Editor's Note: This article is part of a series on the supply chain effects of changes to the ocean freight industry. All stories in this series can be found here.

Ocean cargo carriers are anxious for change.

A series of market trends over the past decade have led to a historic trough for many companies. Since 2015, the world’s most prominent carriers have suffered from depressed freight rates, industry-wide overcapacity and two years of declining profits.

It’s not because of a lack of demand, however. Quite the contrary, the need for ocean transport is growing alongside world trade, sluggish, but still on the upswing. Globalization is still at full-swing, and a rising middle class is boosting demand for the transport of a wider diversity of products, such as perishables.

The shipping industry’s current struggles, then, are self-imposed. It was due to a race to the top; a desire to undercut competition; a prisoners’ dilemma that ended, even, in bankruptcy for one major carrier. While low rates were beneficial for shippers, the instability and drop in service that came with them were not.

Fortunately, in 2016, the industry began to self-correct. Seven major mergers or acquisitions, one bankruptcy, and hundreds of scrapped ships later, the industry forged a new world of shipping in 2017. Below, we tell the story of how that happened.

The Panama Canal’s expansion remains a symbol of the new era

PANAMA CITY – June 26, 2016 — It was a massive, widely anticipated event: 25,000 people — from the heads of states to shipping executives — had gathered at the Panama Canal to celebrate the infrastructure event of the century.

“More than 100 years ago, the Panama Canal connected two oceans,” Jorge Quijano, CEO of the Panama Canal Authority said at the event. “Today, we connect the present and the future.”

The fanfare was worthy of the event. Panamanians and shippers around the world had been waiting for the moment since at least 2006, when the project was first announced. Now, shipments from Asia could travel directly to the Americas’ East Coast, promising greater opportunities and savings for shippers.

“Today, we offer the world new shipping options and trade routes,” Quijano said. In celebration, COSCO Shipping renamed its 9,472 TEU-sized “Andronikos,” as “Panama,” and sent it from Greece to make the first inter-oceanic voyage.

The sailing showcased COSCO Shipping's global ambitions with its Panamax-sized ship, as well as the Canal's ability to handle it. It was a voyage symbolic of the changes the shipping industry would behold over the next year, where events that economists had anticipated for half a decade would finally come to pass.

Big ships bring bigger alliances — and overcapacity

PORTSMOUTH, VA – May 8, 2017 – Less than a year from the Panama Canal’s announcement of expansion, the big-ship era arrived on the U.S. East Coast. This time, it dawned at the Port of Virginia with a call from the COSCO Development — a 13,092 TEU vessel whose journey began in China — and another public celebration from stakeholders looking for greater import opportunities.

However, much had changed in the year that passed since the Panama Canal’s expansion. Since at least 2006, it had become clear big ships would become the norm. Larger ships mean fewer sailings, lowering both fixed and variable costs. Meanwhile, as the effects of globalization rose and the world recession subsided, carriers knew the need for cargo transport would only increase.

Ports, carriers and waterways that failed to acknowledge this would fall behind. So, too, would carriers who did not adapt to the new seas.

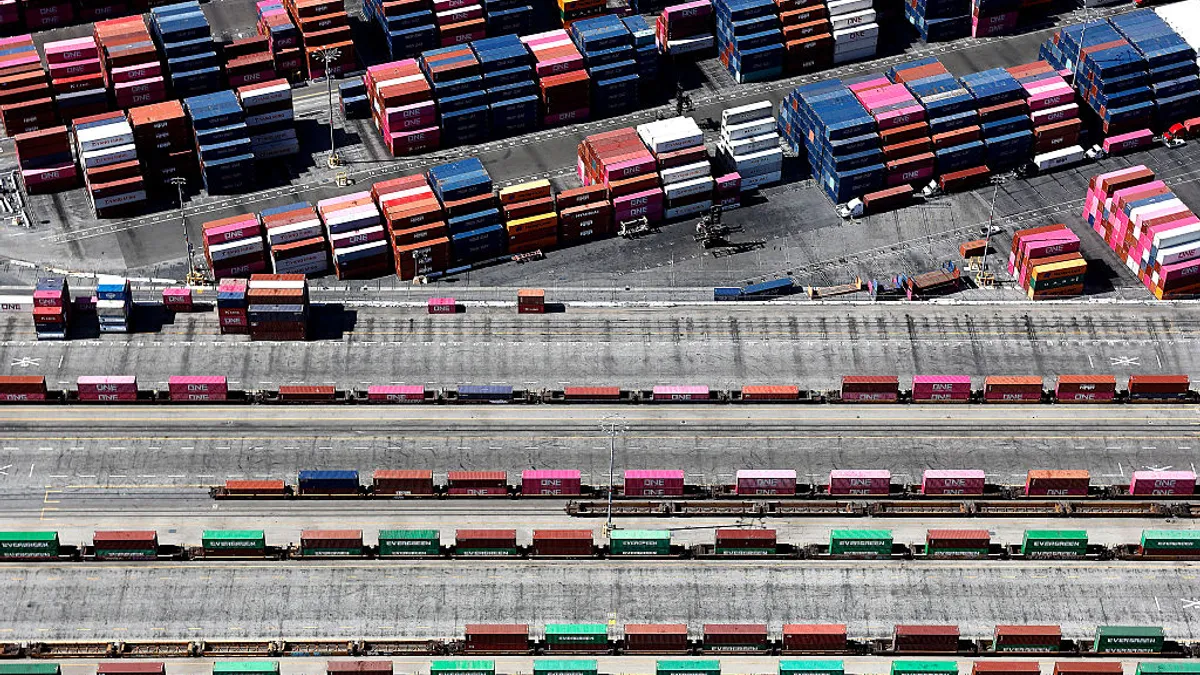

In turn, and in the advent of the big-ship era, carriers devised a series of strategies to build up their network and capacity while undercutting the competition. It was an arms race for economies of scale, the opportunity to transport more at lower marginal costs. Two tactics prevailed: order more big ships, and partner with other carriers to fill up those ships.

Over time, this market trend created an oligarchy within the industry. The industry only saw a 3% increase in capacity, but the top six carriers now control 68.1% of the industry’s market share. At the start of 2016, this same top-six group controlled only 49.9%.

This may sound like a success story, but it was truly the effect of an economic storm that created a sink-or-swim environment for carriers.

In a sink or swim world, carriers re-emerge anxious for profits

COPENHAGEN — May 11, 2017 — The mood on the earnings call was far more optimistic than it had been a few months prior. Back in February, A.P. Moller-Maersk's CEO Soren Skou had presided over a meeting to report the company's second-straight year of losses — the first time that had happened since World War II. The highlight? Maersk Line, the group's shipping subsidiary, was not alone in its suffering.

Poor financial conditions led even the world’s then-sixth largest carrier to bankruptcy, driving the world into a logistics frenzy and shipper confidence in the industry to all-time lows. For a long time, the question was not, “will this happen again,” but, “who’s next?”

"Seven carriers out of 16 or 17 so-called global carriers have or will disappear," Skou said at the time, listing the various acquisitions that had taken place over the last twelve months. Yet, he added that that was "a positive development for the industry." A degree of consolidation, he said, would help correct for the supply overcapacity that was responsible for low rates.

Today, it seems the worst has passed. "The container market is clearly improving," Skou said in the May earnings call.

The first half of 2017 has seen steady volumes and even more steady rates. Disruptions from new alliances, port strikes, or other one-off circumstances continue, but they have yet to cripple the industry. In fact, some analysts suggest the industry may recoup $5 billion in profits this year, or nearly the same amount that was lost in 2016.

But a strong recovery means shippers should take note and prepare for a sellers' market. After all, the shipping industry exists — like any other market economy — in a boom-and-bust cycle. After a trough is a steady recovery, and the low rates (and savings) enjoyed by shippers will slowly disappear, too.

And after this trough, a look at capacity and market figures reveals the global shipping industry reorganized into a sort of oligopoly. Perhaps that’s the price to be paid for stability.