While alternative fuels, including electric vehicles, are gaining ground, the need for oil won’t be going away for a while. In addition to transportation fuels, petroleum products are used for heating, for electricity generation, asphalt and road oil, and for making the chemicals, plastics and synthetic materials that are in so many of our everyday products.

When it comes to transporting petroleum —whether crude or refined —there are several options, including pipelines, ships and barges, trucks and rail. Each mode has its own risks and rewards.

Pipelines are common but carry risks

Pipelines are the most prolific, handling about 70% of crude. There are more than 70,000 miles of crude oil pipelines in the United States alone, moving approximately 1 billion gallons of oil from field to refinery daily.

Once built, the pipelines are a very cost-effective way to move the product; however, they don’t come without risk. In the network of pipelines, most of which are underground, oil is moved at pressures of about 1,000 pounds per square inch. Aging or corroded pipes are apt to leak. How much? According to the USTA’s Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration around 9 million gallons of crude has spilled in the U.S. since 2010.

Sometimes pipelines carry multiple products, including crude and refined petroleum, natural gas and biofuels. Even raw crude oil, which is not typically volatile, can be hazardous because chemicals are added to make it flow more easily through the pipe.

Other ships have to steam out of the way to allow cleanup, or they’ll just make it worse.

Bob Gernon

VP Logistics, Maine Pointe

Last November, 210,000 gallons leaked from the 2,687-mile Keystone Pipeline system into a South Dakota field. In this case, the spill was contained quickly, but the risk to humans, animals and vegetation is there.

Spills that reach bodies of water can be devastating. In 2010, 843,000 gallons of crude leaked into Michigan’s Talmadge Creek and flowed into the Kalamazoo River. The largest inland oil spill in U.S. history, it eventually was contained more than 37 miles downstream from the site of the spill. The cleanup and restoration of the Kalamazoo River cost the pipeline company $1.21 billion.

The environmental cleanup is just one element of a pipeline leak, says Bob Gernon, VP Logistics at Maine Pointe, a Boston-based management consulting company. A 2016 pipeline rupture near Birmingham, Alabama, caused significant problems.

“There were difficulties getting gasoline to the greater Atlanta area," Gernon explained. "They had to identify the leak, get to it and shut it off. It took 10 days to clean up and get back in business. Thousands and thousands of people were inconvenienced because many gas stations were out, and those that did have gasoline raised their prices."

When a tanker springs a leak

To move the oil longer distances, say from the Middle East, requires maritime transportation. One tanker can hold 2 million barrels, equivalent to 84 million gallons of gasoline. Also used afloat, but for much shorter distances —typically 100 to 300 miles up to around 2,000 miles —and calmer waters, are barges. Propelled by tugboats, they can carry 10,000 barrels.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), oil spills from transport tankers only account for about 7.7% of oil in the ocean. However, when there is a spill, marine life will suffer. Ingestion can be fatal, and oil-soaked birds lose their ability to fly. Oil spills in open water can contaminate the food chain at the lowest levels and work its way up to the larger animals.

The 1989 Exxon Valdez incident — where a tanker ran aground in Prince William Sound, Alaska, and spilled 10.8 million gallons of crude into a pristine area — is infamous for that reason. The environmental impact was devastating, fouling a thousand miles of coastline and killing hundreds of thousands of animals. Cleanup took years and Exxon paid billions in costs and fines.

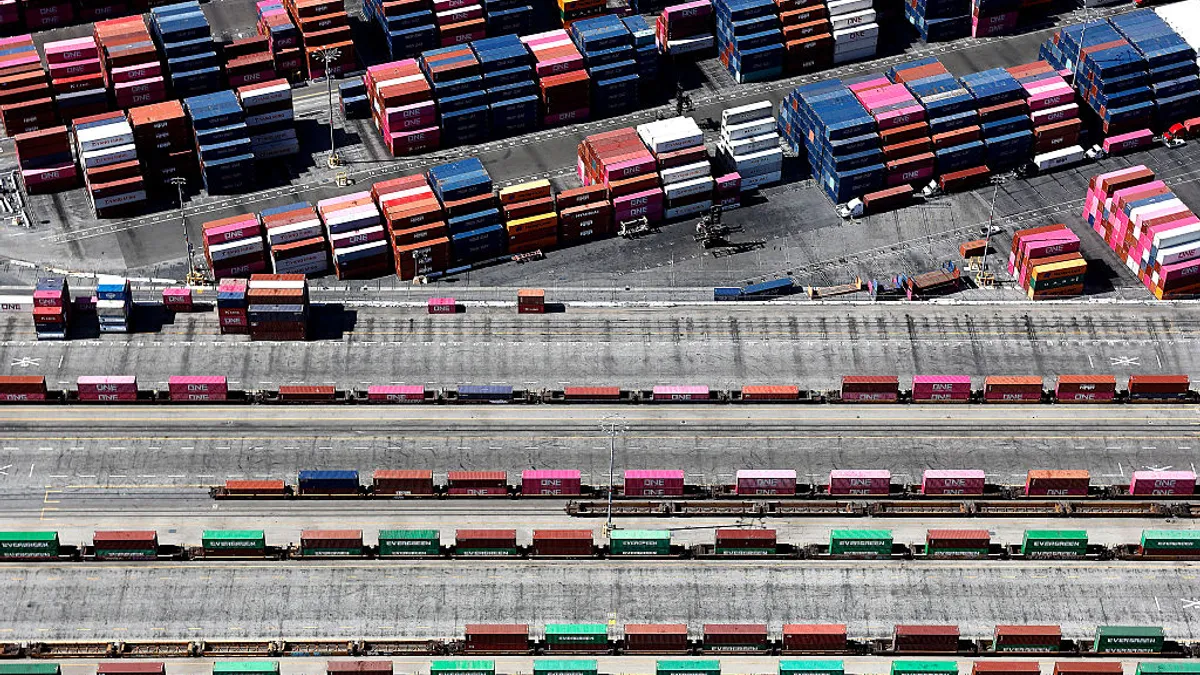

But what happens when there is a spill at sea in a highly dense international steamship corridor? "Other ships have to steam out of the way to allow cleanup, or they’ll just make it worse," Gernon points out. That throws off timing and schedules that can affect ports, unloading processes and onshore transportation to destinations.

In port, Gernon says, vessels have to be repositioned to alternate ports, if that’s possible. If not, they might have to wait 60 to 90 days to finally unload. “You have the cost of those vessels, lost utilization, lost capacity,” he says, adding that, quite often, the oil was meant for just-in-time delivery.

Who’s driving the oil around?

Trucks can carry about 200 barrels (9,000 gallons). They’re used primarily for moving refined fuel to distribution plants or gas stations, generally not exceeding around 50 miles. There are nowhere near enough trucks or drivers to move the millions of barrels of crude needed daily.

Trucking companies and 3PLs are striving to meet the growing demand for drivers. That shortage is spilling over into the oil & gas industry and its repercussions are evident.

One clear example is in the Permian Basin in West Texas. Permian has been pumping out oil since the first well produced there in 1920. After weathering the oil bust of 1998-99, when operators lost $2.8 billion in revenue, things have been on an upturn, producing more than 1 million barrels a day, according to the University of Texas Permian Basin. (The basin also produces almost 4 billion cubic feet of natural gas daily.)

Last year, Permian production hit 815 million barrels, easily exceeding the previous record of 790 million barrels set in 1973, business research firm IHS Markit said in a report.

Supply chain needs to play a critical pivotal role and understand the best and worst situations, develop contingencies.

Bob Gernon

VP Logistics, Maine Pointe

As oil prices creep up and production booms, companies in the Permian Basin are looking for drivers. Many who were dismissed following the 2014 oil price crash have decided not to return, choosing something steady, rather than the boom-or-bust oil industry. The producers also are offering less pay than four years ago.

Willie Taylor, CEO of the Permian Basin Workforce Board in Midland, Texas, told Bloomberg that companies will need to double their workforce to about 6,000 drivers to meet the expected need.

“The ability to physically operate more trucks is not there,” says Maine Pointe’s Gernon. “The economy heated up and drivers found higher paying jobs that had them home at night.” Another roadblock, he says, is passing the scrutiny of background checks. “Plus, (Electronic Driver Logs) make it difficult for the driver to keep 2 or 3 logbooks going to satisfy driver hours of service.”

Supply chains positioned to act

There have been regulatory issues that help. Following Exxon Valdez, for example, double-hulled vessels became mandatory for oil tankers built in the United States. And the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, or MARPOL, Convention made it mandatory for tankers of 5,000 dead weight tonnage (dwt) or more to be fitted with double hulls.

But regulatory changes can’t account for everything. “Supply chain needs to play a critical pivotal role and understand the best and worst situations, develop contingencies and have them agreed to” by all parties involved, Gernon said.

Some questions to ask: Who’s responsible? What steps should be taken? How long should it take? What does it cost?

Doing what worked in the past won’t do it, Gernon says. “Somebody has to have the depth and scope to understand what is happening globally and get into position to act.”

Correction: A previous version of this article misstated the number of barrels a truck can carry.