Editor's Note: This article is part of a series on the supply chain effects of changes to the ocean freight industry. All stories in this series can be found here.

Few would be surprised if a shipper left bewildered after an American Association of Port Authorities conference. Talk of five-year plans, infrastructure needs and new technology make for fascinating sessions, but one line stands out as the trade show’s most common refrain: “If you’ve seen one port, you’ve seen one port.”

Ports may have existed since the beginning of global commerce, but today’s institutions are so complex, even their challenges appear unique. Yet, despite the refrain, ports in cities like Charleston and Long Beach have more than just beautiful shores in common.

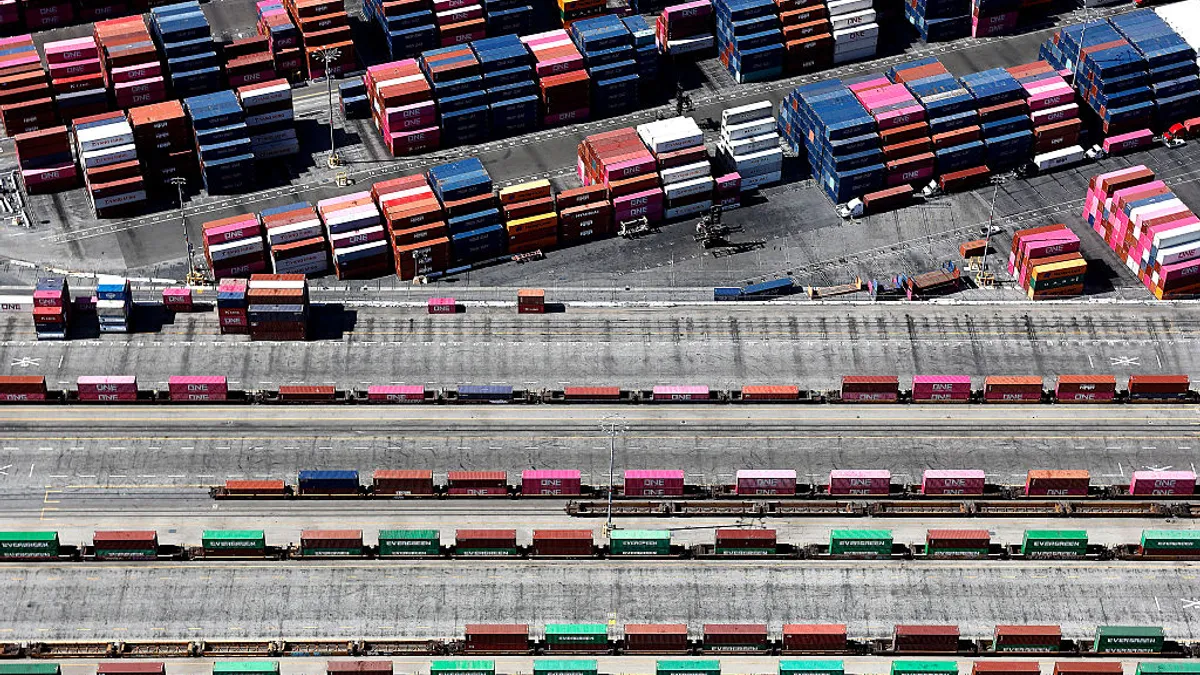

They are a pivotal link in the supply chain, facilitating the movement of goods across modes of transportation. In a way, ports are the middle-man of trade; and, as such, the institutions are often the first link to feel the effects of market shifts.

Given the rapid pace of change in the shipping industry, Supply Chain Dive spoke with executives at the South Carolina Ports Authority and Port of Long Beach to discuss how the latest wave of consolidation may affect the larger chain, and how they seek to minimize these disruptions.

Why ports matter

“The port is an integral part of the whole supply chain because it is really the interface between inland transportation and ocean transportation,” Jim Newsome, President and CEO of the South Carolina Ports Authority told Supply Chain Dive.

“The ability to make that transfer in the way that cargo owners are looking for, and our ocean carrier customers are looking for, is important,” said Don Snyder, director of business development at the Port of Long Beach, in a separate conversation. “There’s three things they’re looking for: They’re looking for speed, reliability and [that it’s] done in a cost-effective manner.”

The best port is the one no-one talks about.

Jim Newsome

President and CEO, South Carolina Ports Authority

In that way, ports are like fulfillment centers, except with cranes and chassis instead of pallets and forklifts. Improving turn-times, dwell-time and individual-unit visibility are key. But according to both executives, one goal is always top of mind: pristine customer service.

“If the shipper or shipping line has to worry about whether we get their truck in or out efficiently, then I don’t think we’re doing our job really well,” said Newsome. He added that the best port is the one no-one talks about, just as few customers comment on the timeliness of an airplane flight, but always complain of delays.

How ports are improving efficiency

However, ports still have a long way to go as stories abound of truck congestion, handling slowdowns and other micro-disruptions at ports that affect supply chains.

“I spent time with a toy company, and actually certain parts of the toy industry are very perishable. You know, they’re like in fashion,” Snyder said. “So we like a lot of cargo owners had an end-to-end system where you could track every toy – which was in what carton, and where it was in the world.”

But transferring cargo between supply chain parties at ports and rail terminals are prone to problems due to a high volume of transactions among unrelated parties, according to Snyder. “Within each of those transactions, it's either successful or something happened: The trucker, the particular shipment, the cargo didn’t get paid and so it’s being held.”

Shippers often refer to this gap of information within ports, or a lack of agency to act upon it, as cargo moving through a “black box.”

Although ports are rarely responsible for the micro-disruptions described by Snyder, a series of them can lead to chronic problems, such as terminal or truck congestion. As a result, ports must often engage their various stakeholders to help bring supply chain partners together and find solutions.

Addressing this concern at the American Association of Port Authorities conference, Nyariana Maiko, CIO and director of information management for the Port of Long Beach identified four KPIs to track as indicators of port efficiency: reliability, visibility, predictability and data integrity.

SCPA’s Newsome adds shippers should also consider a ports’ ability to tailor their services to specific industry needs, the ports relationship with the state, and the ports’ long-term plans.

Ports must consistently adapt to changes in the shipping industry

In fact, a port’s plans for future growth may be most important, as the root of supply chain disruptions may sometimes lie elsewhere — such as in carriers ordering larger ships, consolidating or shifting alliance structures.

The recent arrival of big ships to the U.S. East Coast is a case in point. The prospect raised concerns port turn-times may slow as terminals handled thousands more containers at once, adding congestion to the process.

Yet, Newsome believes SCPA is a success story on this front. “Actually, I think they in a way make us more efficient,” he said. “I would frankly rather have one 14,000 TEU ship than three 4,500 TEU ships. They carry the same amount of cargo,” but use up less berth capacity.

Ports are like fulfillment centers, except with cranes and chassis instead of pallets and forklifts.

Supply Chain Dive

Newsome has been at the SCPA since 2009, and from that moment began preparing to receive 13 or 14 thousand TEU ships at the Port of Charleston. “If a shipping line orders a big ship it takes them 3 to 4 years to get delivery,” according to Newsome. “Nothing happens in the port industry in a short period of time.”

In this sense, ports face a dual challenge of ensuring the promised level of service today and worrying about their competitiveness 20 to 30 years from now. “Lines are not going to wait for tidal restrictions to get in and out of ports,” he said. “So does the port have the wherewithal to deepen their harbors, to build new infrastructure on a timely basis?”

“We’ve been working at this for 8 years, basically, and the real signature of all that is the amount of investment we have to make,” Newsome said. The SCPA and South Carolina are together investing $2 billion in the next five years to help support increased cargo volumes from the trend toward larger ships. The investments include terminal expansions, and waterway improvements, as well as investments to inland infrastructure.

SCPA is not alone: Ports across the U.S. East Coast are boosting their infrastructure to handle more cargo. “The ports are playing catch up in many respects to the necessity to handle the bigger ships,” according to Newsome. The scale of investment suggests the big ship era is just beginning.