Even as the coronavirus pandemic continues to deliver legions of consumers eager to buy groceries online, it is putting a focus on the multiple challenges grocers face in determining the best ways to fulfill those growing orders.

Across the industry, executives are looking at creating dedicated fulfillment facilities, known as microfulfillment centers or MFCs, at or near individual supermarkets to improve efficiency and save money in running their e-commerce operations.

The interest in MFCs, which typically include automated equipment to assemble and pack orders, has grown because of the surge in e-commerce orders that has cascaded across the grocery industry this year. But while transferring picking and packing tasks from store aisles to facilities expressly designed to handle them might seem like an obvious move, deciding when and how to deploy this strategy isn’t as straightforward as it might seem, according to e-commerce experts.

MFCs aren't the only answer

“I believe the MFC will definitely be a part of the solution, but I do not see a world where a hundred percent of volume for grocery e-commerce goes exclusively through MFCs,” said Narayan Iyengar, a former e-commerce executive at Albertsons who is now an investor and grocery industry advisor. “You will have store pick, you will have dark stores, you will have the central fulfillment sites taking on certain subscription-type fulfillment, and then you have MFCs. It will be a constellation of those things that would have to work together to make this thing work.”

MFCs have been attracting attention from grocers because of their ability to mechanize the tedious and time-consuming process of grabbing items and packing orders. A number of automation companies, such as Alert Innovation, AutoStore and Takeoff Technologies, have risen to the occasion with an array of robotic systems that can take on many of the order-assembly tasks humans otherwise have to handle, and at a localized scale that's much smaller than traditional warehouse fulfillment.

Despite the excitement swirling around MFCs, it is important for grocers to consider whether they would be better off establishing a dedicated in-store zone where human pickers can assemble orders instead, experts said. In some cases, a dedicated picking area in back of a store may be all it takes to increase efficiency, because such an arrangement can remove pickers from store aisles, where they have to compete with customers for items and space to maneuver carts.

It all comes down to the amount of e-business activity a store expects to handle, said Jordan Berke, a former Walmart executive and e-commerce expert who runs Tomorrow Retail Consulting. A location that sees only 20 orders per day can probably get by with store staff manually collecting and packing items for online customers, while a store with a few hundred e-commerce orders might want to dedicate picking space for humans to deal with the fastest-moving products, he said.

“The equipment is real simple. It’s shelves,” Berke said, adding that stores can also deploy handheld devices and other technology to help pickers find items more quickly.

Sarah McMullin, director of product, retail, for Tecsys, a firm that helps retailers implement warehouse automation strategies, said grocers can improve their fulfillment capabilities regardless of whether or not they opt to invest in automation to fulfill orders at the store level. She recommended that grocers look at ways to increase visibility into where products are in the supply chain, and noted that simply deploying better equipment to human workers to help them locate products and plan their order-picking can make a big difference.

"People that are working within the stores are often temporary workers or they've just come on. And so [systems] have to be super easy and super simple for people to be able to just to put together the orders really quickly and fast," McMullin said.

Balancing volume, costs and capabilities

Once a store sees orders really start to increase, however, and modeling shows those orders will continue to increase, exploring MFCs to handle picking tasks automatically starts to make sense, Berke said. “It’s about volume. If you’ve got 50 orders a day in a store, don’t come talk to me about a pick zone or microfulfillment. If you’ve got 1,000 orders a day in the store, don’t try to pick those from the store.”

The costs to build an MFC can add up quickly. A single MFC that can handle 5,000 orders per week can carry a price tag of between $8 million and $10 million after expenses for site preparation, construction, equipment software-integration and other expenses are taken into account, said Marc Wulfraat, a supply chain expert who helps food retailers design fulfillment systems. Retrofitting a store backroom to optimize space for an MFC can oftentimes be the largest expense, Iyengar said.

Beyond the hefty upfront costs, retailers that invest in MFCs could also find that the trajectory of their e-commerce business diverges from their predictions, leaving them with pricey infrastructure that doesn’t meet their needs down the road. Given that the heightened consumer interest in buying grocery orders that has been driven by the pandemic may well subside, retailers need to be conscious of the risks of investing in infrastructure they may not need.

“It’s possible that retailers say customers aren't buying as much digitally as we [thought] they might, and these microfulfillment centers are more expensive and less efficient than we were hoping they would be,” said Jason Goldberg, a retail analyst who is chief commerce strategy officer Publicis, an advertising firm.

Another risk is that MFC technology is progressing quickly, which means equipment put in today may turn out to be obsolete sooner than expected.

“I’ve got many stories from Walmart and others, where we automated early and had to basically scrap the automation because we have a business that’s rapidly evolving. You [may] find that your design and your automation doesn't apply a year after you’re done with it," said Berke.

“The automation engine is designed to produce x output. And that's all you're going to get from it."

Marc Wulfraat

President and founder of MWPVL International

In addition, once an automation system is put in, expanding or decreasing its capacity is difficult, said Wulfraat, who is president and founder of MWPVL International, a supply chain consultancy.

“The thing about automation, and what people lose sight of, is it looks great when you see the videos, but if something like COVID comes along where the volumes exceed what you planned on, you can't throw more bodies at the problem,” Wulfraat said. “The automation engine is designed to produce x output. And that's all you're going to get from it.”

Generating a ROI in a MFC can be complicated by the fact that automation technology designed for grocery settings has multiple limitations that can make it less than ideal, Wulfraat said.

Among the challenges is that MFCs generally are intended to handle only a subset of the items a typical store might carry, which means that workers often have to manually retrieve less-popular products the MFC doesn't have on hand when customers request them.

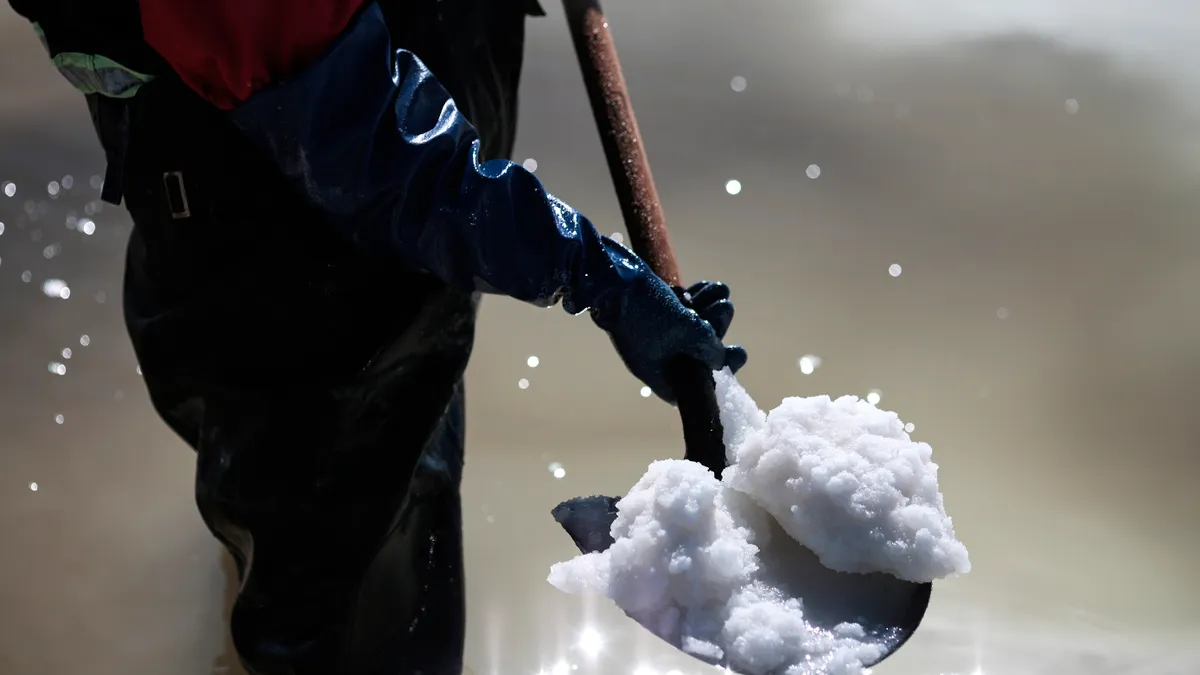

Wulfraat said an added issue is that the equipment used in MFCs is not designed to handle items that need to be weighed and may need to be handled delicately, like loose produce. Oversize items like toilet paper and bags of pet food are also challenging for MFCs. Meat and other items that can leak are problematic, as well.

"People usually don't put that in the MFC because you have the risk of blood dripping and contamination inside the totes," Wulfraat said.

“In a lot of cases where MFCs are active today, the retailer is trying to get 50% of the order line activity from the automation system, and the other 50% has to come out of the more manual approach either from the store or from manual operation adjacent to the automation system,” Wulfraat said.

Measuring current and future capabilities

In determining if and where to build MFCs, Iyengar said retailers need to look primarily for areas with concentrated order volume. Many grocers are seeing high overall volume due to the pandemic, he said, but if that demand is spread out over a wide geographic area as opposed to dense urban and suburban markets that ideally have multiple stores in them, the economics will be challenging.

Many grocers are weighing whether to build standalone MFCs or to add them to their current stores, either by erecting them in backrooms or bolting on a separate facility. Iyengar said both models have their own advantages but the less risky investment is to build them at the stores, because the systems can flow into existing delivery routes and store management operations.

Iyengar said it's also paramount that retailers perform detailed due diligence on MFC vendors to determine not just their current capabilities, but also their ability to evolve. Grocers should provide vendors with the fulfillment metrics they want to achieve, and check the system's order throughput both in terms of items filled and baskets assembled. MFC systems can quickly retrieve products, he said, but inspecting software systems to see how they marry assortments from automation and from manual pick is crucial.

"How many items you pick per minute is one element to it, but how quickly can you turn a basket around is much more important," Iyengar said.

Iyengar recommends grocers test with two or more MFC vendors, which can be more expensive but also allows for a close comparison of metrics. Retailers, he said, will also want to vet MFC vendors according to their ability to adapt and plug in new technologies in the coming years, noting that innovations like robotic picking arms loom on the horizon.

"You want a platform that will scale with you with advances in technology, but at the same time you want something that is stable enough that you don't need to have a full time mechanic on the ground to make this thing work every day," Iyengar said.

Even as they exercise caution, though, grocers should not underestimate the cost-savings they can potentially realize from installing an MFC, said Andrew Benzinger, who manages relationships with grocers for AutoStore, which is working with H-E-B to install MFCs for the Texas supermarket chain.

“Over [time], you can pay for the automation and have significantly more margin to work with, because you’re taking up less space and you’re using fewer people to serve your customer,” he said.

Curt Avallone, a veteran grocery executive who is chief business officer of MFC supplier Takeoff Technologies, which has worked with supermarket companies including Ahold Delhaize, Albertsons, ShopRite and Sedano’s, said the sweet spot for microfulfillment lies in using automation and human labor in tandem while adapting both to market conditions at individual stores.

MFCs can be optimized to handle just the items a grocers sells the most of, which can enable a busy enough store to realize the kinds of productivity gains a centralized warehouse can deliver while remaining close to the customer, he said.

"Where a microfulfillment center seems to finally be finding its niche is that you can put 14,000 or 15,000 items in a small area, and pick at the rate of the really large facilities, sometimes even better than those facilities," said Avallone. "In reality, the average customer only purchases 340 unique items a year from supermarkets that offer them 40,000."

As the automation systems used in MFCs get more capable, reliable and affordable, deploying them will become increasingly practical, said John Lert, CEO and founder of Alert Innovation. Alert is working with Walmart to develop robotic fulfillment technology and has built a 20,000-square-foot facility inside a Walmart store in Salem, New Hampshire, that uses self-guided carts to assemble grocery orders.

According to Lert, Alert’s goal is to make robots financially viable even for smaller grocery stores that today can’t justify the expense of automation.

“When you talk about automation technology, you'll hear suppliers talking about scale. And usually what that means is it's scalable up,” Lert said. “The challenge here is scaling down, to be able to create an automation solution that is low enough in cost and can go into a small space, so that you can actually deliver an ROI at low volumes, and do it efficiently.”

Jeff Wells contributed reporting to this story.