get it out of the ground profitably. You need lithium prices to lift to deploy the capital to dig the mines to get the lithium out into the supply chain."

The problem with nickel lies in its refinement, a process that is cheaper in Asia than in North America and Europe.

"There are sources of nickel in North America and Finland and Russia and in the Far East and in China, but you also have to refine the nickel, and there’s a limited number of places you can do that," said Nicholson, indicating most of that capacity is in China, making it cheaper for companies in the West to refine raw materials there.

Most of the world’s cobalt is contained in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which has been derided for its controversial mining practices. But Nicholson explained that battery manufacturers have been able to use proportionally more nickel and lithium in newer generations of batteries and less cobalt in an attempt to eliminate the inherent risk that sourcing cobalt carries.

"Panasonic has already established the technology to produce cobalt-free batteries, and it is expected to be commercialized within the next two to three years," Mikolajczak said.

Charging up a regional supply base

As vehicle manufacturers dip their toes into making batteries, they're also partnering with and investing in battery companies. "That’s helping them secure supply by being strategic investors and helping the capital to flow," Nicholson said.

Volkswagen and BMW have invested in battery manufacturer Northvolt. GM is building its Ultium Cells plant with LG Chem in Lordstown, Ohio, where GM in 2019 closed an ICE vehicle plant. And Tesla is entering long-term agreements with its preferred suppliers to secure capacity and favorable pricing.

Companies realized during the COVID-19 pandemic that it is important to have strong relationships and numerous suppliers, so that one failure in the supply chain doesn’t halt production, Nicholson said.

"The most important thing for the automotive sector as a whole is that you have a flourishing regional battery supply chain," Nicholson said. "Not just of the cells, but with the materials, the supply chain that sits behind it. ... What they don’t want is concentration of supply outside of their regions where they make the cars. That won’t help them."

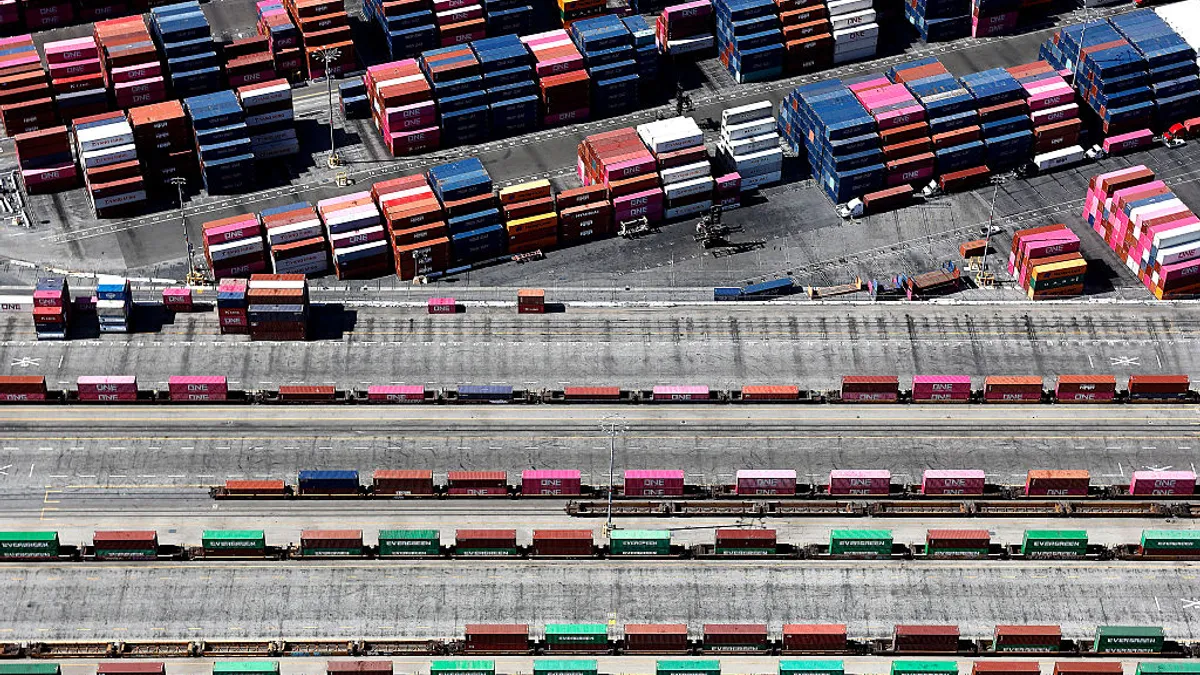

A regional supply base also cuts down on transportation emissions between nodes of the supply chain, which is particularly important for an industry such as electric vehicles that prides itself on sustainability.

One company working on sustainability is Carson City, Nevada-based Redwood Materials, which has partnered with Panasonic to recycle battery waste from the Tesla Gigafactory. Redwood also has partnered with Amazon to recycle EV and other lithium-ion batteries from parts of its businesses.

Alexis Georgeson, vice president of communications and government relations at Redwood Materials, said the company is focused on creating a circular supply chain. She noted Redwood is the largest battery recycler in North America, receiving about 2 gigawatt hours of material annually, which equates to about 30,000 cars.

"The most important thing for the automotive sector as a whole is that you have a flourishing regional battery supply chain."

James Nicholson

Partner with consulting firm EY-Parthenon

"We’re recovering about 95%-98% of the nickel, cobalt, lithium [and] copper from the batteries and focused on returning those raw materials back to battery and EV manufacturers," Georgeson said.

A self-sustaining supply chain would mean companies wouldn’t have to rely on mining as much to obtain raw materials, since they could be pulled from the waste.

The innovation shown at Redwood is an example of what can move the EV battery supply chain forward. Treating EV batteries like any other commodity is what could hold back the industry, according to Nicholson.

"We’ll fail as an industry if we focus too much on lowest-cost sourcing at any cost for the cheapest possible internationally imported battery as if it were just another commodity like a wheel nut," he said. "If we do that, we’re not going to grow a sustainable supply chain, and the long-term value will be eroded."

This story was first published in our weekly newsletter, Supply Chain Dive: Procurement. Sign up here.