Everyone, it seems, is eating healthy today. The organic food market is growing and changing the way people eat, which means 3PLs and other links in the supply chain are growing and changing along with it.

C.H. Robinson, for example, created a unit for just that reason, building year-round solutions for a wider range of categories, including organic, according to Michael Castagnetto, vice president of global sourcing at Robinson Fresh, a business brand of C.H. Robinson, that markets and distributes fresh produce in both conventional and organic varieties.

“We have had to build organic expertise within our business for all verticals, as well as complement our dominant categories with organic experts to be able to supply both conventional and organic purchases for our customers,” Castagnetto said.

But as the organic market grows, the risks compound: according to a Washington Post investigation, 36 million pounds of soybeans were falsely marked as USDA Organic in May.

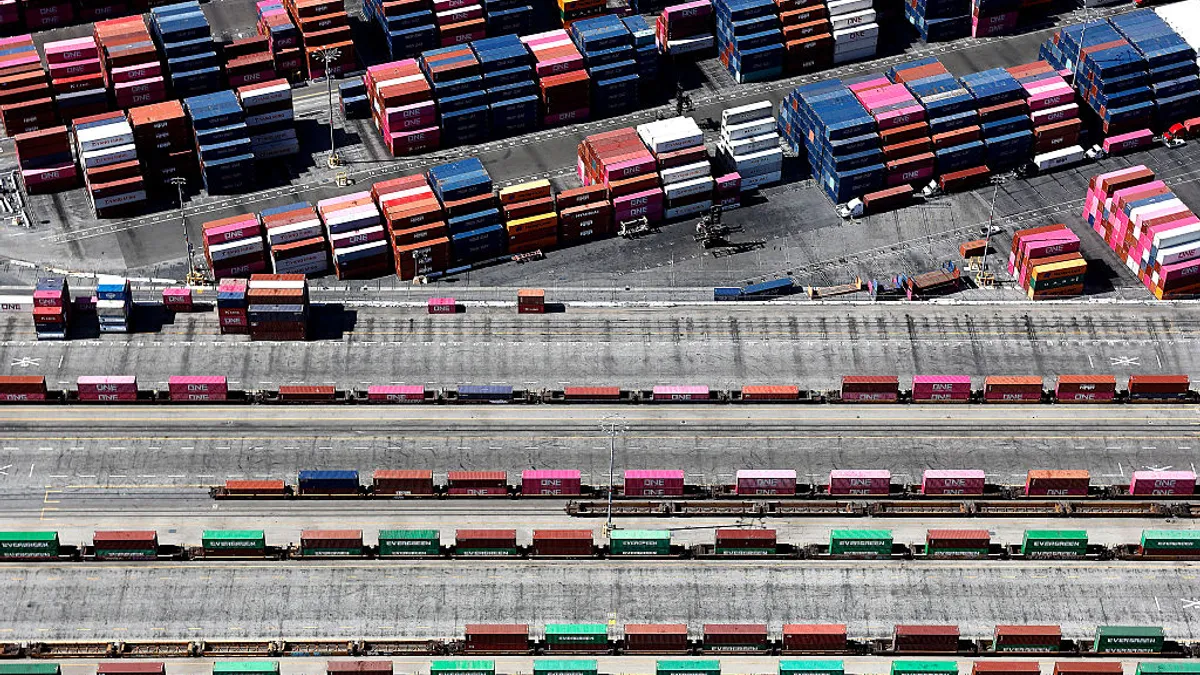

The soybeans traveled from the Ukraine to Turkey to the United States. When they left the Ukraine, they were marked as “regular” soybeans that were fumigated by pesticide. By the time they reached their destination in California, certification documents had been falsified and they were labeled “USDA Organic.”

Twenty-one million pounds of the soybeans intended as feed for livestock were distributed before USDA, prodded by the Post investigation, halted distribution.

We have had to build organic expertise within our business for all verticals.

Michael Castagnetto

Vice President of Global Sourcing at Robinson Fresh

Dairy, beef, pork or other products that came from livestock that ate the contaminated feed could no longer be sold as organic and would damage the reputation of the providers, who had no knowledge of the false labeling.

Thus, as more consumers demand organic food and more distributors handle organic material, supply chain visibility and tracking is more important than ever.

Organic popularity is surging

In the United States, organic food sales increased by 8.4% in 2016, reaching $43 billion, according to a May 2017 report by the Organic Trade Association (OTA). Sales of non-food organic products increased 8.8% to $3.9 billion.

This seems to indicate that consumers are adding organic products to their more conventional purchases.

“The organic industry continues to be a real bright spot in the food and [agriculture] economy both at the farm-gate and check-out counter,” said OTA’s CEO and Executive Director Laura Batcha, at its annual policy conference, “Organic. Big Results from Small Seeds.”

“Organic farmers are not just staying in business, they’re expanding,” Batcha said. “Organic handling, manufacturing and processing facilities are being opened, enlarged and retooled. Organic farms, suppliers, and handlers are creating jobs across the country, and the organic sector is growing and creating the kinds of healthy, environmentally friendly products that consumers are increasingly demanding.”

Organic fruits and vegetables are the largest category, accounting for almost 40% of all organic food sales, rising 8.4% to $15.6 billion in 2016. Almost 15% of the produce Americans ate in 2016 was organic.

And it’s not just produce.

The organic industry continues to be a real bright spot in the food and [agriculture] economy both at the farm-gate and check-out counter.

Laura Batcha

CEO of OTA

Sales of organic meat and poultry shot up by more than 17% in 2016 to $991 million, for the category’s biggest-ever yearly gain. Continued strong growth in that category should push sales across the $1 billion mark for the first time in 2017.

Growing awareness of organic’s more encompassing benefits over natural, grass-fed or hormone-free meats and poultry is also spurring consumer interest in organic meat and poultry aisles.

High costs and certification pose risks to distributors

Farmers face increased risk when they decide to grow organically. There are increased risks from pests, for example, as well as cost—getting certified can cost at least $750—and time—as much as three years—to convert to organic farming.

For example, land used for organic farming in the United States must be free of prohibited substances, including many pesticides, for 36 months before produce grown there can be sold as organic, according to SpendEdge, a global procurement intelligence advisory firm.

In the U.S., farmers must be certified and adhere to Food & Drug Administration (FDA) regulations covering transportation and storage of organic foods from farm to consumer.

Organic farmers are not just staying in business, they’re expanding.

Laura Batch

CEO at OTA

Durst Organic Growers is a Northern California family farm that has been around since the 1800s. The current (fourth) generation decided to go organic and in 1988 planted its first organic crop of tomatoes. A year later, the farm was growing its first organic, fresh -market tomatoes and mixed melons, which they sold in Bay Area markets.

“Durst Organic Growers inspects supplies upon receiving, during production and shipping,” a Durst Organic Growers spokesperson said. “We inspect any foreign materials such as metal, plastics, wood or anything that would be a risk to the raw materials, packaging and finished goods. Our products teams are constantly monitoring the condition of supplies. If we felt there were any safety compromises regarding the supplies, they would be placed in appropriate recycling areas or destroyed.”

The supply chain is vital in making all this work, and it’s not easy. Organic products’ impact on supply chains varies drastically by category, said Robinson Fresh’s Castagnetto. He pointed out that in may cases large farming operations have integrated organic growing into their conventional product mixes.

“However,” he added, “there still remain many categories where organic growing is dominated by small or niche growers that require additional stops for trucks, consolidation of product through freight on board (FOB) or forward distributing service centers, or local purchasing from organic/specialty wholesales.”

Our products teams are constantly monitoring the condition of supplies.

Spokesperson

Durst Organic Growers

Properly refrigerated and monitored trucks — with organics carefully separated from non-organics if the truck is shared — deliver the produce to the warehouse, which must also meet standards.

Most organic foods can’t be stored with other products because of contamination risk. Weber Logistics, a California 3PL, offers some guidelines for organic food warehouses.

- Suitable materials must be used for organic food storage and boxes clearly labelled, noting their contents and origin traceability.

- Records of organic inventory must be kept separately from all other goods in the warehouse.

- Equipment that has been used for non-organic products must not be used for organics due to possible contamination.

- An efficient warehouse management system (WMS) that includes monitoring storage temperatures should provide checks and balances and maintain records of temperature integrity.

As the organic food market continues to grow, 3PLs, warehouses, transportation companies and other supply chain links will need to innovate to keep up, and work with farmers to ensure organic food reaches consumers without sabotaging the organic certification.