Ultrafast delivery startups and established grocers each have a few things the other increasingly covets, experts say. Quick-commerce firms crave legitimacy, supply chain heft and optimally located real estate, while retailers are looking for ways to speed up service, enter valuable urban markets and extend their appeal with younger consumers.

Considering all of this, would a tie-up between the two very different sides make sense?

U.K. grocery giant Tesco answered that question in part last week when it announced a commercial partnership with Germany-based Gorillas. Under the pilot program, Tesco will co-locate Gorillas micro-warehouses at several of its stores in the London area, offering a limited assortment for delivery by Gorillas to shoppers’ in 10 minutes or less.

Also last week, Carrefour and Uber announced they would offer 15-minute delivery in Paris that relies on dark stores run by the startup Cajoo, which also counts Carrefour as an investor. And in September, leading food delivery firm Deliveroo announced it would test a 10-minute service with U.K. grocer Morrisons in southwest London.

Ultrafast startups that deliver goods from tiny warehouses to shoppers in population-dense markets in 15 minutes or less have zoomed across Europe and generated significant buzz throughout the continent. In the U.S., these firms are just starting to get acclimated, with the majority currently duking it out in New York City.

That relative newness makes it difficult to determine at this point whether an operational partnership could be beneficial, said Laura Kennedy, senior lead analyst with CB Insights. Ultrafast firms still have a lot to prove in the U.S., and will be challenged by rising real estate prices and lower population density in many markets compared to Europe. Many big-name grocers like Kroger, Walmart and Publix thrive in the suburbs and likely wouldn’t need dark stores like the ones Gorillas builds in those areas, she said, while companies like Target and The Giant Company are building dedicated urban formats.

Instant delivery firms that offer promising technology, warehouses, consumer marketing or some combination of key assets, though, could prove to be a useful partner for grocers that want to quickly expand their presence in a major metropolitan market or some other high-density area, said Jackie Tubbs, an analyst with CB Insights. She cited Walmart, which has tried to break into the New York City grocery scene a few times, most recently with the now-defunct Jet.com, as an example. Convenience-store retailers, which carry many of the same products as ultrafast startups, might also be natural bedfellows for these firms, she noted.

Jason Soar, former e-commerce lead with Sainsbury’s and now CEO of consulting company ThinkThru, sees Tesco’s partnership with Gorillas as a low-risk way of testing the waters with a new service, and said he expects other mainstream retailers in the U.K. to forge similar partnerships. Because they’re in a hurry to scale up and deliver results for investors, quick-commerce firms like Gorillas, he said, need supermarket chains more than the other way around, which can result in favorable terms for established retailers.

“My guidance to [U.S] grocery retailers would be to start to develop relationships with potential [quick commerce] operators now,” he said.

Retailers may balk at the idea of linking arms with such a young industry — many ultrafast companies were founded in the midst of the pandemic last year — but Soar believes companies need to learn what they can about an app-based, quick-fulfillment model that appeals to young consumers. “You cannot afford to be caught napping,” he said. “The consumer has more control than ever before, [and] speed and accessibility is the game we have to play today.”

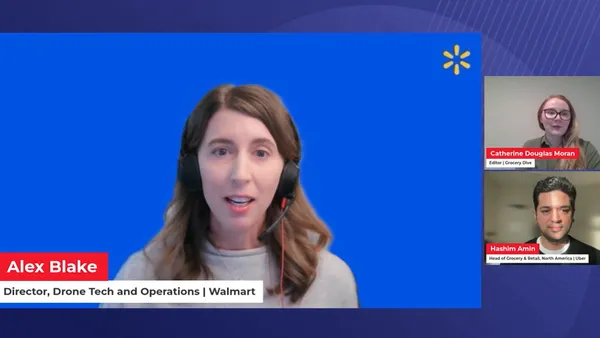

Grocers have shown a willingness to forge partnerships as they address faster delivery, namely with Instacart and its 30-minute convenience service. DoorDash is also exploring urban dark store services for grocers based off its DashMart convenience store warehouses, said Fuad Hannon, the company’s head of new verticals, while Gopuff linked with Uber earlier this year on an “everyday essentials” delivery service.

Much may depend on how ultrafast firms expand and evolve over the coming months. Matt Newberg, who founded food tech news site Hngry.tv and closely follows quick-commerce firms, said the model ultrafast firms have utilized to date, which relies on couriers ferrying goods by bike or scooter within a tight radius around dark stores in as little as 15 minutes, will likely need to evolve in the U.S. given lower overall population density and other restrictions. In Chicago, 16-store Go Grocer has held acquisition talks with multiple ultrafast startups, indicating the firms may eventually operate their own storefronts in order to boost revenue and be able to sell alcohol.

“At some point you start running out of European-like metropolitan cities that can get you essential services in 15 minutes. And then the question is, where is that other growth going to come from?” Newberg said.

Experts are in agreement that the coming years should bring significant consolidation in ultrafast delivery as firms burn through investor cash and put themselves up for sale. Stronger players will likely buy up the weaker ones, but retailers could also get in on the acquisition frenzy, said Kennedy.

“I could see a Walmart or Kroger that's inexperienced in this super fast, dark store thing — they could just buy [an ultrafast company] to just have it, and learn from it,” she said.