Dave Aquino is not new to supply chain, with his 25-plus year career that included uniform manufacturing and sales. But he was new to personal protective equipment sales when he founded Certain Supply in April 2020 after seeing an opportunity for supply chain to help pull the U.S. out of the COVID-19 crisis.

"I kept hearing about the horror show in supply chain availability," he said, and he decided to use his experience in contract manufacturing and quality compliance standards to bring PPE to the U.S.

But within the first year, the company lost $250,000 from one customer that purchased products over six weeks with a credit card, then pulled the money back.

"There's heavy risk on picking the right supplier, but there's a demand-side challenge too," Aquino said.

The pandemic brought out a lot of bad actors, as an imbalance in PPE supply and demand left openings and vulnerabilities for fraud and counterfeits. Increased need levels, combined with confusion over where to find products, paved the way for these problems. Reliance on foreign supply chains for products also contributed, given the challenge in monitoring supply chains from afar and the number of times items switched hands.

"The pandemic has been a major driver of fraudulent activity," said Amber Moren, area general legal counsel at 3M.

PPE fraud may involve selling counterfeit products or items that don't meet the proper standards. It can also include making misleading or false statements about a product's effectiveness, or using these statements to sell or contract for a sale.

Supply-demand mismatch opens the door to fraud

Homeland Security Investigations started Operation Stolen Promise in April 2020 to crack down on pandemic fraud and other criminal activities.

In January, federal officials charged a man in Philadelphia with pocketing a $712,500 medical gown deposit and using the money for online gaming and other personal charges. Federal officials said in February they seized about 11 million counterfeit 3M N95 respirators over the span of a few weeks.

Operation Stolen Promise, by the numbers

- 2,234 COVID-19-related seizures (prohibited pharmaceuticals and counterfeit masks, for example)

- 316 criminal arrests

- $54.3M illicit proceeds seized

- $37.9M Cares Act fraud seizures

Source: U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement

Legitimate supply increased over the course of the pandemic, so it's now closer to meeting demand. 3M started ramping up N95 production in January 2020, before most in the U.S. were aware of the looming health crisis. This was the same time that fraudulent activities started ramping up as well, Moren said.

3M opened an anti-fraud hotline in March 2020, which fielded more than 14,400 calls globally. Distributors were misrepresenting their relationship with 3M or their access to the respirators, Moren said.

"They were offering huge quantities that were out of line with 3M's production, saying in a few cases they had trillions, when they had access to no respirators at all," she said.

The company is running the hotline in multiple call centers, using agents speaking different languages, as the problem has been global.

Even though 3M now produces more than four times the number it produced a year ago, cranking out 95 million N95 respirators a month, Moren said there's still a supply and demand imbalance.

And the more recent shift is toward counterfeiting. "By and large, the earlier activity has been replaced by a significant and still increasing volume of counterfeit 3M PPE, and N95 respirators in particular," Moren said.

Manufacturers and distributors vet and get vetted

The difficulty securing PPE not only led to bad actors entering the marketplace, it led to legitimate and well-intentioned start-up companies and nonprofit organizations forming after sensing an opportunity and need for PPE.

Nonprofit Project N95 was founded in March 2020 to help secure PPE and, subsequently, testing kits for essential workers and vulnerable communities.

One of the first actions, said Anne Miller, Project N95's volunteer executive director, was creating a vetting playbook, as it recognized the lack of trust in the marketplace among procurement leaders buying PPE. Project N95 translated the federal regulations into guidelines to check each product against, she said.

Each organization has its own method for vetting vendors. Here are a few ways they do it.

Project N95

Miller said Project N95 watches for any mention of the Food and Drug Administration when procuring N95 masks. A box or product with an FDA logo is likely not legitimate.

"You can't have a product bearing the FDA logo. That is not allowed," Miller said.

A company can register with the FDA, but it's not an indication that the FDA cleared the products.

"Whenever they say FDA-approved, that sets off an alarm bell. They do not approve in this category. They approve drugs and clear products," Miller said.

Project N95 also checks references, verifying whether the supplier or individual has sanctions against them, bankruptcy proceedings, a reputation for fraud or other notable findings. It also exchanges vendor lists with the American Hospital Association.

Miller said Project N95 only works with authorized distributors or the manufacturers, avoiding gray market products. It prefers to buy directly from the manufacturer if possible. It's hardest to do this with glove manufacturers.

"They're in such high demand, and the minimum order quantity at the factory is so high you need to go to a distributor," Miller said.

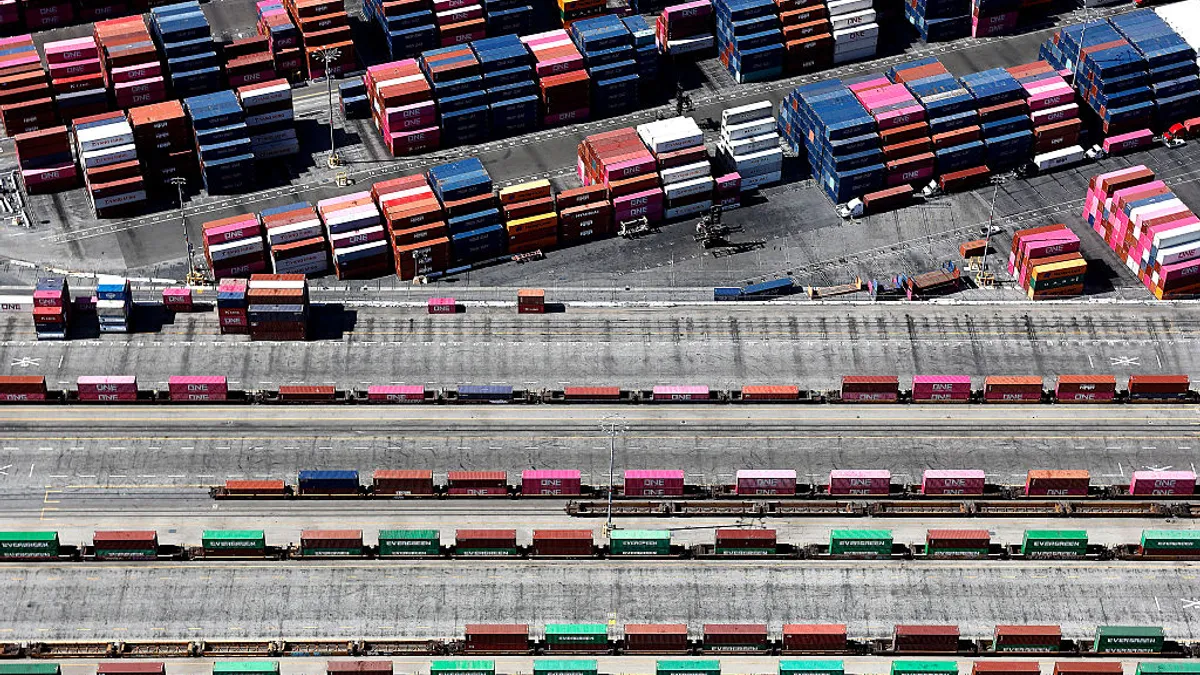

Middlemen buy large lots and break those down to sell to multiple distributors, who then may resell them again, each time at a mark-up and with additional paperwork.

"There's a lot of markup. By the time you buy landed gloves in the U.S., it's very hard to know that those gloves are from a legitimate source," she said.

Ideally, Miller wants to see the products go from the manufacturer by company truck to a bonded warehouse, monitoring the chain of custody.

With increased production, it has become easier to source N95 respirators, especially in the U.S., and Project N95 now sources most of its orders direct from U.S. factories. Then there's only one level of paperwork, making it more traceable.

Apple Trading Company

Bryan O'Halloran co-founded Apple Trading Co. in 2020 to sell nitrile gloves. In addition to asking manufacturers for their FDA registration letter, it also asks the FDA for the letter.

"If we don't get the same one, we won't move forward," O'Halloran said.

Apple Trading Co. also verifies the company's SGS documentation, which comes from an international inspection agency that verifies authenticity and compliance, reducing risk.

"We caught someone a few weeks ago with an invalid SGS," he said, adding that he did not move forward with that company either.

"By the time you buy landed gloves in the U.S., it's very hard to know that those gloves are from a legitimate source."

Anne Miller

Project N95's volunteer executive director

Apple Trading Co. tries to work directly with manufacturers, but sometimes works with brokers local to the manufacturing site. While it runs background checks on potential business associates, that's harder if the associates are in another country. If O'Halloran can find them on LinkedIn and they use the same profile photo there as on WhatsApp and other sites, that's a good sign.

"Someone could create that profile and pretend to be that person. But there are histories on LinkedIn. It all adds to the evidence that they're real," O'Halloran said.

Apple Trading Co. also asks for references from U.S. customers.

"If the items are only on Alibaba, that doesn't add up for us," said O'Halloran. Companies selling large volumes would typically sell via multiple channels. Distributors have also offered high volumes of stock that don't seem reasonable.

"They're just looking for bank information," he said. "They want us to send proof of funds. That's not how we work."

Certain Supply

Like Apple Trading Co., Certain Supply started up during the pandemic, providing a range of PPE and sanitizing products to the B2B market. Aquino sees a lot of customers after other companies made false promises and took their money.

"The big takeaway is you have to prove you're bonafide each day," said Aquino. "We have to prove ourselves on the product side and on the demand side."

He leans on his background and contacts in uniform production to contract with factories, understanding which ones have the necessary certifications and verified materials.

"We have our own folks on the ground in key countries to monitor, and that's enormously helpful," he said. Trust but verify when working with known parties, he said.

Even after getting burned with the $250,000 loss, Aquino said Certain Supply does not demand payment up front.

"We desperately need [the payment] but it's not a good practice," Aquino said. It requires up-front payment for contract manufacturing but otherwise expects full payment at the time of delivery and invoicing.

Verification through videos and tech

If the distributor or manufacturer says they have stock, the buyer needs to verify it. O'Halloran said after asking for verification, the seller will often stop replying. One way to prove possession is getting a video of the gloves in the box, packaged with the supplier's name and showing documentation like a bill of lading, said O'Halloran. O'Halloran may also ask the supplier to put the buyer's name on a piece of paper with the date, to ensure it's current.

On the flip side, O'Halloran has to prove legitimacy to his customers as well. He'll give a warehouse tour, opening a box of gloves and showing them on a Zoom call. He sends product samples and registers the company in places like Thomas.

"[The customers] have to get so comfortable they pull the trigger," he said. The trust building comes from working with someone more than once.

"There's no area of the world untouched by counterfeit activity."

Amber Moren

Area general legal counsel at 3M

Technology can help identify legitimate PPE products, in some cases. Powecom includes a coating on its KN95, much like the scratch-off coating on a lottery ticket. The serial number can then be entered onto the Powecom site to verify legitimacy.

Moren said 3M has embedded technologies in its respirators that help identify counterfeit products based on packaging information and other criteria.

"For the most part, we don't share what we would refer to as ‘counterfeit tells,'" she said. "Once a counterfeiter learns what they are, they can correct for it."

3M gets hotline inquiries from healthcare providers, law enforcement and individual consumers asking if their product is real, if the distributor is authorized and about the prices distributors are charging. 3M's price on N95 respirators has not changed during the pandemic.

3M battles respirator fraud

"We messaged that early, and it remains true," she said. 3M published pricing on its website for reference. "We continue to see inflated prices charged by different companies that have no relationship with 3M," she said, adding that 3M takes action against any authorized distributors charging above the list price.

3M's trademark and brand protection team works closely with U.S. Customs, and the company has provided the agency with training to spot counterfeit products. The majority of counterfeit N95 respirators have come into the U.S. from manufacturers overseas, and the counterfeit respirators are found around the globe, Moren said.

"There's no area of the world untouched by counterfeit activity," she said.