This is a contributed op-ed written by Travis Tokar of the Neeley School of Business at Texas Christian University, and Andrew Balthrop and Ron Gordon, both of the University of Arkansas. Opinions are the authors’ own.

Consumer food prices in grocery stores and restaurants have risen 15% since the pandemic began. That fact will come as no surprise to readers.

Policymakers have repeatedly blamed these price increases on multiple factors. Some, such as COVID-19 related issues and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, are undoubtedly contributing factors. However, other common recipients of finger-pointing are dubious at best, such as food manufacturers allegedly engaging in price gouging.

We wanted to know what people in the industry thought about blaming supply chain for inflation. Here is what Ben Ponder — a food manufacturer in Austin, Texas, and a long-time friend of one of the authors — had to say. As it turns out, many manufacturers are absorbing extraordinary amounts of costs even despite raising prices.

“Raising prices is hard; it’s ugly”

Ponder started Ponder Foods in 2019. The “vertically integrated, clean-label food company” makes “minimally processed soups, sauces, dips, and dressings” that are sold nationally through retailers under its various brands. The roughly 100-employee company also manufactures products for external brands.

As a result of higher costs, Ponder has had little choice but to pass some on to his customers, but he believes food prices would be much higher if manufacturers did not fear customer backlash.

“You can’t raise prices as fast as costs are being raised. Raising prices is hard; it’s ugly. It results in tremendous backlash that is uncomfortable and unpleasant to deal with. It risks driving people away.”

Small and mid-sized food manufacturers often do not benefit from the economies of scale, bargaining power, and cost-cutting expertise of their large counterparts, making raising prices all the more critical for managing margins.

Rather than the source of inflation, in many cases the supply chain has been an inflation absorber, sparing consumers ...

Ben Ponder

Founder of Ponder Foods

“When costs get high enough, you lose money even when you’re busy. It’s one thing to fail for not being busy, but it’s awful to fail for being busy,” Ponder said.

Ponder says the price increases that he experiences in his business “fundamentally come down to labor.” As COVID-19 lockdowns persist in other countries around the world, suppliers lack the workforce necessary to produce at full capacity, extending shortages and lead times while driving up market prices.

Finding and retaining factory workers before the pandemic was already a challenging task, but since the onset of COVID-19, it has become even more difficult. The resulting tightness in labor market has forced companies to pay higher wages to find the workers they need.

“In early 2020, you might have paid $12/hr for an employee,” Ponder said. “In 2021 it was more like $25/hr.”

Ponder is clear that he is “all-for” people making a living wage, however he notes that few people seem to understand or appreciate that higher wages can potentially drive higher prices.

Putting it in context

While inflation has dominated public discourse for the past several months, businesses such as Ponder’s have grappled with soaring production costs since spring 2020 after the COVID-19 pandemic began. Lockdown orders caused a surge in at-home dining, a potential boon for food manufacturers. However, as demand for glass and plastic containers skyrocketed — and 8 week order fulfillment times stretched to 53 weeks — container suppliers began implementing various surcharges.

“A $.33 glass jar still cost $.33, but it had $.66 worth of surcharges tacked on when purchased. And the problem was that this started happening everywhere. Every product, from every location or source,” Ponder said.

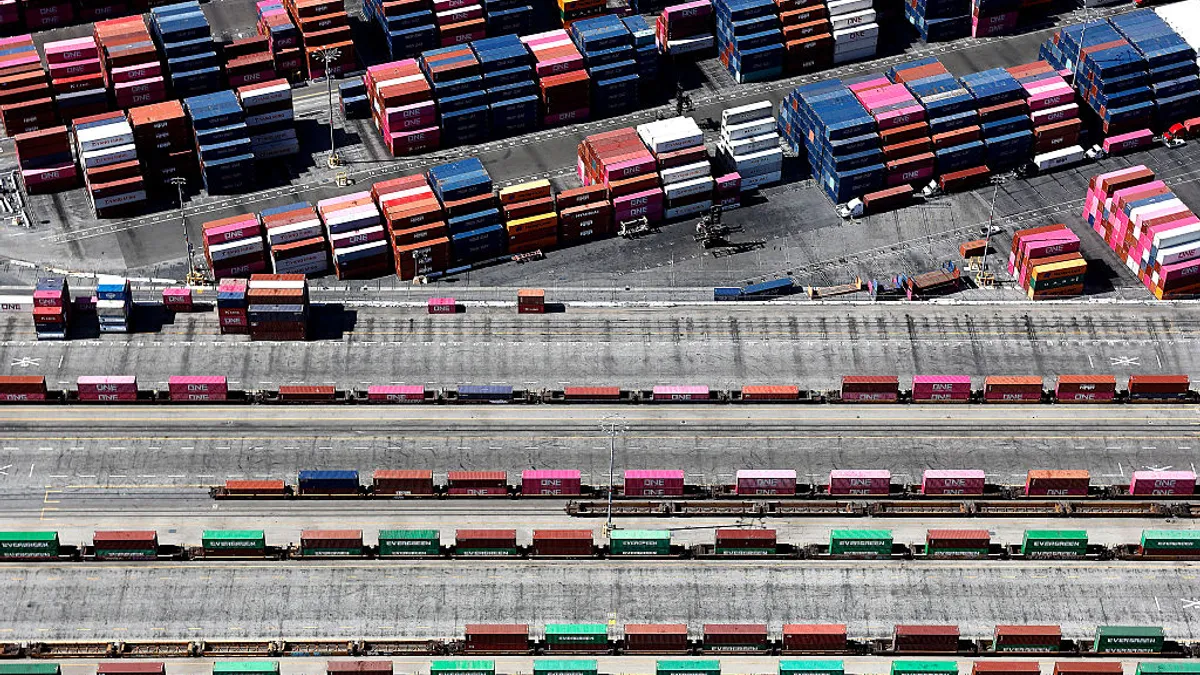

Smaller food manufacturers lacked the leverage to drive hard bargains as suppliers levied new surcharges in response to their own increasing costs and short supply. Ponder Food’s size also worked against it when trying to book ocean transportation.

As high demand and port congestion elevated shipping prices to historic levels in 2021, ocean carriers similarly began to add fees. Large firms avoided (and exacerbated) this problem by purchasing entire ships’ capacity, but a broker told Ponder he would need to pay $22,000 to have a chance of getting his purchased materials onto a container vessel. The fee would not guarantee that his supplies would make it onto the ship — only that they might.

Beyond labor and surcharges, Ponder cites truck transportation rates and global conflict as the primary drivers of higher consumer prices.

Bulwark or scapegoat?

The economic reverberations of the pandemic are still being felt. Particularly in supply chains forced to adjust to turbulent global conditions and dramatic shifts in consumer demand. Rather than the source of inflation, in many cases the supply chain has been an inflation absorber, sparing consumers the brunt of the inflationary pain.

It is amazing, for example, that consumer food prices have “only” risen 15%. Prices food manufacturers pay for the farm-raised ingredients that go into their products have risen 68.2% since March 2020. Given that food manufacturers are also paying more for several things including labor and transportation, the gulf between agricultural commodity price increases and consumer food price increases suggests that many firms are eating inflationary costs instead of passing them on to customers.

Or at least they are eating as many of the costs as they can.

Food manufacturers risk losing customers when they raise prices — but they also have to pay the factory rent, keep the lights on, and compensate their employees. It is a delicate balancing act full of unpleasant tradeoffs, and one with which food manufacturers like Ponder have become all too familiar.