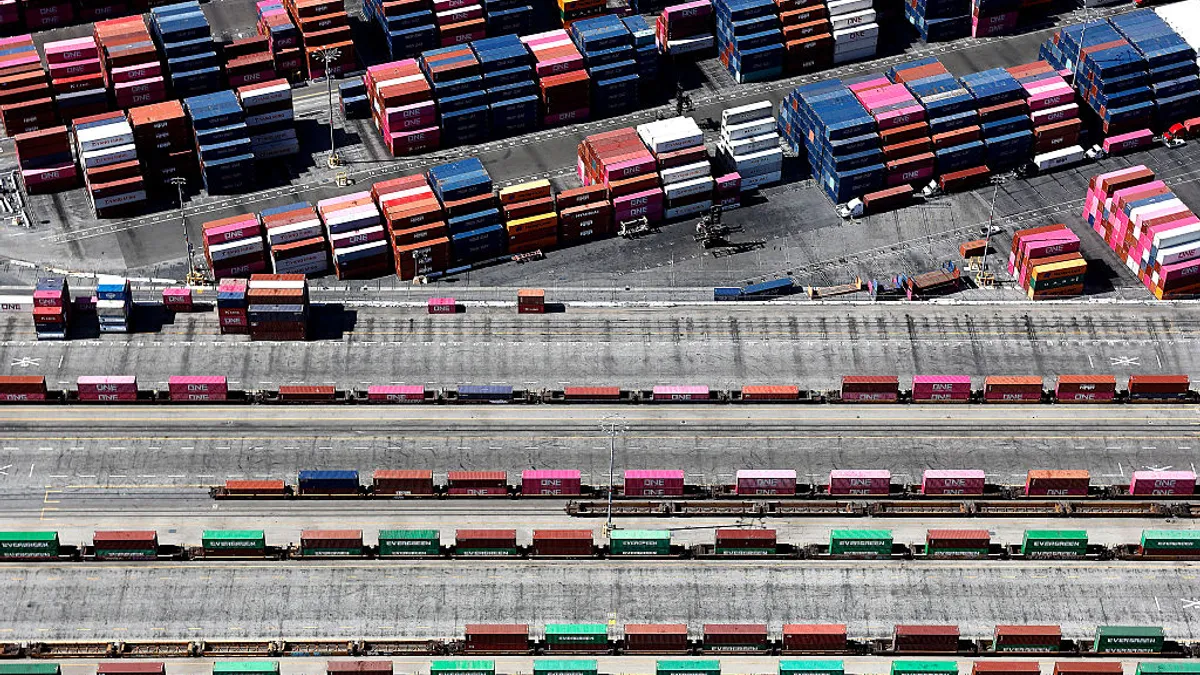

Automotive supply chains have had a turbulent couple of years, from the General Motors strike at the end of 2019 to the factory shutdowns in the early days of the coronavirus pandemic. Now, a semiconductor shortage with no quick fix is shutting down production lines around the world. Some experts expect the shortage to stretch into Q3 2021.

General Motors extended factory shutdowns into March as a result of the shortage. Ford said production in Q1 this year could fall by as much as 10% to 20% from the original plan. Overall, global automotive manufacturers could produce 672,000 fewer light vehicles in Q1, according to an estimate from IHS Markit.

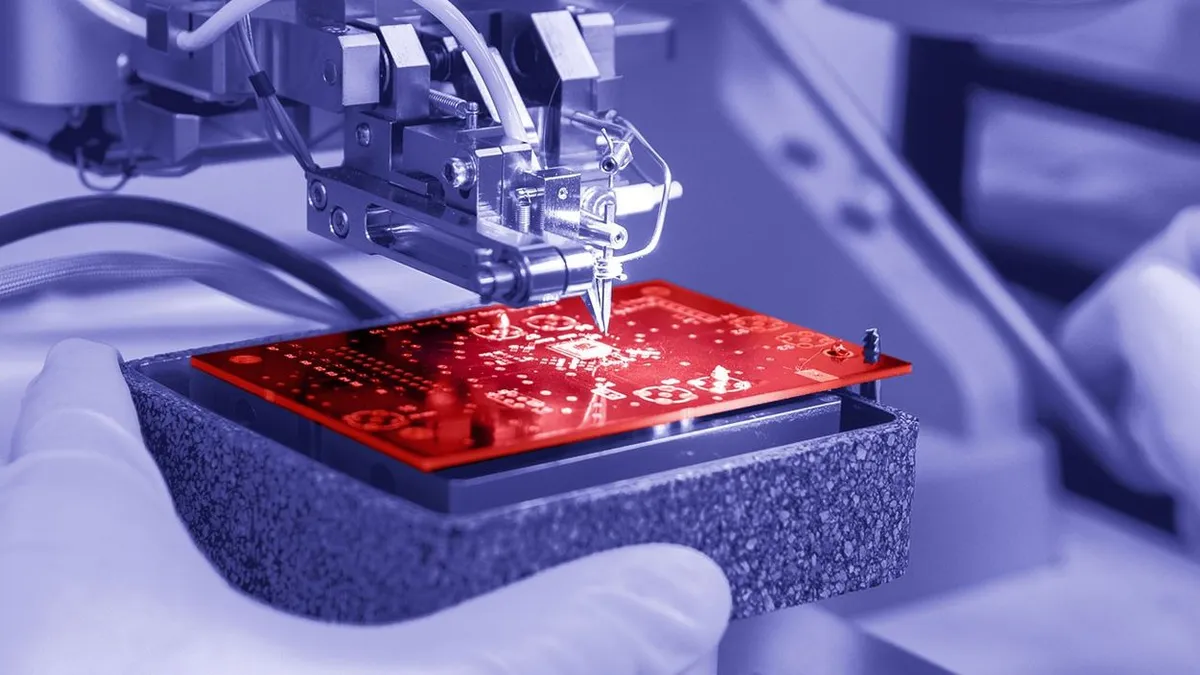

A shortage of semiconductors has resulted in a dwindling supply of microcontroller units, or MCUs, that are used in electronic control units, ECUs, throughout vehicles, from the engine and transmission, to the airbags and doors of modern cars. The shortage of such a vital component has sent supply chains scrambling.

"OEMs are trying to buy direct. Tier 1s are trying to find other sources if they can," Neal Ganguli, a senior managing director and leader of FTI Consulting's automotive and industrial business transformation group, said in early February. "But everybody's constrained because ... the bottleneck is at tier-3 level."

Automakers are obviously not the only buyers of semiconductors. And over the past year, demand has boomed as consumers purchase all sorts of technology, from goods to work from home, to the latest generation of gaming consoles.

When automotive companies are competing against technology companies for the same product from the same supplier, automakers could find themselves on the losing side of that fight, according to Amit Nagar, a partner at Bain & Company.

"The suppliers, they'll want to go to the other industries outside of automotive, and the reason is because automotive is a lower margin outlet for them versus the electronics companies," Nagar said, noting that many more iPhones, for example, are sold than any model of car.

Automotive is a fraction of TSMC revenue

One of the companies that manufacturers automotive MCUs, Infineon Technologies, said it has enough capacity to fulfill the confirmed orders, but demand has exceeded expectations.

"For 2021, we had factored-in some growth in automobile production and planned accordingly," a spokesperson said in an email, adding that Infineon is also investing in more capacity. "Due to the long lead times in the semiconductor industry, any capacity expansion takes time; contract manufacturers' capacities are limited. This makes semiconductor shortages felt throughout the supply chain. The shortage is expected to last a few more months."

Infineon and other MCU manufacturers have outsourced large parts of their manufacturing to Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company and other companies, according to IHS Markit.

And getting more capacity won't happen overnight, Infineon CEO Reinhard Ploss said on the company's February earnings call.

"Foundry capacity, especially for microcontrollers, is a limiting factor," Ploss said. "It will take time to bring more capacity online."

Calling all tiers of suppliers

Auto manufacturers slashed orders from suppliers and reduced production when car sales plummeted early in the pandemic. Units sold dropped 47% YoY in April, according to figures from the Bureau of Economic Analysis. At the time, IHS Markit forecast a 22% drop in worldwide car sales for 2020, according to CNBC.

"I know for the auto industry itself, back in early '20, it looked pretty dire," said John C. Taylor, chair of the department of marketing and supply chain management at Wayne State University.

But as the year wore on and dealerships reopened, "volume didn't fall off nearly as much as people feared," Taylor said. Vehicle sales have rebounded close to pre-pandemic levels, and it turns out automakers needed components from suppliers after all.

As automakers began ramping up orders again, it became clear that procuring some of the vital technological components wasn't going to be easy — or, in some cases, possible.

Top MCU suppliers in the automotive market

"The client that I'm working with, they actually get on the phone every four hours with the OEM to be able to talk about ... the situation," Nagar said.

Automotive supply chain executives have been aware of the semiconductor shortage for the last year and were even working on it over the Christmas holiday, Taylor said.

OEMs are asking their suppliers to figure out a way to get them more of the components they need. But there's not much suppliers can do at this point in time, and they're passing the blame to their own suppliers, Nagar said.

"The choke is in tier 3 capacity, which is the foundry ... that is making the wafer that goes into these chips," Ganguli said. "That is the capacity that's constrained, and you cannot have that capacity overnight."

The industry has seen some hits to its production capacity, including a fire that hit a supplier at the end of 2020 and a winter storm that shuttered factories in the U.S. But most analysts said the shortage is simply a matter of unexpectedly high demand for semiconductors.

"The choke is in tier 3 capacity, which is the foundry."

Neal Ganguli

Senior Managing Director and Leader of the Automotive and Industrial Business Transformation Group at FTI Consulting

Foundries such as TSMC and United Microelectronics Corporation say they're working on expanding capacity. On TSMC's earnings call last month, CEO C. C. Wei said resolving the semiconductor capacity issue is the company's top priority.

TSMC manufactures about 70% of all automotive MCUs shipped, according to IHS Markit. This makes it hard for companies to find backup suppliers, because the largest MCU suppliers — Renesas, NXP, Infineon and others — have outsourced much of their manufacturing to TSMC or UMC, IHS Markit noted.

Michael Hogan, a senior vice president at GlobalFoundries, told The New York Times that it was "doing everything humanly possible to prioritize our output for automotive," but it provided lead-time estimates ranging between 20 to 25 weeks for new orders.

Prioritizing production

Unable to get all the MCUs they need to keep up with automotive demand, car manufacturers have had to make decisions about what product lines to prioritize, experts said.

One strategy is to allocate resources to the most profitable product, Ganguli said. But that's not always possible, because some units are highly specialized and can't move from one application to another.

Fiat Chrysler Automobiles has had to temporarily pause some of its Jeep production — its highest selling brand — as a result of the shortage. And Ford had to do the same for its popular F-150 line.

"The global semiconductor shortage is creating uncertainty across multiple industries and will influence our operating results this year," Ford Motors CFO John Lawler said on the company's most recent earnings call. "The situation is changing constantly, so it’s premature to size what the shortage will mean for our full-year results."

The question is how automakers can handle the chip shortage in the short term, as suppliers upstream build capacity. "Unfortunately the answer is, 'not much,'" Ganguli said.

Just-in-case versus just-in-time: The financial question

Beyond the short term, automakers are rethinking the way they manage inventory. Automotive and high-tech were the industries were most likely to consider increasing their inventory and safety stock, according to the poll results from Gartner's Future of Supply Chain: Crisis Shapes the Profession report.

And the current chip shortage could be part of the reason companies are reconsidering, Gartner Vice President of Supply Chain Research and Advisory Geraint John said.

But this isn't the automotive industry's first foray into supply chain disruptions. After the 2011 earthquake in Japan, automotive production plummeted in the country. Toyota's production fell 78% YoY in April 2011, and Honda's fell 80% YoY, according to figures cited in a 2015 paper by Hirofumi Matsuo, a researcher at Kobe University.

And it's worth noting that semiconductor sourcing was one of the issues following the disaster, and specifically it was one of the weak links in Toyota's supply chain, Matsuo wrote.

"In a sense, the severe consequence of disruption was caused by just-in-time and single-sourcing nature of operations," Matsuo wrote of what happened in 2011. "That is, in this case, usual mitigation tactics such as adding inventory and having multiple sourcing discussed above had not been taken by Toyota."

"Every time there's a crisis ... we've said 'maybe we should look at going to dual suppliers.' But everybody's always backed off."

John C. Taylor

Chair of the Department of Marketing and Supply Chain Management in the Mike Ilitch School of Business at Wayne State University

Still, neither the 2011 earthquake nor any other disruption has been able to shake the automotive industry of its single sourcing and just-in-time operations. The financial benefits are just too good, Taylor said.

With additional suppliers, fixed unit costs could increase 50% to 100%, depending on what it takes for new and added suppliers to ramp up, Taylor said.

"Every time there's a crisis ... we've said, 'Maybe we should look at going to dual suppliers,'" Taylor said. "But everybody's always backed off of those things immediately after the crisis. Same thing for keeping inventory low, having lean inventories."

Part of what makes lean inventory hard to shake in the work of automotive is how customizable the cars are to the customer. Each car coming down a line could be slightly different. Keeping extra inventory of every available option would be hard for manufacturers, he said.

"It's not enough just to say, 'You know what, I'll change, and I'll hold inventories, and we'll buffer everything with inventory,'" Ganguli said. "But now you have a financial impact on your business."