Jessica Darby is an assistant professor of supply chain management at Auburn University’s Harbert College of Business. Andrew Balthrop is a research associate for the University of Arkansas' Supply Chain Management Research Center. Opinions are the authors’ own.

Disruptions in the ocean freight market have created a tsunami of concerns that have led to new legislation, waves of new rules, and a steady current of accusations about collusion. The data, however, suggest that there is more competition on the waters than policymakers want to admit.

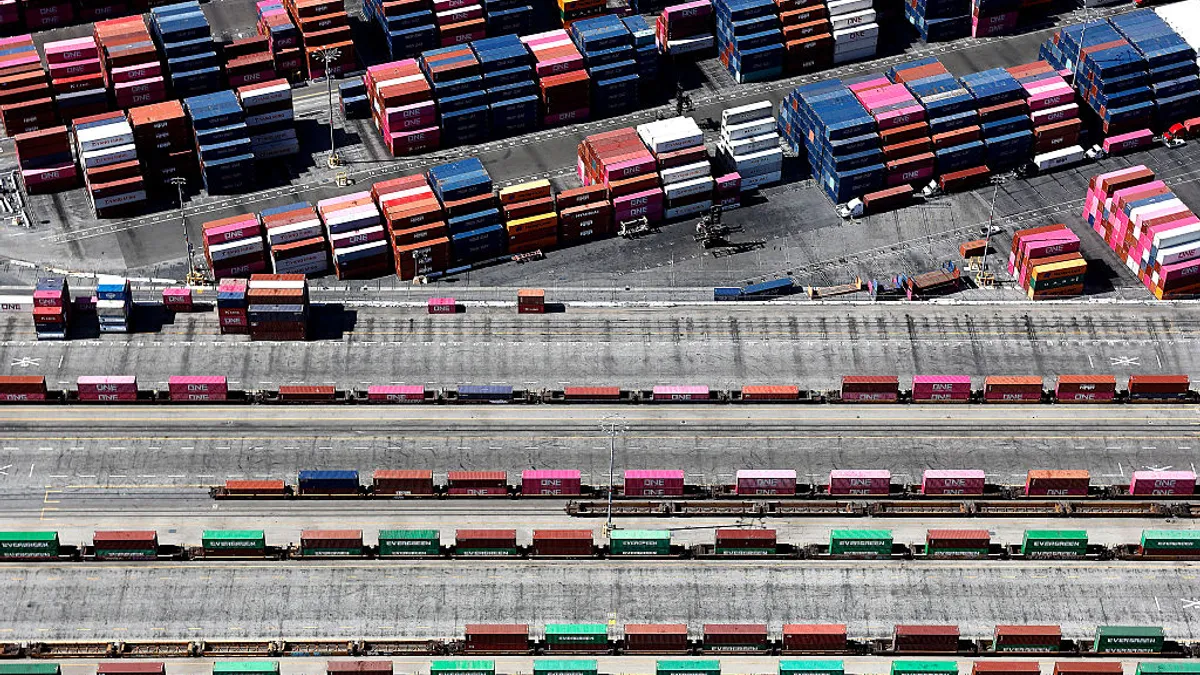

Since the onset of COVID-19, the market’s behavior has been guided by unprecedented demand shocks and disruptions, not collusive behavior by carriers. Increases in total volume—combined with fluctuations in volume due to pandemic-related closures and reopenings—produced deep market turmoil and caused rates to skyrocket.

Yet, much of the repsonse to ocean shipping congestion from the White House and Congress has largely centered around the consensus that the market remains anticompetitive. After many U.S. shippers complained that their shipments were abandoned, the White House accused ocean carriers of price gouging and announced that the Department of Justice and the Federal Maritime Commission would combine forces to enforce antitrust laws pertaining to ocean carriers.

“Three global alliances, made up entirely of foreign companies, control almost all of ocean freight shipping,” the statement said, “giving them power to raise prices for American businesses and consumers, while threatening our national security and economic competitiveness.”

The imbalance also led Congress to pass the Ocean Shipping Reform Act of 2022, which promised to “crack down on foreign-owned carriers’ unfair shipping price hikes, strengthen maritime supply chain, and reduce costs for consumers.”

While shippers were understandably furious when their contracts were not honored by carriers, ocean shipping companies were simply responding to market signals. Eastbound containers across the Pacific were worth significantly more than those headed west, so carriers would return empty containers to Asia as quickly as possible to be reloaded with higher-revenue cargo.

Even the FMC, which is responsible for regulating ocean carriers, recognized that there is no collusion within the industry and that OSRA was solving for anti-competitive behaviors that did not actually exist.

“Though there have been charges of illegal activity or concerns of market concentration driving increased ocean freight costs,” the report said, “the Fact Finding Officer’s assessment is that our transpacific market is not concentrated and that the increased rates in that market are a result of an extreme spike of consumer demand in the United States that overwhelmed the supply of ship capacity.”

The report went on to add: “We have, to date, observed no indication that current prices for liner shipping are a result of collusive or illegal conduct on the part of ocean carriers in our markets.”

Information empowers

Overall, the evidence suggests that the ocean freight market indeed is competitive. But, opportunities remain to further enhance competition and level the playing field for U.S. shippers—without heavy-handed enforcement from the FMC.

Aside from repealing the Jones Act, the best way to enhance competition is to publicly provide information on freight rates and volumes, as well as detention and demurrage fees. More information about freight rates and flows would allow shippers and carriers to rationally consider alternative plans and deploy assets where they are most needed (or most cost efficient). And, it would help disarm entrenched carriers whose size comes with informational advantages.

Unfortunately, information disclosure is a constant battle in the ocean freight market, in part because the previous Ocean Shipping Reform Act (1998) made contracts confidential. In this regard, OSRA 2022 actually took an important step forward by mandating more information disclosure, such as requiring ocean carriers to report the number of empty containers being transported, authorizing the Bureau of Transportation Statistics to collect data on dwell times for chassis, and providing the FMC with temporary emergency authority to collect data during times of emergency congestion.

Specifically, the FMC can issue an emergency order requiring any ocean common carrier or marine terminal operator to share information on cargo throughput and availability directly with shippers, rail carriers or motor carriers. However, the agency recently declared the temporary emergency order was no longer necessary, which once again hides important information deeper than Davy Jones’ locker.

This sort of transparency is not just necessary during times of emergency, it would also help alleviate congestion at terminals and improve the predictability of available containers. It additionally would help ocean carriers more accurately forecast demand and therefore provide necessary capacity.

While shippers were frustrated and often felt powerless in the early stages of COVID-19, OSRA’s added bureaucracy will not serve them or consumers well over the long haul. Information, however, empowers everyone—shippers, consumers, carriers, and even regulators. Data disclosure can enhance competition and allow for more accurate assessments so that anti-competitive behaviors can be addressed only when they are real, not simply perceived.