This is a contributed op-ed written by Jonathan Welburn, an operations researcher at the Rand Corporation. Opinions are the author's own.

We’re in a disruption economy. Pandemic shortages, a weeklong blockage in the Suez Canal, the daily scourge of ransomware, all come from a common pain point: Global supply chains have become fragile. Isolated interruptions to individual supply chains feel like a thing of the past. Today, the risks are more likely to cut across supply chains and leave companies vulnerable to shared or cascading threats.

If we want to make supply chains more resilient, it's time to apply some stress tests.

The rationale for stress tests

After 2008 put systemic risks on full display, the banking world turned to stress tests as a tool for hardening financial networks against the next crisis. This might be the right tool for strengthening our supply chains, too.

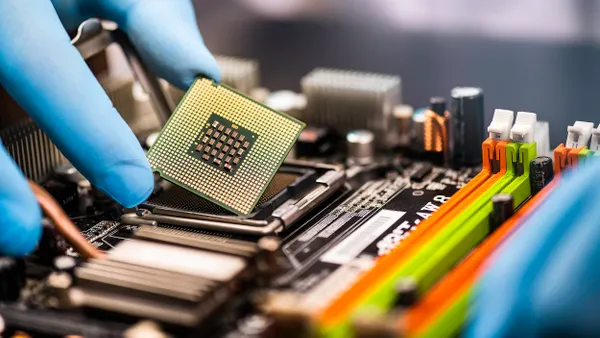

The networks behind our global economy are showing cracks. Automakers have cut production as they compete for chips in a global semiconductor shortage. Home builders are struggling to acquire enough lumber. And a second wave of COVID-19 cases in India constrained global vaccine supply. These incidents stem from misalignments in the pandemic economy, but they could have just as easily been caused by other forms of supply disruption.

Semiconductor production, for instance, is very heavily concentrated in Taiwan; the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company alone is responsible for more than half of the global chip supply. The chip shortage has highlighted TSMC as a central risk to supply chains should rising U.S.-China tensions threaten access to Taiwan. Taiwan faces severe climate risks, too, as a historic drought is affecting the water‑intensive fabrication process.

Cyberattacks have become a seemingly endless source of disruption. The Kaseya ransomware attack recently interrupted 1,500 organizations across the world. That came less than a month after an incident against JBS USA interrupted the global food supply chain and another cyberattack disrupted U.S. gas supplies. This wave of attacks spreading through software supply chains has no end in sight. And global supply chain networks allow each of these isolated shocks to spread and grow — a fact that makes them an appealing target for malicious hackers.

Building up to stress tests

The financial sector grappled with this brand of systemic challenge earlier than most. Stress tests had been used at individual banks prior to 2008, but the global financial crisis revealed their value for regulators looking to identify risks across bank balance sheets. The idea was to simulate banks’ performance under scenarios of rapid economic deterioration or "shocks" illuminating potential areas of risk that could cause banks to fail.

Stress testing supply chains would require new analytics infrastructure and expansive datasets.

Millions of firm-to-firm connections can be used to represent the network structure behind global supply chains. While these networks will be large, approaches similar to those powering Google’s ability to quickly rank search results across a network of hyperlinks can be used to rank firms on the network of supply chain links. Simulations of potential disruptions — large economic shifts, trade wars, climate change, or even cyberattacks — can then yield forward-looking assessments of risk.

Collecting the data will be a challenge, but not an insurmountable one.

Jonathan Welburn

Operations Researcher at the Rand Corporation

Collecting the data will be a challenge, but not an insurmountable one. Computing advances including analytical approaches to infer missing data and the large datasets sold by private vendors provide a start. Several recent government actions help build in supply chain transparency to enable stress tests. Consider President Biden’s creation of a supply chain task force, the Senate’s bipartisan support for rethinking industrial policy to counter China, and an executive order advancing the idea of a Software Bill of Materials.

No one can hold back the tide of industrial disruptions. Nor will stress tests predict the next major shock. But they can reveal where the next TSMC or SolarWinds might be hiding so that corporate supply chain and risk managers can prepare and decide which steps to take next.

This story was first published in our weekly newsletter, Supply Chain Dive: Procurement. Sign up here.