Driving around for hours, stopping at multiple stores, competing with retailers and private consumers for product: That has been the reality this summer for Hunter Thurston, the liquor buyer and bartender at The Crunkleton in Charlotte, North Carolina.

A once straightforward process of driving down the street to pick up a liquor order has ballooned into trekking all across Mecklenburg county to secure a piecemeal assortment of spirits — the tail end of a procurement process that is suffering from demand whiplash.

"The turnaround time used to be anywhere from 2 to 3 hours, now it's been almost 48 hours," Thurston said. "If you're a small business, big business, whatever it is … you place your liquor order, you got to hope that everything is in stock, and that the system is updated."

The issue has persisted since the end of June, with liquor shortages impacting premium, mid-shelf and lower-tier products alike, he said.

Bars and restaurants throughout the state have struggled to fill shelves with alcohol as customers ventured back out after COVID-19 mandates were lifted, just in time to start the summer season. And the heightened demand is straining supply.

The North Carolina Spirits Association and Mecklenburg County Alcoholic Beverage Control Board issued a joint statement last month addressing the product challenges. North Carolina is one of 17 states that regulate the sale of alcohol through a control system.

"Easing COVID 19 restrictions has resulted in an explosive comeback in the on premise industry," the board said in the statement. "Consumer retail sales in Mecklenburg County ABC stores continues to outpace prior year sales. The increased demand on both sides contribute to the current conditions."

But these conditions are not relegated to a single place. They are far-reaching and shaping how alcohol brands plan for the rest of the year into fiscal year 2022.

The supply chain quagmire

On its 2021 Q1 earnings call, Constellation Brands CEO William Newlands pinpointed "robust consumer demand" as a leading factor causing current inventory strain as supply can't keep up with expectations. The company includes the Casa Noble and Svedka labels.

February winter weather in Texas and Northern Mexico triggered delays that resulted in tight inventory during the summer, Newlands said. But the company is working with distributors to meet the demand, while also addressing other supply constraints.

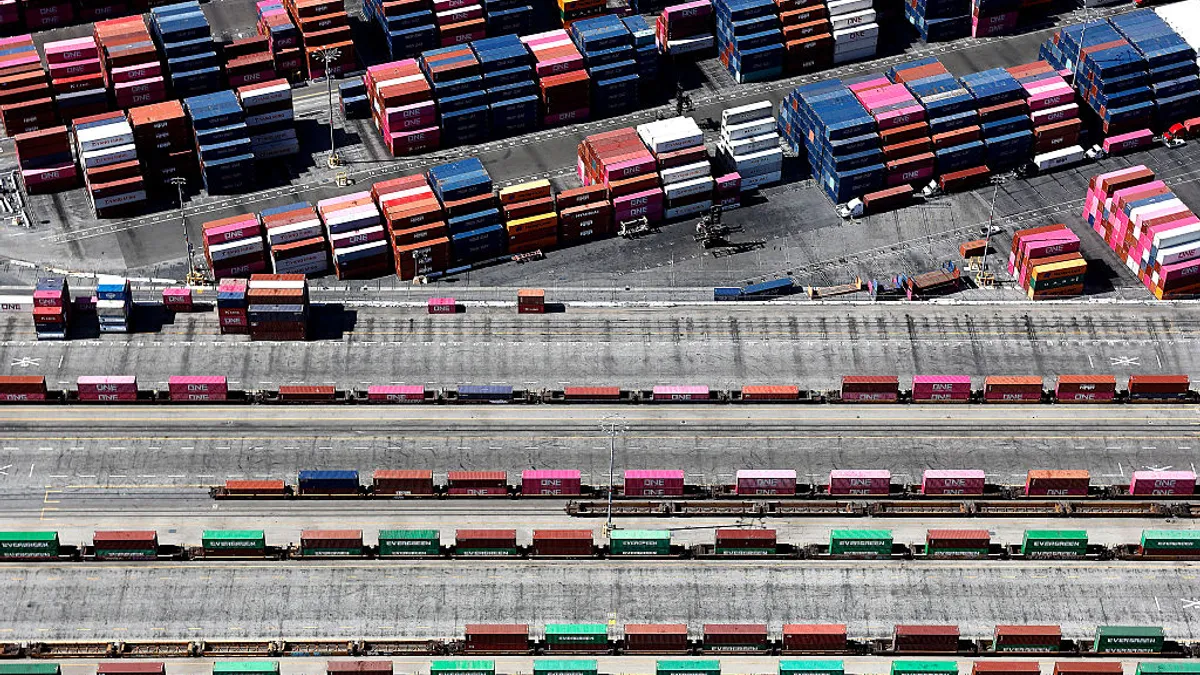

"Global supply chain logistics issues, including shipping delays and transport interruptions, have also created out-of-stocks in certain areas for Kim Crawford and Ruffino which are imported from New Zealand and Italy respectively," Newland said. "We believe these challenges are temporary and continue to improve, and we expect to refill retailer inventory in Q2."

Brown-Forman, the maker of Jack Daniel's, Woodford Reserve and Fords Gin, said its distributor and retail inventories are down compared to before the pandemic. CFO Jane Morreau said that the decrease is due to a confluence of transportation and logistics disruptions that include faltering service from rail and ocean carriers and lack of capacity in trucking markets and shipping containers, which are impacting inventory levels in the U.S. and abroad.

"We're at the mercy of the supply chain somewhat in this as things work out," Morreau said on a June earnings call. "We're working with our teams the best we can."

Diageo decided to work closely with its suppliers to shore up sourcing in the U.S., which CEO Ivan Menezes called its "largest and most profitable market" last year. To do so, the brand behind Ciroc, Crown Royal and Tanqueray shared its operating procedures with suppliers to help protect employees. It also launched its Diageo Supplier Service Hub to provide "one-stop shop" for facilitating work with suppliers, according to its 2021 Annual Report.

"Sourcing raw materials, such as glass and packaging ... led to industry shortages in the United States earlier this year. In working with our suppliers and partners to reduce disruption to their businesses and ours, we have provided support," the report reads.

Brown-Forman has experienced some shortages with the steel it uses to create hoops around its barrels. But the biggest woe has been with the company's lacking glass supply.

"The key ingredient that we've had some disruptions on is our glass supply. And that is certainly something that is really important to us and something that we are working closely with our supplier now ... and get that resolved," Morreau said.

Glass shortages have hit companies big and small, throwing yet another obstacle in the way of getting product from suppliers to retailers. Smaller brands especially have to pivot quickly in order to keep margins balanced and stay afloat while weathering supply disruptions or cost increases, typically owing to fewer resources and smaller networks than their larger competitors.

"I do know so many bars and restaurants had to reduce their inventories over the last year. And so, it became an advantage for established big brands to turn faster."

Lawson Whiting

CEO of Brown-Forman

Eda Rhyne Distillery — a small-batch spirits distillery — transitioned from importing glass bottles from Italy to securing its product from a domestic supplier when the price precipitously jumped to $67,000 for a shipment that before cost a fraction of the price. The Asheville, North Carolina, brand had to switch to buying clear glass bottles and dying them to produce the distinctive green color it's known for. But Owner Rett Murphy said the change, while more involved and more expensive than before, was necessary to secure bottles and cheaper than staying with its former bottlemaker.

And that's not the only material causing disruptions. Metal bottle caps that once cost $450 for 5,000 units and were available in a "matter of days" now goes for $1,600 and takes months to arrive, Murphy said.

Accumulating disruptions

On top of material shortages and cost increases, issues with moving product from distillery to warehouse to retailer adds to the obstacles companies have to overcome to fulfill orders.

The North Carolina Alcohol Beverage Control Commission recently acknowledged challenges with the state's liquor supply chain that covers the 171 ABC boards in the state. In an August monthly meeting, it called out its transition to a new contract for warehousing and its delivery services as pain points.

Murphy highlighted that the state's electronic system for placing and fulfilling orders is hampering the fulfillment process. A third-party system was brought in to update the existing portal, but half of the orders are being dropped and not reflecting accurate stock levels, he said. That translates into unfulfilled orders, which is happening to Murphy's distillery almost every day.

"LB&B had a fairly antiquated system before, but it worked," he said. Now, the stock statuses that Murphy sends are not matching what's reflected on the portal, preventing products from flowing to bars and restaurants.

Kim Wilkinson, the owner of Members Only Tasting Room and Social in Charlotte, is feeling the impact as it continues to be hard to secure brands that customers expect.

"It is disheartening with customers leaving to go to another place because of liquor outages," Wilkinson said. Bar favorites such as Hennessey and Patron, and specialty liquors like Uncle Nearest and Blanton's have been in limited supply, he said. And while the bar opened in 2020 merely weeks before the pandemic took hold of the country, Wilkinson has been in the industry for over a decade and has never seen this level of disruption.

Brown-Forman sees the predicament bars are in and intends to seize on the moment to create a competitive advantage. The goal is to get its product behind the bar over craft brands that aren't as equipped to produce and distribute supply fast.

"I do know so many bars and restaurants had to reduce their inventories over the last year. And so, it became an advantage for established big brands to turn faster," CEO Lawson Whiting said on a June earnings call. "We're going to go make sure that we get more than our fair share of that opportunity as things evolve over the next few months."

And Molson Coors' upcoming launch of an ultra-premium whiskey brand fits into this trend, as executives confirmed that the premiumization of brands is "here to stay" in its attempt to turnaround sales by cutting economic brands and going top shelf.

While a 2019 NC senate bill was passed, in part, to allow distilleries to directly ship orders to retailers and consumers, the reality of that has not come to pass, Murphy said. Control of that process was ceded to the state's ABC Commission and has not progressed to the point where Eda Rhyne is allowed to independently ship to customers, he explained. That ability could give smaller, in-state brands leverage to better compete against large companies like Brown-Forman and Molson Coors in getting bottles on bar shelves.

"No end in sight"

But there is at least one commonality across the board: There is no company, big or small, that seems to know when disruptions will stop and where.

"As we've seen over the course of the last 18 months around the pandemic, you often see some things where you get starts and stops and things improve in certain states and don't improve in other states," Constellation Brand's CEO William Newlands said in June. "I think it's going to vary ... quite a bit by state depending on the individual restrictions."

As states opened up bars and restaurants, the sudden demand strained liquor supply chains that had pivoted during the pandemic to prioritize private sales. And while shortages abound throughout the industry, in some states the issue is more pronounced than in others.

"The turnaround time used to be anywhere from 2 to 3 hours, now it's been almost 48 hours."

Hunter Thurston

Spirits buyer at The Crunkleton

When Thurston traveled to Arizona in July, he was shocked to see bar walls fully stocked in Phoenix, on a Friday night to boot. When he asked workers at Trevor's liquors and bartenders at Diego Pops about stockouts, they said there were basically no issues. Arizona is not an alcohol control state.

Similarly, right across the state line in South Carolina — which also doesn't regulate alcohol sales — Wilkinson said that stores have a much better selection than NC ABC stores only miles away. But commercial venues aren't allowed to even cross county lines to fulfill orders, let alone go to another state.

Thurston and Wilkinson keep hearing state officials say that current shortages are stemming from a combination of transportation delays, product stock-outs at distilleries, and labor shortages of drivers and workers at warehouses and stores.

In response to the challenges, Keva Walton, CEO for the Mecklenburg County ABC Board, said "our team is working extra hard to keep our stores stocked with the shipments we receive as soon as we receive them. We will continue to provide alternative spirit brands, where there might be a lower availability of preferred brands, when possible."

While changing liquor brands is an immediate option, long-term it can be more expensive.

"Over the course of a year, it adds up," Thurston said. The bar hasn't raised its drink prices yet due to higher liquor costs, but it has increased prices for food.

"We're all having to make the best of the situation … their intention isn't for us to not make money," Wilkinson said, referring to the state. But he does hope that NC considers to some extent privatizing liquor sales in the future to prevent this from happening again. For the here and now, relief is pending.

"There is no end in sight," he said.