It could be a bounced e-mail, a telephone that rings into oblivion, or a registered letter from a law firm — all buyers have felt the cold sweat and the heart palpitations of a supplier discontinuing a critical part, or worse, closing their doors. Every product or process, and even suppliers, have a lifecycle that supply chain managers need to understand and recon with.

Supply chain managers need to craft sourcing and supply management strategies in all phases of their product’s lifecycle, from introduction to end of life. Active participation in lifecycle management planning and decision-making provides a window into the marketing, operational and financial performance of their company. Properly aligned supplier selection and management also helps to address and manage risk across the supply chain.

The 4 stages of a product's lifecycle

The product lifecycle can vary in length, from months to years. In a typical industrial product, for example a metering valve, a variable speed motor, or a vacuum pump, two to three years may be a customary time frame. But that timing may be considerably cut with a technology driven or seasonal consumer product , such as a computer monitor, an e-reader, or a snow blower.

There are four customary stages in a product’s life cycle: the introductory phase, the growth phase, the maturity phase and the decline phase. Each phase is markedly different and often requires different value chains. Supply managers need to craft supply strategies that reflect the unique needs of each phase.

The introductory phase is when a new product is launched into the market.

In this phase companies are trying to gain initial market share, often as a result of a gap in the market or a failure of a competitive product. Time to market is essential in this phase and suppliers need to be able to respond quickly to accelerating market demands, uneven schedules, and quick changes in design or operating characteristics. These suppliers embrace their roles. They work well with rapid engineering changes, prototype manufacturing, and even back of napkin drawings. They also act in the role of surrogate partner, offering unique skills and experience to the buyers and engineers they work with.

Cost is often secondary to responsiveness, with the assumption that the cost curve will improve during the next phase of the product life cycle. Suppliers who are responsive and specialize in small production lots and prototypes are the best in this phase.

An example of a product in an introductory phase would be a newly designed portable blood analyzer used in the medical industry.

The growth phase is often considered the most important one.

Production accelerates throughout this phase and related costs in labor and material flatten as manufacturing quantities increase. If the product is successful and market demand is high, there is continued pressure on the procurement organization to drive the supplier to meet production goals and aggressive cost targets.

Suppliers with a focus on operational excellence are often chosen to wring out costs and ride the introduction phase for as long as it lasts. Suppliers who can scale and manage downstream capacity bottlenecks are important in this phase.

In this phase, the portable blood analyzer has been released to market and has great acceptance. Demand is high and manufacturing is ramping up.

As the growth phase slows, products enter the maturity phase.

Production slows to reflect reduced customer demand, and the quantities of parts purchased from suppliers are lower as well, creating quantity driven upward price pressure. Materials may also be harder to get, as suppliers work through their own product lifecycle challenges, and those of lower their tier suppliers.

The suppliers chosen for the growth phase are often the same for the maturity phase, but they may not enjoy the operating margins they once enjoyed. Strong supplier relationships are important in this phase to maintain supplier interest in changing business conditions and also to provide high service levels for products already in the field.

Demand for our portable blood analyzer is beginning to wane as the market is becoming saturated, the technology is lagging, a competitor has introduced a better or more cost effective alternative, or the ‘new and improved” version has been launched to capture additional market share.

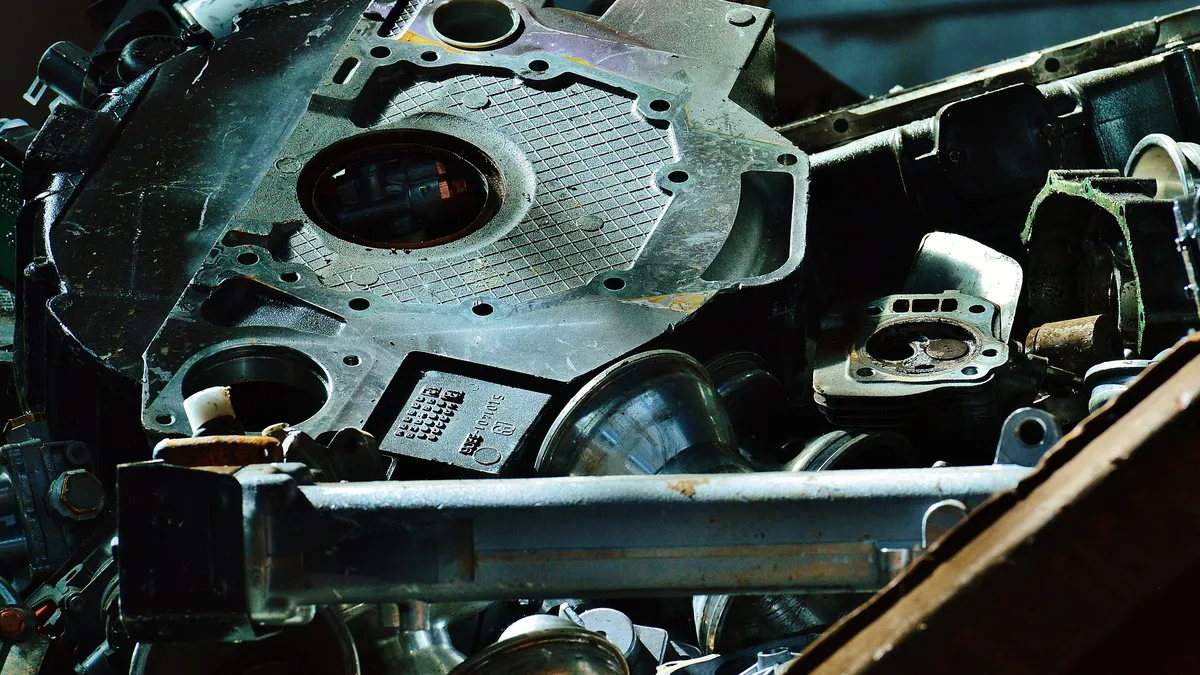

Before end of life, products see the decline phase.

Production quantities continue to fall, as are related material purchases. There are supplier challenges as well. Cost of purchase content increases, as the quantities purchased are low and often poorly forecasted, resulting in special orders and extended lead times.

Sadly, our once leading edge portable blood monitor is collecting dust in hospital supply cabinets. But, there are still units in the field that continue to operate but might need repair or refurbishment. Customers need to be supported and that support for older products might enter into the purchasing decision for new ones coming to market.

During long product life cycles, suppliers may change or no longer be making the products that they once did, forcing buyers to create expensive special product runs with the prototype suppliers of yesteryear or finding new niche suppliers. Solving production and field service problems for products in the decline phase are challenging, but critical to customer service. Suppliers play a key role.

How to manage end of life

All products reach an end of life stage. Your company’s products are discontinued at some point and products that you purchase from suppliers are ultimately discontinued as well. In some cases they are replaced by the latest and greatest new and improved version as a result of product lifecycle management. But in some cases, buyers may hear the bad news that the products they buy are now obsolete and impossible to buy.

Some suppliers handle end of life proactively. Large companies with multiple products may publish an end of life listing, advising customers to place final orders or purchase the last available inventory. Other suppliers may notify their customers that they are planning to discontinue items, allowing the buyer a chance at a last time purchase. Still others find no obligation to notify their current and past customers and buyers are surprised to learn of a product’s demise, typically when they really need it.

Suppliers also close their doors, sometimes abruptly. Bankruptcies, succession challenges, health issues, market conditions, natural disasters, and even boredom result in suppliers going out of business. In strong supplier relationships, this should not come as a surprise, and there should be enough notice to allow the buyer to make alternative arrangements to ensure continuity of supply. But in some cases, these businesses shutter almost overnight, forcing the buyer to scramble.

The news is not all bad for supply chain managers. End of life situations also offer an opportunity to find new suppliers, incorporate changes in technology, lower costs, and reduce risk. More than one supply manager has been relieved to learn that a recalcitrant and poor performing sole source supplier is ending production, forcing colleagues in engineer and design to address the issue by finding an alternative product.

Today’s focus on supply chain integration makes it critical to create active supply chain strategies around product lifecycles in your own company. In addition, understanding the product lifecycle plans from key suppliers offers insights into supply planning and pricing trends, while addressing and reducing risk. Product lifecycles are in constant motion. Finding the right suppliers who understand their role is critical.