WannaCry may have set the stage last year, but Nyetya stole the show ... and up to $300 million of Maersk's money.

The wiper, disguised as a ransomware, was "deployed through software update systems for a tax software used by more than 80% of companies in Ukraine," according to a Cisco security report. Nyetya, also known as NotPetya, went on to infect more than one million computers.

A month before Nyetya reared its ugly head, WannaCry served as the "entry level vehicle," said Franc Artes, architect, Security Business Group at Cisco, in an interview with CIO Dive. Nyetya just "followed the exact evolution" with self-propagating properties that can go undetected.

Still, WannaCry and Nyetya were both supply chain attacks and Nyetya was able to disrupt supply chain giant Maersk.

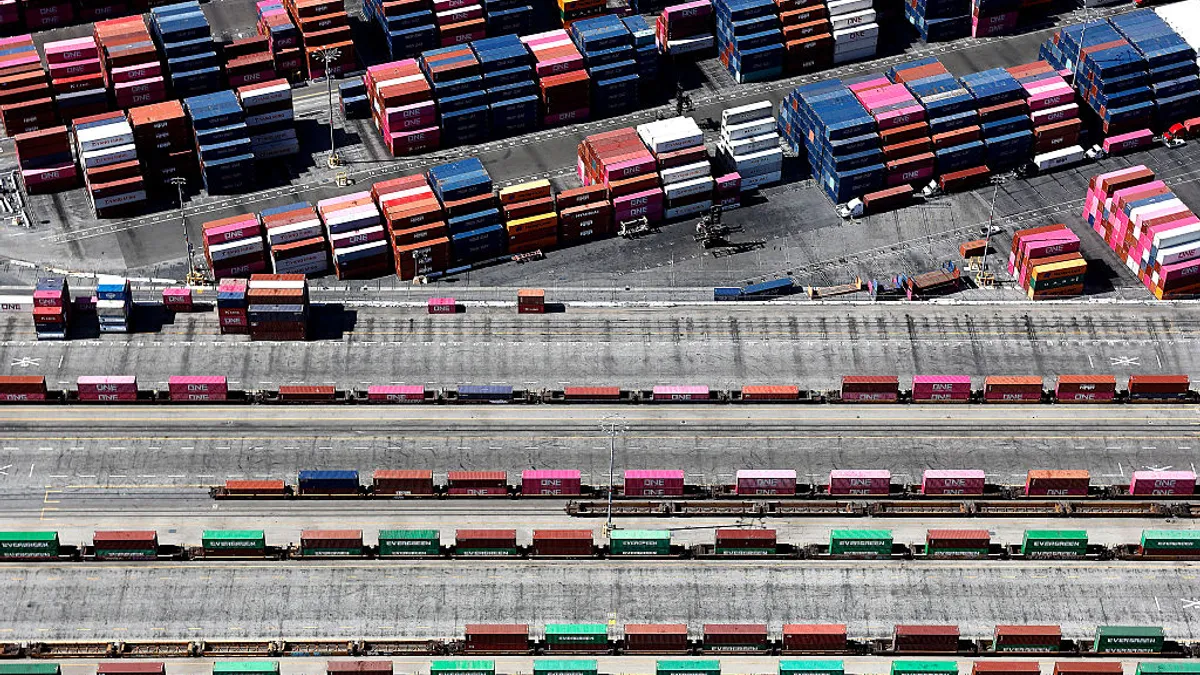

Nyetya impacted 76 of the shipping company's ports in key locations such as Spain, Los Angeles and the Netherlands. As a result, employees were forced to perform manual methods of operation, slowing down all processes.

Two weeks after the attack, the company was unable to follow service contract rules, which negatively impacted relationships with investors and shippers. The attack occurred in late June and stalled various international operations for Maersk through mid-August.

Because systems were offline, the company lost 2.5% in Maersk Line volumes, but faced a 3.9% uptick in fixed bunker prices, as well as increased desert times, to help terminal cost, and positioning and SG&A costs, according to CEO Soren Skou, speaking during a November earnings call.

Publicly, Maersk's recovery appeared slow and concerning. However, behind the scenes, the shipping giant pulled off a feat of "herculean resilience," said Charlie Burns, principal analyst at ISG, in an interview with CIO Dive.

In just 10 days, Maersk "reinstall[ed] an entire infrastructure," said Jim Hagemann Snabe, chairman of Maersk, speaking at the World Economic Forum in January. The company worked to reinstall more than 4,000 servers, 45,000 PCs and 2,500 applications.

Any other company most likely would have taken about six months to have matched the same kind of overhaul, according to Snabe.

The average recovery process of most major organizations take more than 10 days because "they're not designed for a total infrastructure rebuild," according to Burns.

To put it in perspective

Traditional recovery processes are made for replacing a single server, a workload that has between 10 to 20 severs, or a single data center, according to Burns.

Maersk was operating for 10 days without reliable IT and performed 80% of volume manually. In addition to keeping the lights on, Maersk overhauled its infrastructure basics, according to Snabe. Maersk declined to comment further on the overhaul.

That is too much to ask for an organization with very little direction as to how to approach that kind of process. While it is unlikely Maersk had such a plan already in place, they still "glued the pieces back together," said Burns. But the pieces are "more elusive than you might think."

For example, rebuilding a server begins with reinstalling the "image of the server," or the operating system, virtualization software, middleware such as database managers, utilities, languages and all the other stuff that "runs behind the scenes," according to Burns.

Then an organization would have to restore the database by using the most recent backup on memory. Depending on an organization's frequency of backups, the longer it takes to restore the database. Following that, organizations then need to "run the transactions that were executed against that database since the last backup," said Burns.

But that whole process needs to be repeated for every database a company has.

In the days after the attack, Maersk worked to synchronize its databases to communicate and exchange data while performing some operations manually all through the duration of the down databases. The transactions that were taken manually had to be input back into the databases.

The '90s called and it wants its malware back

Every cybersecurity expert has heard this bedtime story: Nyetya followed the lead of WannaCry with its self-propagating characteristics. And while most experts agree that there was no definitive way to completely thwart an attack like Nyeta, the wiper's fundamentals are known to be tools of hackers.

"This is the 1990s calling and they want their technology back," said Artes. Wormability is an old trick hackers are using in new ways, thus allowing Nyetya's wormability to leave its mark on the maturing nature of cyberattacks. Ultimately, anyone willing to work in a "maleficent manner is always quite creative," said Artes.

The similarity between WannaCry and Nyetya also falls on the negligent approach to patching. For example, hackers leveraging the EternalBlue exploit is nothing new.

However, with Nyetya, a "vast majority of the propagation occurred because of the password dumping," said Charles Carmakal, VP at Mandiant, in an interview with CIO Dive.

Because credentials are stored in the memory of a computer, an infected computer allowed the malicious code to extract the credentials from the computer that was logged into and attempted to use the same credentials on other systems in a corporation's networks.

Nyetya only turned to EternalBlue when "grabbing passwords" wasn't granting access, according to Carmakal.

How to prepare for the next Nyetya

Maersk most likely "had pretty good security, but not state of the art security," said Burns. But what was seen in Maersk is fairly common: cybersecurity protocols are trailing the attack vectors of hackers.

To survive a destruction of operations as Maersk did, review processes for systems become integral. This helps a company understand how quickly it can recognize a threat and test its response time.

Due to the complex nature of emerging cyberthreats, roughly 3,600 companies rely on outsourcing incident response but shortcomings arise when a contractor has no experience with a company prior to an attack, according to Artes.

Contractors need to understand a company's system, methodologies, and service level agreements, according to Artes. Companies need to ask, "at what point do I call you and how much can you augment?"

But before a portion of the budget is allocated to contractors, companies need to return to the basics.

Malicious emails cost about $5.5 billion internationally, which only highlights how ignorance tends to seep into cyber practices despite best efforts. Basic employee training is unavoidable. For example, not opening an attachment to an email an employee wasn't expecting is a good start.

Until an organization faces an overhaul as complex as Maersk's, companies will most likely continue to "[defend] today from what happened yesterday," according to Artes.