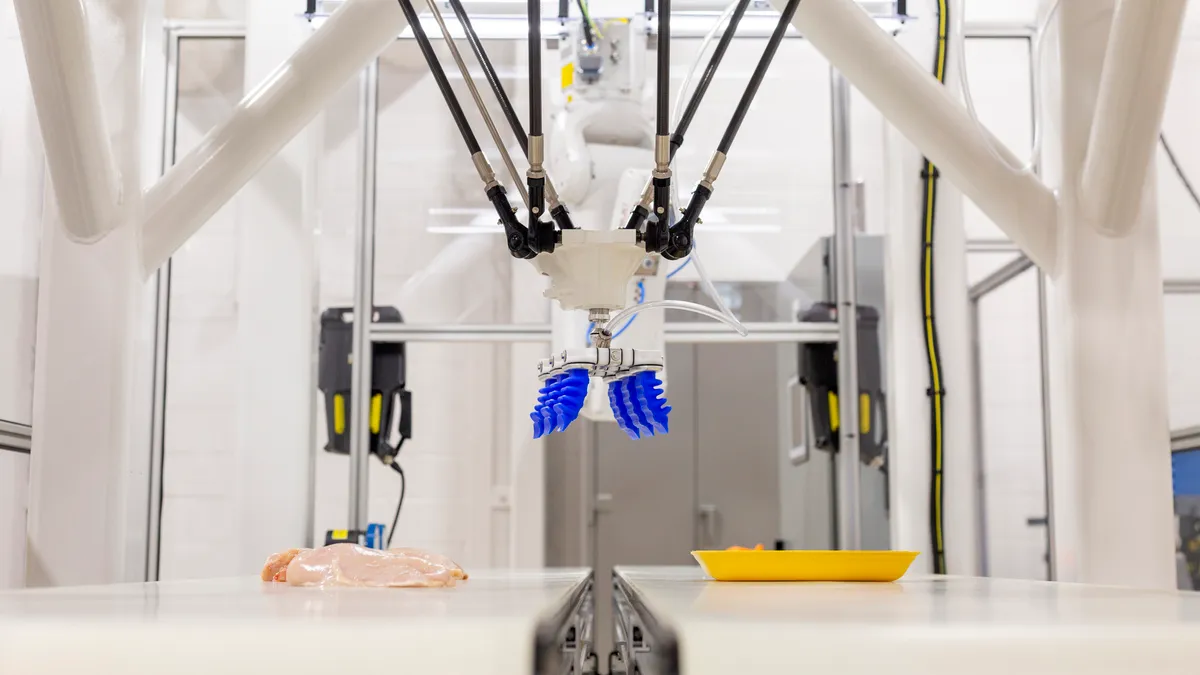

In one room, a conveyor belt that has a robotic arm with machine vision cameras and blue grippers swoops down to pick up chicken and places it in a tray pack. In another, an automated mobile robot forklift rolls around, guiding itself, and a giant yellow robotic crane picks up packages and wraps them to be shipped.

This new-age equipment can be found in the Tyson Manufacturing Automation Center's 26,000-square-foot facility in Springdale, Arkansas, that opened more than a year ago. With masks on, engineering directors Doug Foreman and Marty Linn led Food Dive on a tour of the center through the lens of a Facetime call.

Tyson Foods is one of many meat companies ramping up its automation strategy as the pandemic has emphasized safety concerns among its workforce.

Automating meat factories is costly. And carcasses come in varying sizes, so it can be difficult for robots to cut and work with all types accurately. But as the coronavirus ravaged meat plants, forcing many to temporarily shutter as thousands of workers got sick, more companies accelerated automation plans.

The pandemic has increased the pressure on Tyson's automation team, its top engineers said.

"The sense of urgency is higher… I think it's been known for some time that Tyson needed to have a way to enter into doing more and more automation, specifically robotic automation. But yes, like everybody else, the pandemic kind of opened up everybody's eyes,” Linn said.

Despite the challenges, Tyson, Smithfield, Cargill and JBS are looking into ways to incorporate more automation as they modernize their plants. Food Dive took tours, interviewed companies and spoke to experts about where these meat companies stand in that process and what a more robotic meat plant future could look like in the U.S.

Inside Tyson's automation center

In one of Tyson's innovation labs is a demonstration of a robot that uses a camera to sort beads by color. Encased in a glass box are red, yellow and green beads scattered all over. In under 30 seconds, a robotic crane with a camera is able to separate them by color into different cups.

Foreman, who has been with Tyson for 20 years, said that the compact demonstration shows what they are trying to integrate into their processes, where cameras not only see shapes but also color. That type of robotic camera could help detect defects on products, like a coloration that shouldn't be there, he said.

Foreman said Tyson's automation center is working on developing more with vision technology for its robots, "because if you can't see it, you're not going to be able to do anything with it." Vision technologies are developing at a rapid rate, he said.

"Cost obviously has come down significantly over the last number of years; there starts to become a point where it starts to make sense. Maybe 10 years ago, it would just be way too expensive; the technology wouldn't have been developed enough. But I'd say the whole vision side of things is really where a lot of our focus has got to be going forward," Foreman said.

Foreman and Linn walk to another room in the facility, which simulates a food production environment where the temperature can drop to 35 degrees-40 degrees.

"Really one of the keys for us being successful at doing automation is being able to fully test, fully vet the automation in the environment, and the type of conditions that we're going to subject it to,” said Linn, who previously worked as principal engineer of robotics at General Motors. "We can bring product in here as we need to process it. It really gives us an advantage to be able to use some of the advanced technologies, try those out in the environment without having to take it to the plant."

There's also a small workshop where they can cut, drill and weld. And in one innovation lab, opaque windows protect its intellectual property, but with the click of a button the windows clear.

Having a facility dedicated to automation also helped Tyson adjust to the needs during the pandemic. In one room at the robotics center is an infrared scanner that can be found at Tyson plants across the country. As meat companies raced to find ways to keep its workforce safe while the coronavirus spread, Tyson set up a testing facility at the automation center to evaluate what technology was needed and the best system to get accurate temperatures of workers. Afterward, Tyson installed infrared body temperature scanners at all of its plants.

"From San Francisco to New Jersey, we've had technicians dispatched to install these systems, and we did all of that in about eight weeks," Foreman said.

But even using its engineers and experts, it was a mad dash to get the process done.

"It was a lot of scrambling. We were jumping through hoops trying to get these systems and understand them, understand how to set them up, what the limitations were, and trying to get them into the plants as soon as possible, just to be able to help the team members," Linn said.

Walking around the center are Tyson workers who are training and getting hands-on interaction with robotics. Employees can come to the automation center and learn about the developments and how to operate them, the engineers said.

"There's a bit of a fear factor with robotics as you start to introduce those into facilities. And so anything we can do to try and get some familiarity to that comfort level with our team members, and dealing with robotics, and not being concerned about those things, and being confident in their ability to deal with those systems in our plant is a big part of getting started in this type of automation," Foreman said.

There are still limitations to automation. Foreman said it takes "a lot of trial and error" in developing robotics. But the engineers said they are looking to implement tools that help workers do their jobs more efficiently.

"Let people do the more value-added type of activities in our process," Foreman said. "Use robotics to do those difficult, dull and highly repetitive tasks. The robot can do that all day long and not fatigue or get distracted or have trouble getting through that process."

"Let people do the more value-added type of activities in our process. Use robotics to do those difficult, dull and highly repetitive tasks."

Doug Foreman

Director of Manufacturing Technology at Tyson Manufacturing Automation Center

Linn said at one plant, for example, robots instead of people set up corn dogs in a straight line so they can be put in the packaging correctly.

"That's a really great example of where some automation, robotic automation in this case, can help eliminate that kind of stressor for the team member to actually sit there and do that. Honestly, it's the kinds of jobs that people really don't want to do," Linn said.

Tyson has invested at least $500 million in technology and automation in the past three years and elevated leadership with experience in this area. Dean Banks, who has a background in technology, became CEO of Tyson last month.

"Tyson Foods and actually many of the Fortune 500 companies are in a pole position effectively to take advantage of these technological developments that we see very minimally utilized across corporate America,” Banks said at a recent Northwest Arkansas Technology Summit.

How other companies are planning for a robotic future

The world's largest meat processor, JBS, has been experimenting with more machine learning over the years and previously said it is putting part of its $1 billion capital expenditures toward automation this year.

"There's no question more automation is coming," JBS CEO Andre Nogueira said at The Wall Street Journal's Global Food Forum last month.

In 2015, JBS bought a controlling stake in Scott Technology, a robotics firm based in New Zealand. Andrew Arnold, director of meat processing at Scott Technology, said it is working closely with JBS on how the tech company may be able to help the meat processor automate more in the future.

"JBS is a shareholder in our company and so we've got a very strong relationship with JBS and it is an important part of our business," Arnold said.

"There's no question more automation is coming."

Andre Nogueira

CEO of JBS

Even before the coronavirus, the meat industry struggled with worker shortages in recent years, and the outbreak just exasperated those issues. Arnold said Scott has seen increased interest due to the pandemic.

"I would say probably the last two or three years, we've seen a lot of interest coming from all over the world," Arnold said. "There's definitely people out there looking at how they can fix the labor shortage problem."

Arnold said Scott has been developing technology in the meat industry for the last 20 years. Scott started with automating the lamb boning process and has a number of systems in the market now. It is currently in the process of expanding more of its automation to beef, pork and poultry, he said.

To automate the process, Arnold said, the company needs to scan each animal to account for different features, such as their number of ribs.

"The challenges are really around the variability of products. Every animal is different. You've got to design a system that can cater for that variation," Arnold said. "We're using advanced technology to understand where we need to cut and then cutting accordingly and making sure we cut accurately."

Meanwhile, Daniel Sullivan, media relations director at Cargill Protein and Animal Health, said in an email that the company is "embracing technology" across its supply chains. Sullivan said the company has been in Silicon Valley meetings with innovators nearly every month to make sure they have the latest insight.

"The future of protein will absolutely include automation. We've already seen these advances in grading, packing and plant logistics," Sullivan said. "The reality is producing animal protein means managing live animals that vary in size, weight and other dimensions that make automating the initial part of the supply chain complex. As we get closer to finished products, the opportunities for automation increase."

Smithfield Foods' 2019 sustainability report said that it is planning to invest tens of millions of dollars in robotics to automate production processes in its plants.

Howard Anderson, senior vice president and chief global engineer at Smithfield, said in an email that by 2050, Smithfield expects advanced robotics, AI and data analytics to be at "the forefront of modern manufacturing."

Already, Anderson said, Smithfield has a variety of automation deployed in its plants, like automatic rib pulling and cutting equipment that uses a 3D bone-in model before making specialized cuts based on length, width and thickness. Smithfield's facilities are also using new conveyor systems to move meat throughout the facility, which cuts down more than 50% of the forklift traffic.

"We envision a future where automation will impact the majority of tasks to the benefit of our employees, customers and consumers, but manual facets of facility operations will continue to be necessary."

Howard Anderson

Senior Vice President and Chief Global Engineer at Smithfield Foods

"The state-of-the-art equipment addresses employee safety by eliminating ergonomically hazardous tasks and reducing floor traffic. It also meets strict food safety guidelines, while increasing efficiencies for better product yields," Anderson said.

A 2018 report by Deloitte and The Manufacturing Institute found the U.S. could see a manufacturing labor shortage that would leave as much as 2.4 million roles unfilled by 2028. To prepare for this, Anderson said Smithfield has implemented a task force to accelerate its automation implementation and is investing in programs to attract the skills-based talent.

"We envision a future where automation will impact the majority of tasks to the benefit of our employees, customers and consumers, but manual facets of facility operations will continue to be necessary," Anderson said.

Challenges remain, but some countries are ahead of the game

There are already more mechanical solutions and technology integrated into plants. Wired reported that poultry production in the U.S. has gone from 3,000 chickens processed per hour in 1970 to 15,000 today using more technology.

But the next generation will have more robotics, said Shai Barbut, a professor in the Department of Food Science at the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada. Advanced automation can use a camera, machine vision or X-ray to locate where the joint is and send a knife to cut it, Barbut said.

More robotics have found different applications in the meat industry over the years, such as Robo Batcher, which uses a lifting arm and moves meat cuts from a conveyor belt to arrange them on trays, Barbut wrote in his book, "The Science of Poultry and Meat Processing."

It can be difficult to develop advanced robotic technology, though. Barbut said in the automotive industry there are identical parts — all the screws are exactly the same size, for example — so it's easier for robots to deal with equal sizes. However, biological variations, such as large wings and small wings, can cause problems, and it can be difficult to develop smarter machines to deal with that.

But more advanced innovation already exists and is being used in other parts of the world.

For example, in Denmark robots do most of the work, such as measuring hogs with an infrared laser robot, at Danish Crown's Horsens facility, one of the largest international pig slaughterhouses. The company told Wired that its automation helped it avoid any major coronavirus outbreaks early on in the pandemic, but the plant did see an increase in positive cases last month.

And more is in the works. At a trade show in Germany, Barbut watched a presentation of beef carcasses hanging upside down with six cameras around it, taking pictures to map its body and build a 3D structure, similar to an MRI machine. By doing this, Barbut said, they can optimize cutting the meat to know where the bones are located and can send robotic knives with very high precision.

"I've been visiting some plants in Europe where they're almost fully automated in terms of poultry processing. Here in North America, most are not, but it's just a matter of investment. There's a lot of equipment that is already on the market, but obviously it's expensive. But I think that we'll see more and more companies moving toward this," he said.

Even before the pandemic, meat processing has long been considered a dangerous job. But because some meat packing plants temporarily closed as many workers were infected with coronavirus, Barbut said there is "a very significant extra push to move to more automation."

"The future is basically to replace more people on the processing line. So in the past, you'd have people doing evisceration of poultry or red meat animals. Today robots can do those same tasks because of the fast development of machine vision and other sensors," Barbut said.

"The future is basically to replace more people on the processing line."

Shai Barbut

Professor in the Department of Food Science at University of Guelph

So, will automation mean less jobs? Research from Massachusetts Institute of Technology found that from 1990 to 2007, one robot per 1,000 workers decreased the national employment-to-population ratio by roughly 0.2%, which means that on average each robot replaced about 3.3 workers nationally.

Other studies have shown automation has the potential to reduce costs. Technavio analysts predicted that replacing humans with robots could lead to a 22% increase in cost savings by 2025. Those savings could be shifted to pay.

Some meatpackers, such as Tyson, have increased wages in recent years to help attract and retain workers. The U.S. Department of Labor reported that meatpacking and processing workers earn on average between $13.50 and $14.70 per hour.

Barbut said that there will likely be less people in meat processing plants, but the workers will need to be highly skilled to work the robots, which would mean replacing some of the lower paying jobs with higher paying ones.

“If you build a new plant that costs $50 million, you want it to work most or all of the time, but finding people to work three shifts, night shifts and holidays is a challenging task," Barbut said. "Robots can work seven days a week, no coffee breaks, no social issues."