NRF RETAIL CONVERGE — After a year of temporary closures, rapid and extreme shifts in product demand, and tidal shifts to more digital and omnichannel shopping, retailers had to decide, learn and execute more quickly than ever before. All of that put stress on retailers' supply chains and the personnel making them function.

The response to a fast-changing world and unpredictable future is captured in an all-encompassing byword: agility. It's a hard word to avoid when describing how retailers navigate and survive the unending torrent of challenges the past year and a half has brought. In many cases, those were challenges that already existed for operators but were exacerbated and accelerated by the pandemic.

"Agility," along with other bywords like "resilience," is tough to define, partly because it's a catchall for a set of practices, and also because retailers find different ways of becoming agile. In many cases, it may simply mean pivoting as quickly as possible to respond to a sudden change in demand.

But speed alone can't guarantee survival. Tony Zuazo, Dollar General's executive vice president of global supply chain, noted at the National Retail Federation's "Retail Converge" conference that a company can be fast in its supply chain but not necessarily successful. "We like to balance the speed with a cost lens and also a quality lens," Zuazo said at a panel on supply chain disruptions.

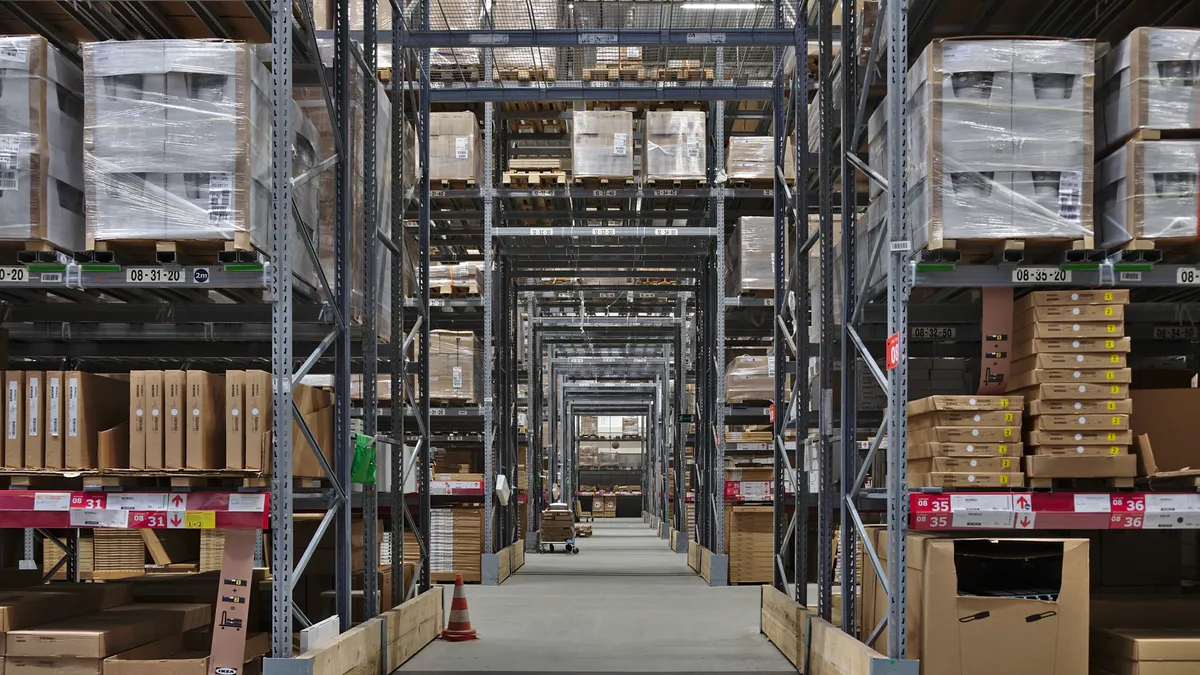

To help the discounter keep product moving quickly, while minimizing costs, Dollar General has a single integrated distribution platform, according to Zuazo. That means a store can be moved from one distribution center to any other in the network and receive goods by the next day, which is key to minimizing disruptions and keeping up with Dollar General's monster footprint growth.

Also on the panel was Colin Yankee, who heads up supply chain for Tractor Supply. Yankee defined agility as the ability to build options into the retailer's supply chain and use those to serve customers.

That means, in turn, assessing product flow options in the sourcing base, lead times and the mix between exporting and domestic sourcing, capacity within vendor and logistics third-parties, and constraints within the entire supply chain.

'Massive volumes of returns'

Reverse logistics came to the fore last year as well. More online shopping than ever before meant more returns. The NRF has estimated that consumers returned $428 billion worth of merchandise in 2020, or about 10.6% of all retail sales that year.

Retailers that, amid the temporary closures, pivoted to being digital-first businesses also had to quickly adapt to the volume of returns coming in.

At American Eagle Outfitters, that not only meant a larger volume of returns, but those returns were coming in from different points than in the past.

After the retailer closed its stores in March 2020 and pivoted to online sales, American Eagle's two U.S. distribution centers soon were deluged with multiple weeks' worth of backlogged returns that normally would have entered the supply chain through the company's stores, according to Brandon Friez, vice president of supply chain transformation at American Eagle.

"Our distribution centers weren't really equipped to deal with massive volumes of returns coming," Friez said at another panel during NRF's virtual conference. "So on top of the growing e-commerce business, the growth of returns, we really outgrew the systems that we had in the distribution center."

American Eagle, working with Optoro, which sponsored the NRF session with Friez, worked to speed up the time between a return initiated by the customer and a product moving back into stock for a resale, as well as to understand why customers were making returns in the first place. Friez said the span between an item being returned and restocked went from a multi-week process to a multi-day process.

Today, "returns are coming in, they're being re-commerced immediately," Friez said. "We're doing a level of editing on the returns to kind of filter out items that may be unsellable, and then we have a reprocess prompt to get those items back and sell them as soon as possible. That's been hugely successful for us to help reduce markdowns and raise [Average Unit Retail] on the resale of goods."

With all ballooning returns come multiple cost and environmental consequences. "We have to really figure out how to make [reverse logistics] cost-effective, and as always, it comes with scale," Sarah Clarke, chief supply chain officer of PVH Corp, said in an NRF panel. "The mathematics around profitability are changing dramatically. We're moving to much bigger, broader assumptions when it comes to profitability than we have done in the past."

As Under Armour Chief Operating Officer Colin Browne noted, reducing costs of reverse logistics can be a competitive advantage for the players who can do it. "It's a nonnegotiable," Browne said. "If you want to play in today's world, you've got to figure it out."

Surging demand, lagging supply

With consumers returning to stores and spending at high rates, demand is up. The return to something like normalcy domestically presents its own set of challenges for supply chains, however.

In some areas where goods are made, countries are struggling to secure vaccines and contain the COVID-19 pandemic within their borders, which could slow the production of goods. At the same time, shipping capacity has been limited relative to demand, raising freight prices astronomically in many cases.

"There does seem to be some revenge shopping going on out there," Browne said. "For those of us that are looking to source products from the other side of the world, we all know the problems in transportation and logistics. Just getting containers in time is incredibly difficult. And so I think it's going to put some real pressure on supply chains to deliver against that. We're all trying to get ahead of it."

Clarke's PVH Corp. is a fairly useful case study in how retailers and brands are handling the year.

On the company's most recent earnings call, Chief Operating and Financial Officer Mike Shaffer said the company's estimates for fiscal 2021 don't include any assumptions about new COVID-19-related closures or lockdowns, according to a Seeking Alpha transcript. At the same time, PVH is monitoring "industry-wide supply chain headwinds." The company is building in four- to six-week inventory delays, and additional air freight and other costs into its financial outlook for the year.

Looking ahead, Clarke said at the panel, "I think we're still going to be living through higher prices and shifting consumer behavior — and the change in agility is going to be the name of the game."