Food and agriculture businesses remain vigilant one year after JBS USA suffered a ransomware attack in late May 2021 that temporarily shut down its slaughter plants and meat processing in North America and Australia.

The U.S. subsidiary of Brazil's JBS SA, the world’s largest meat supplier, processes about 20% of America’s meat supply. The company paid $11 million in ransom to cybercriminals a week after discovering the incursion.

Potential points of entry span a sweeping supply chain, legacy equipment and systems that lack modern security tools. Threat actors are exploiting these weaknesses when companies are most vulnerable.

Multiple cyberattacks have hit the industry during the past year, and the FBI recently warned food and agriculture cooperatives could be prime targets during the critical planting and harvest seasons. The agricultural machinery producer AGCO was hit with a ransomware attack on May 5, just 16 days after the FBI warning.

Most of the security teams in food and agriculture are still cataloging assets and identifying connected systems with the greatest exposure, Gartner research VP Katell Thielemann told Cybersecurity Dive in an email.

A trend is emerging, following targeted attacks during the height of the citrus export season on JBS, agriculture and farming supply coops, machinery producers and South African ports, Thielemann said.

“Food and agriculture seems to be on a few peoples’ radars these days in a way we haven’t seen before,” Thielemann said.

The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) designates food and agriculture as one of the 16 U.S. critical infrastructure sectors, encompassing about 2.1 million farms, 935,000 restaurants and at least 200,000 production and processing facilities.

While food and agriculture businesses are aware of the threat posed by ransomware, particularly after a spate of highly publicized and damaging attacks last year, many remain unprepared to counteract the risk.

Threat actors initiated ransomware attacks against six grain cooperatives during last fall's harvest, followed by two attacks earlier this year, potentially disrupting the supply of seeds and fertilizers, according to the FBI.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine exacerbated the global food supply crunch. Food prices have soared almost 30% in the past year, according to the United Nations. Other macroeconomic factors are also testing the industry’s ability to feed people, including grain shortages, climate change, and the highest inflation rates in decades.

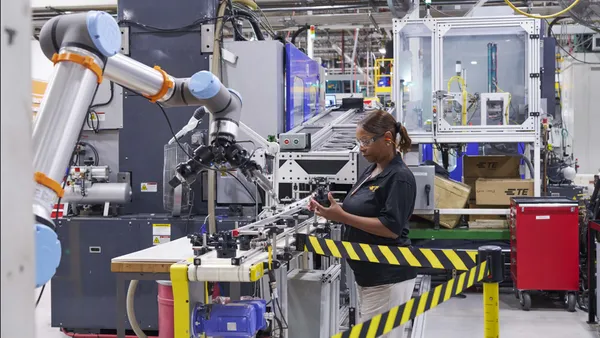

Operational technology (OT) assets, widespread in the food and agriculture sector, are partly to blame for the security risk.

“Much of their machinery runs on legacy OT that was never designed to be connected to the internet,” Grant Geyer, chief product officer at Claroty, said via email. “OT networks predate the internet, and with digital transformation leading organizations to automate parts of their production processes, OT is suddenly being exposed to a whole host of new cyberthreats lurking the web.”

Food and agriculture businesses rely on a broad ecosystem that requires extensive information sharing among farmers, transportation companies, processors and distributors. This includes a vast pool of third-party automation vendors that maintain site-to-site access into the OT environment, Geyer said.

“With so many potential OT entry points, attackers don’t even need to transit the IT/OT boundary to wreak havoc,” he said.

Security teams must consider resiliency of the entire supply chain, including multiple handoffs, while also contending with some outdated systems and equipment that can’t be patched frequently during round-the-clock operations.

Commonly exploitable vulnerabilities, such as weak or obsolete user credentials, were the culprit behind many recent attacks.

Consolidation and a concentration of companies responsible for the global food supply presents another unique point of risk, according to Thielemann. Food shortages during COVID-19 and the more recent baby formula shortage spotlight the industry’s lackluster resiliency and potentially far-reaching impacts.

“A coordinated attack on food and agriculture would lead to empty shelves nationwide in under a week,” Thielemann said. “And you don’t raise chickens or corn at will.”