This year has been an uphill battle for the electronics sector. A March McKinsey study cautioned that electronics companies could stock out by April due to coronavirus-driven factory shutdowns in China and extended lead times.

The shutdowns in China impacted "about a month to 45-day cycle," Richard Barnett, chief marketing officer at Supplyframe, told Supply Chain Dive. “And [production capacity] is coming back to maybe 5% to 10% lower than year over year, seasonally adjusted.”

The industry rapidly turned to suppliers in other Asian countries and doubled down on existing diversification strategies put in place during the U.S.-China trade war. But the moves did not eliminate or mitigate risk altogether. Fifty-three percent of respondents in a survey of 217 electronics industry leaders, released in May by Supplyframe, said new product launches have been delayed or canceled due to the pandemic, and 37% said their component costs have increased.

While supply chain teams are working to mitigate and recover from these challenges, preparing for a post-pandemic new normal, trade tensions between Beijing and Washington, D.C., never went away. The Phase One trade deal, which took effect in February, reduced some tariffs and prevented rate increases in certain lists, but the Trump Administration has since rebuffed industry calls to restore duties to their pre-trade war levels.

This leaves many industries, and the electronics sector in particular, caught between two fires: ongoing tariffs and a pandemic that is shutting down factories, slashing global economic demand and calling conventional supply chain management practices into question.

Will the electronics sector break up with China?

Shifting operations is a mammoth undertaking for the electronics industry. Many large technology companies and OEMs can’t afford to give up on China due to its specialized production capacities, co-location of key suppliers and economies of scale.

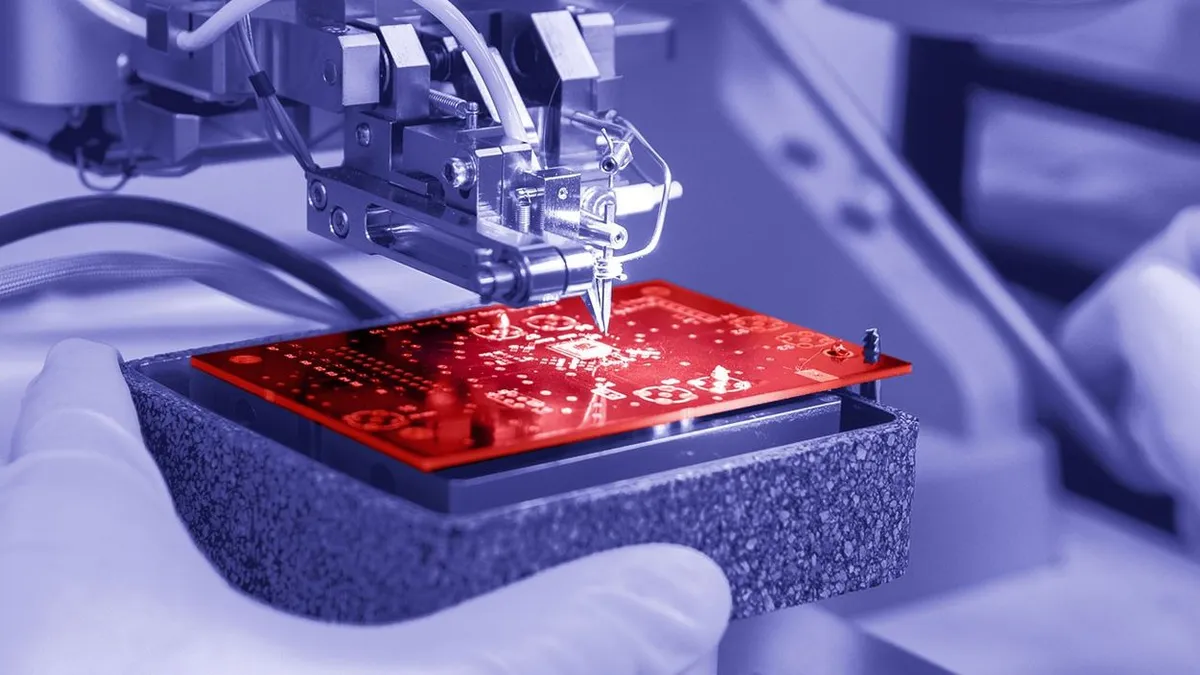

Electronics manufacturing requires an increasing level of specialization. Outside of China, the ecosystems of qualified suppliers and skilled labor are less concentrated, making it difficult to shift operations entirely from one country to another. When the coronavirus crisis hit, OEMs struggled with a lack of visibility into their contract manufacturers’ operations in China. And the pandemic’s unpredictable spread sparked lockdowns in different countries at different times, making the shift out of China even more complicated.

Before the coronavirus was on anyone’s radar, tariffs on imports from China significantly eroded margins across tech sector manufacturing companies, ramping up the pressure to seek alternatives.

Many supply chains diversified toward Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam as the coronavirus pandemic caused production slowdowns in China and choked off supply of key components, such as semiconductors or finished electronics devices, although China still dominates electronics imports to the U.S.

"Before the pandemic started, we were dealing with the tariff situation from last year," Mike Mohan, president and CEO at Best Buy, said in the company’s Q1 earnings call May 21. "And so, our teams have been working tirelessly around countries of origin and our sourcing from all of our partners."

Given China’s existing supply and production infrastructures, some companies, including Apple, have opted to stay put, as remaining in China and producing for China’s growing market holds promise.

Phillips currently produces 70% of its audio devices and 20% of its total product mix in China. "As China grows, the number of consumers more interested in brand and product quality instead of price is expected to increase," reads a company fact-sheet. "[And] as its economy continues to mature, China will contribute significantly over the next few years to Philips top-line revenue."

It’s a strategy more large multinational companies, including Apple and Nike are taking as well, Doug Barry, senior director of communications and publications at the US-China Business Council, told Supply Chain Dive in an interview. Companies are considering regionalizing the supply chain within and for the Chinese market, capitalizing on that growth over the long run, he said.

For these reasons, while HS 85 electronics imports from China declined by nearly 30,000 TEUs from Jan. 1 to July 19, according to data compiled by Descartes Datamyne, overall the country remains nearly as much of a manufacturing mainstay as it did during the height of the trade war despite financial and operational disruptions.

"If you look at [large OEMs'] supply chains across two or three tiers, they're always going to have a significant footprint in China."

Richard Barnett

Chief Marketing Officer at Supplyframe

According to a study from PwC and AmChamChina conducted in April, 84% of respondents (representing multiple industries within manufacturing) had no intentions to move operations or production out of China, and 74% said they had no plans to move sourcing.

"Increasing tariffs costs are real and they shift the relative incentives but ... if you look at [large OEMs'] supply chains across two or three tiers, they're always going to have a significant footprint in China," Barnett said.

PwC predicts firms will move toward a China +1 strategy after the pandemic subsides — relying on China as a mainstay while looking to alternative countries for sourcing opportunities on a strategic basis.

Is nearshoring an option?

Nearshoring operations to Mexico can be beneficial for U.S. companies attempting to reduce their tariff exposure, but the move is not without complications.

One of IPC's member companies, a circuit board manufacturer, has switched to producing printed circuit boards for ventilators. The boards are produced domestically, sent to China to have the required chips installed and then re-imported back to the U.S., a costly and lengthy process which John Mitchell, president of IPC, said could be done more cost-effectively in Mexico as the local electronics manufacturing industry grows.

Roughly 38% of printed circuit boards come through Mexico, he told Supply Chain Dive. "And it's growing, which is great," he said. "So having challenges to that supply chain can be devastating to production of these necessary goods," from aerospace to ventilator components.

The manufacturer is currently exploring the option to shift the manufacturing process to Mexico, Mitchell said, however broader economic and trade uncertainty caused by the coronavirus outbreak has complicated and pushed back those plans.

"Going back into Mexico does make sense," Barnett said. Advantages include lower labor costs relative to the U.S. and China, and proximity to customers, meaning faster fulfillment and distribution times.

However, the disparity between which businesses are considered essential and which workers must stay at home, and for how long, across Mexico and the U.S. are causing bottlenecks.

"Obviously we need electronics to go into ventilators," Mitchell said. "But there may also be a paper factory that needs to create the warning labels or the operations labels that might not be thought of as essential. But you need to know how to use the machine right?"

In the meantime, as lockdown measures take hold in Mexico amid increasing numbers of COVID-19 cases among factory workers, some companies are yet again caught in the middle as China gradually reopens.

The trade war and pandemic aside, electronics companies have a recession to face. In order to weather the current disruption and survive over the uncertain months to come, Barnett says now is the time to reassess the fundamentals of the supply chain and innovate.

To move past the pandemic, electronics supply chains need to upgrade

Despite the cutting-edge technologies rolling off its factory lines, the electronics supply chain industry has been "left behind," according to Barnett, due to a reluctance to move away from tried and true methodologies to more agile and resilient modes of planning.

Since the coronavirus pandemic hit, 31% of Supplyframe’s survey respondents said they are onboarding new suppliers "without going through approved vendor qualification processes," in order to speed up access to critical inventory.

In addition, the pressure to cut costs has not let up as sourcing managers scramble to secure inventory. "Most of the executives that I've been dealing with in the last few years feel like they're in a straitjacket," Barnett said. "And they've just been told by the CFO, or the commercial business unit that they're servicing, to just go get cheap parts, go hit those cost targets for this quarter and then hit repeat, with no room to rethink … [or] retool how their teams work with greater intelligence."

Ninety-one percent of respondents said sourcing issues were the key cause of product delays, and those sourcing issues often stemmed from a disconnect over the cost and availability of components between engineering and procurement teams.

Bringing in sourcing managers early on can avert miscommunication, the report finds, and it can help firms respond more strategically to crises like the trade war or COVID-19 when shifting suppliers and finding component alternatives on short notice is critical.

"Most of the executives that I've been dealing with in the last few years feel like they're in a straitjacket."

Richard Barnett

Chief Marketing Officer at Supplyframe

This process also involves building redundancies into the supplier base, Barnett said, so products that typically have only one supplier would then have an alternate. Or, he said, companies can spread their production mix more evenly across existing suppliers so that if one goes down, the majority of their inventory doesn’t go down with it.

To achieve this takes additional time and money, however, requiring electronics supply chains to shift their priorities from low-cost to high-resilience modes of operation and investing in digital transformation to make the supply chain more agile, Barnett said.

This requires moving away from long-held tools such as using Excel spreadsheets to store and analyze data, or relying on infrequent, in-person supplier visits to qualify international suppliers — especially now that the pandemic has placed potentially enduring restrictions on travel and face-to-face meetings.

However, as more supply chains explore a China +1 model and scramble to find and qualify new suppliers to avoid tariff burdens or coronavirus-related disruptions, Barnett said, streamlining internal operations can set a supply chain up for success now and going forward into an uncertain economy

This story was first published in our weekly newsletter, Supply Chain Dive: Procurement. Sign up here.