Editor’s note: This article is part of a series on sustainability. You can find the whole package at our landing page.

For retail, the most daunting task in decarbonizing — the most complex in terms of data and execution — is also the most critical.

Scope 3 encompasses emissions up and down the value chain, from materials to the supply chain and so on to the consumer’s final use of a product. It is, by far, the largest share of retail’s footprint. Indirect scope 3 emissions account for 90%, and sometimes up to 98%, of retailers’ greenhouse gas emissions, according to the National Retail Federation.

And because of their vast scope 3 footprints, retailers are responsible for roughly 25% of global emissions, according to a report from Boston Consulting Group and Ascential’s World Retail Congress.

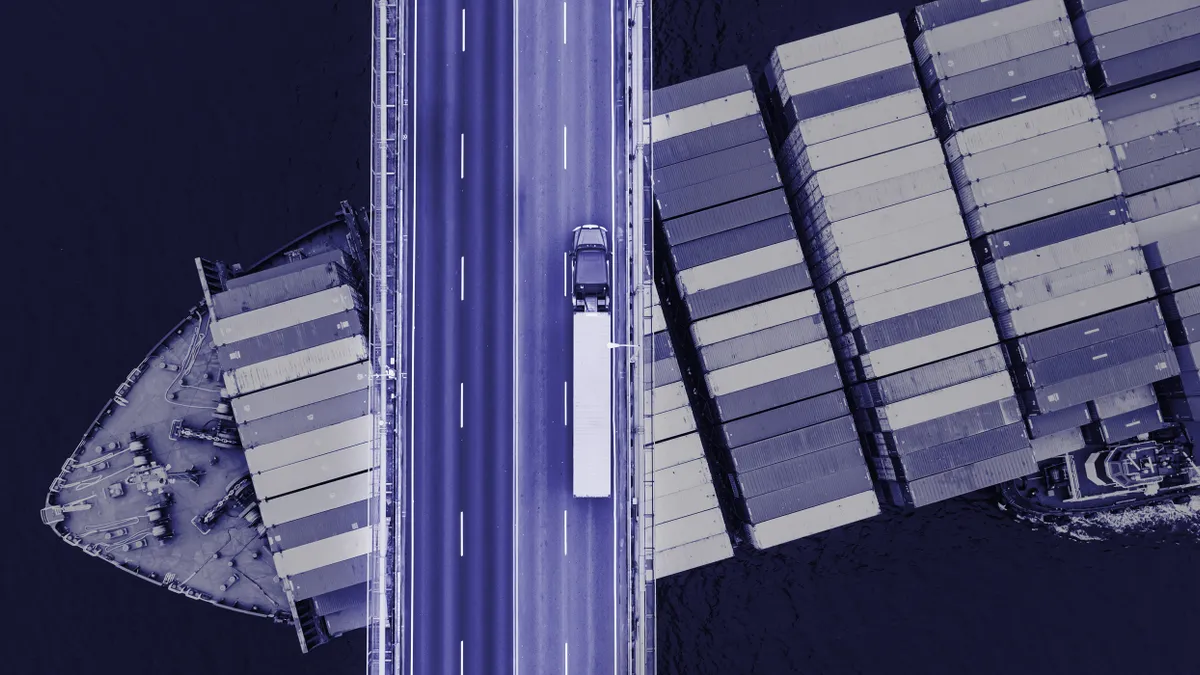

Because the emissions are indirect, they also are the most difficult to track and change. Consider the difficulties retailers have had over the past 12 months just pulling the reins on their supply chains to get products profitably in the country to sell.

And as with last year’s struggles, the very nature of supply chains help explain the difficulties in scope 3. Instead of owning factories and directly controlling all or even much of their own production, brands outsource production to a geographically and economically complex network of suppliers who have their own interests and operations to worry about as well. Even getting data and understanding the emissions footprint of supply chains is a difficult task.

But that’s not a reason not to take action. Retailers can get started with what they know, and what they can change today, experts say. Imperfect data and initiatives are better than none. The stakes are way too high, and the industry much too far behind, to be timid about scope 3.

“The reality of where we are as a society is that we need to put the wheels on the car as it’s racing around the tracks,” Shalini Unnikrishnan, managing director and partner at BCG, who leads sustainability for the consulting firm’s consumer and retail practice, said in an interview. “Is there a huge data problem? Absolutely. But there are smart ways for companies to get moving and have impact in the absence of perfect data.”

‘Significantly behind’

There is a huge gap to close on scope 3 emissions, and very little time to do so at this point. And yet, many in the industry still haven’t started.

A BCG study shows just how much work is yet to be done in the industry. Of retailers surveyed, just 18% are on track to meet their scope 3 targets. Another 18% are activating plans but are behind schedule.

Nearly a quarter (24%) of retailers have scope 3 targets set but no plans for how to actually achieve them, and 6% have no plans at all. Another 35% have plans but aren’t making progress against their scope 3 targets or are unsure of their progress.

In other words, for roughly two-thirds of surveyed retailers the most that can be said of them is that they are making zero progress on scope 3.

All of that said, some retailers are starting to set targets and take action on scope 3. According to a Fitch Ratings analysis, the number of retail companies that have set science-based emissions targets has more than doubled since 2019, and those that have committed to targets has grown from nearly nothing in that time to 36.

Target and Walmart — among the largest retailers in the U.S. and often agenda setters for the industry on both operational and social issues — have each made commitments on supply chain emissions and scope 3.

“We have to do something. It’s getting worse.”

Ting Chi

Professor and Department Chair of Washington State University's department of apparel, merchandising, design and textiles

But the progress to date is not nearly enough to bring the industry in line with goals set by the Paris Agreement.

“When you look at net zero targets, we’re significantly behind, and I think we will fall further behind,” Simon Geale, executive vice president at Proxima, said in an interview. “That will either be the catalyst for change, or worse. I expect there to be huge amounts of more progress over the next decade. But it’s such an important decade, there’s a risk that [with] all our progress, ... we’re still falling behind.”

Take the fashion industry as a very important example given its footprint. The sector was responsible for some 4% of greenhouse gas emissions in 2018. As of 2020, fashion is on pace to generate more than double the 2030 emissions target set by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, according to McKinsey.

“I don’t know that we can achieve the goal by that time, but it shouldn’t be a reason for doing less,” Ting Chi, a professor and department chair at Washington State University’s department of apparel, merchandising, design and textiles, said in an interview. “We have to do something. It’s getting worse.”

Digging into the data

Merely measuring the size of a company’s indirect footprint is a complex, daunting task, full of sleuthing, data gathering and estimating. Even to do so with precision requires a lot of estimating.

In the BCG survey, one of the most cited challenges in achieving emissions goals was lack of access to relevant data. “The challenges of data don’t give us the luxury of waiting,” Unnikrishnan said.

Those just starting to measure their scope 3 emissions are typically doing the most estimating and guesswork. They might use databases that convert economic inputs and outputs and send data into indirect emissions estimates. “Is that the most robust method? No,” William Theisen, CEO of climate-focused consultancy EcoAct, said in an interview. “But it is a good starting point to understand where are the hotspots within your supply chain on scope 3.”

On the other end are estimates based largely on primary data from suppliers and the specific products sold in retail spaces. Theisen also said there is a “middle ground” between pure estimates and massive primary data collection.

“If you’re a fashion company, you can look at raw materials you’re using in your clothes, and the transportation and distribution — look at different buckets of information,” Theisen said. “We can use that to get a more accurate carbon footprint within scope 3. But of course, supplier data, primary data, is always the gold standard.”

But even primary data is just that: data. Within data, there is a lot of variation in quality. Perfect data is, for now, probably infeasible.

“If I'm a grocer and I'm selling a head of lettuce, perfect data is that I know … exactly where it's grown, how it's grown, how it's harvested — what happens to it every step of the way. Which refrigerator did it fit in, what truck did it move in, how many times did it move?” Unnikrishnan said.

But it doesn’t stop there, for scope 3 tracks all the way to the final use and destination of products. “And then finally, after somebody bought [the lettuce], did they eat it? Did they waste it, and what happened to the waste? That's perfect information,” Unnikrishnan added. “So now you understand, we're not going to get there in a reasonable amount of time.”

“A lot of firms I’m seeing at the moment are paralyzed by how difficult it is to get the data."

Simon Geale

Executive Vice President at Proxima

Estimates based on spend at least give retailers a sort of heat map of where the largest sources of emissions in their supply chain are. To get primary data, retailers can build lists of their largest suppliers, core suppliers and so on, and then essentially ask vendors for the data.

“Starting from the top, they're basically building these questionnaires that are asking suppliers to provide details to what their carbon emissions are,” Tyler Higgins, retail practice lead and managing director at consulting firm AArete, said in an interview.

Data, to be useful to companies and the planet, also has to be correct. “Data has to go hand in hand with validation,” Unnikrishnan said. “It has to go hand in hand with auditability, with traceability. That’s a really critical part, that’s the holy grail.”

In Unnikrishnan’s view, advanced technologies such as blockchain can help make validation and traceability throughout the supply chain possible.

All of this is complicated even more by the tension between the desire to track emissions — perhaps for climate-minded investors or to score sustainability points for customers — and concerns about greenwashing.

Highlighting that tension was a recent controversy around one of the most common tools used by fashion brands and retailers to track their various sustainability footprints. Earlier this summer, Norway’s consumer authority called out some retailers, including H&M, for making sustainability claims using a material index from Higg, created by the Sustainable Apparel Coalition.

Higg also has scope 3 impact estimating tools, though those weren’t at issue in this instance. The Sustainable Apparel Coalition scrambled to review the data and methodology behind the Higg material index, which is used by hundreds of brands. Not long afterward, an investigation from Quartz found H&M wasn’t even citing Higg scores for its products correctly in many instances.

While not directly related to scope 3 tracking, the controversey over the Higg Index and H&M shines a light once again on the difficulties even in the simpler forms of environmental tracking — that is, using indexes to provide estimates on a footprint. But time and again, experts told Retail Dive in interviews that companies need to get started tracking even in the absence of perfect data and perfect tools.

Adventures in decarbonization

Tracking emissions isn’t the same as reducing them; it’s only a step in the process. And it doesn’t even have to be the first step in every instance.

“A lot of firms I’m seeing at the moment are paralyzed by how difficult it is to get the data, and they forget that actually you can go and do stuff,” Geale said. “You [can] go work with a supplier to switch to an electric fleet, or to reduce the number of journeys that are needed or change the specification on packaging, or to make something circular or take water out of the process. Automatically, you are reducing the level of emissions in the bigger picture.”

Geale added, “And that’s more important to do than to necessarily be able to measure.”

As Jess Dankert, vice president for supply chain with the trade group Retail Industry Leaders Association, noted, many major retailers are already having strategic conversations within their supply networks and transportation networks for operational reasons. “We see the sustainability and emissions piece become more of a factor in that,” Dankert said in an interview.

Retailers are also looking at the mix of modes they rely on to move goods, asking questions about the role of intermodal and rail transport in reducing emissions, according to Dankert, who added that there are many “interesting conversations” around emissions taking place and a “rapid pace of evolution.”

Erin Hiatt, vice president for corporate social responsibility at RILA, noted also that many emissions reductions yet to be made can be tied to efficiency, such as reducing empty miles in transportation, freight matching and intermodal transport. “There’s a lot to optimize there while companies keep an eye on low and zero emission-fleet opportunities as that technology and infrastructure develops.”

“If you don’t get U.S., China, India and other large economies tied into this, you don’t achieve it.”

Simon Geale

Executive Vice President at Proxima

When it comes to supply chains, size is a difference-maker. “The level at which you're able to influence your suppliers is really critical in how quickly you can decarbonize your own supply chain,” Geale said. “Take the example of Walmart and Costco. Some time ago, Walmart took a position they were going to be able to influence their suppliers, create some collaborative solutions. Costco took the position that they didn’t have the ability to influence their suppliers.”

There is also the question of who will pay for transforming the emissions profile of supply chains. Many factories operate on thin margins in countries less wealthy than those where retailers and their customers are located. Chi notes that for many garment factories in the developing world, which produce the vast majority of clothing, if carbon reduction adds even modestly to their costs it could wipe out their profit margin.

“To meet one demand or one requirement that would add to the unit cost, they lower the quality for other things,” Chi said. That could end up hurting other sustainability measures. But Chi also notes, “Cost sharing could be a very important incentive.”

Scope 3’s operational and data challenges are as complex as supply chains themselves. But there is one very simple, certain way to reduce emissions: sell fewer SKUs.

“One possible solution we talk about is we can buy less at higher price points,” Chi said. “We talk about more durable goods that you can wear for 10 years instead of two or three years and throw away a $10 T-shirt.”

The role of policy

Despite some recent progress, it’s difficult to see how the full industry gets across the finish line, or even close to it, without government intervention.

“If you don’t get U.S., China, India and other large economies tied into this, you don’t achieve it,” Geale said.

Or, as Chi put it a little more optimistically, “If government can take the leadership, I think it would happen sooner.”

The industry, too, acknowledges this. “There is a role for policy,” RILA’s Hiatt said. “It’s hard to say what that it is. You kind of have to react to what you see proposed.”

As Chi pointed out, government involvement can take the form of regulation and mandates, as well as financial incentives and investments in the infrastructure needed for emissions reductions on a mass scale.

Hiatt pointed to renewables, which currently lack the capacity to meet the demand as projected under current global climate goals.

“These companies are setting goals based on where emissions need to be, and they're committing to doing what's necessary to meet the goals,” Hiatt said. “But a lot of that sort of relies on this collective action from investment in other industries picking up the pace as well.”

The U.S. has never passed major legislation addressing greenhouse gas emissions despite decades of warnings about climate change from scientists, and the Supreme Court recently threw cold water on the EPA’s efforts to reduce emissions.

One area where there has been action is on disclosure from the Securities and Exchange Commission, which has proposed rules that would, among other things, require disclosures on scope 3 emissions for companies who set targets or those for whom the information would be “material” to the business.

RILA has opposed the rules in their current form. “A lot of aspects are challenging from a practical standpoint,” Hiatt said, who added that the industry group does support getting investors information but some of the SEC’s proposed “mechanisms and timing weren’t really based on what’s realistic right now based on reporting capabilities.”

Among the issues concerning RILA are all those discussed above — the difficulty in collecting comprehensive, accurate information on supplier emissions.

“I do understand the hesitation on scope 3 reporting because it's not like everybody's playing with the same amount of primary data all across the board,” Theisen said. “At the end of the day, though, we have to start somewhere.” Pressure to disclose, Theisen added, could force players to unify and act: “Maybe we all need our supplier data, and let’s create a coalition to get this data we need.”