Supply chain managers have risen in importance over the last five years, and they will continue do so. Why? Data is improving, driving the need for a more thorough understanding of operations.

Better data allows companies to "peel the onion for improvement," Jim Fleming, program manager at ISM told Supply Chain Dive via e-mail. As data becomes more trusted and granular, and the emphasis on supply chain shifts, some key performance indicators (KPIs) are changing too.

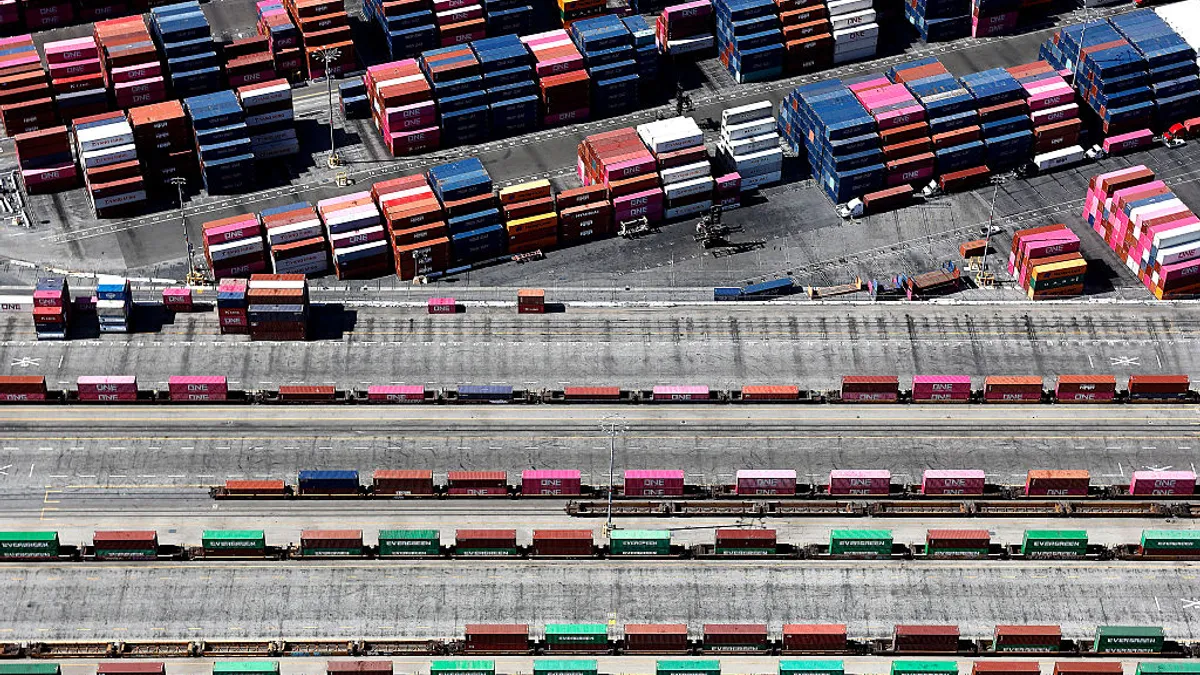

"Logistics grew up as a cost to be managed years ago. Now we’re finding that supply chain can be a revenue generator" if a company can manage its supply chain better than the competition, Rick Blasgen, CEO of CSCMP told Supply Chain Dive. That supply chain strategy might help companies achieve their goals by moving products to their shelves faster, for example.

Although analysts looking at publicly traded companies don’t care about most of the performance indicators behind the financials, a new wave of indicators is emerging to show investors and executives alike how well a company is doing.

Where analysts and operations managers diverge

Today, much of the focus in earnings calls is transportation-related. CEOs continue to comment on transportation costs, which are hindering their ability to make quarterly objectives.

Analysts, meanwhile, continue to look at output KPIs, like cash-conversion cycles and inventory days of supply. Or, perhaps, they may scrutinize a manufacturing company’s decision to shift its network through a different country, evaluating changes in supply chain costs. The focus on these output KPIs is important to investors measuring financial health.

In-house operations teams, however, focus on input KPIs, like overall equipment effectiveness and forecast accuracy, which helps drive decisions on how best to optimize the supply chain performance, according to an e-mail sent to Supply Chain Dive by Ildefonso Silva and Ketan Shah of McKinsey’s various supply chain practices.

“There’s a big focus on trying to get a deeper and better understanding of service.”

Jeremy Davidson

Director of Sales, Fortna

These indicators are better reflective of the current reality, because the data is more comprehensive, accurate and current.

"Now more than ever, there’s one version of the truth. Different data from different sources? Now we’re beyond that," said Blasgen. Companies are aligning their data so measurement comes from the same place.

Best-in-class? Not so fast.

Stakeholders outside the company, like analysts, investors or even supply chain partners, may have trouble evaluating different companies’ performance for a simple reason: to date, most companies have widely different key performance indicators.

On a fundamental level, there are about 10 KPIs that companies with top-performing supply chains use to measure and evaluate overall supply chain health, Peter Bolstorff, executive vice president at APICS, told Supply Chain Dive in an e-mail.

2 frameworks to measure supply chain efficiency

IDC's Simon Ellis looks at three KPI levels, based on operations level, using a top-down approach. Other frameworks, like the one used by Fortna's Jeremy Davidson, may look at KPIs based on function: whether the indicator measures cost, service or efficiency.

Framework 1: Metrics by operational level

| Indicator Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Board | The board should track high level indicators using no more than five or six KPIs, even though they’re not all related to supply chain. |

| Tactical | Ellis suggested measuring around 30 supply chain KPIs, erring on the side of fewer versus more. The number depends on the type and complexity of the business. |

| Operational | At this level, there could be hundreds or thousands of KPIs – with five or six metrics for every individual job. These are lower level job-specific operational KPIs, or even just “PIs. |

Framework 2: Metrics by operational function

| Indicator Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Cost | Using the analyst lens, these KPIs focus on cost structure, like direct or variable costs factored as a percentage of sales, or cost per unit. |

| Efficiency | "Historically the industry has focused on things directly tied to labor required to order, pick, pack and ship," said Davidson. Therefore KPIs include labor cost per unit, or per line pick. These KPIs look at the processing activity of work inside a distribution/fulfilment center or warehouse. |

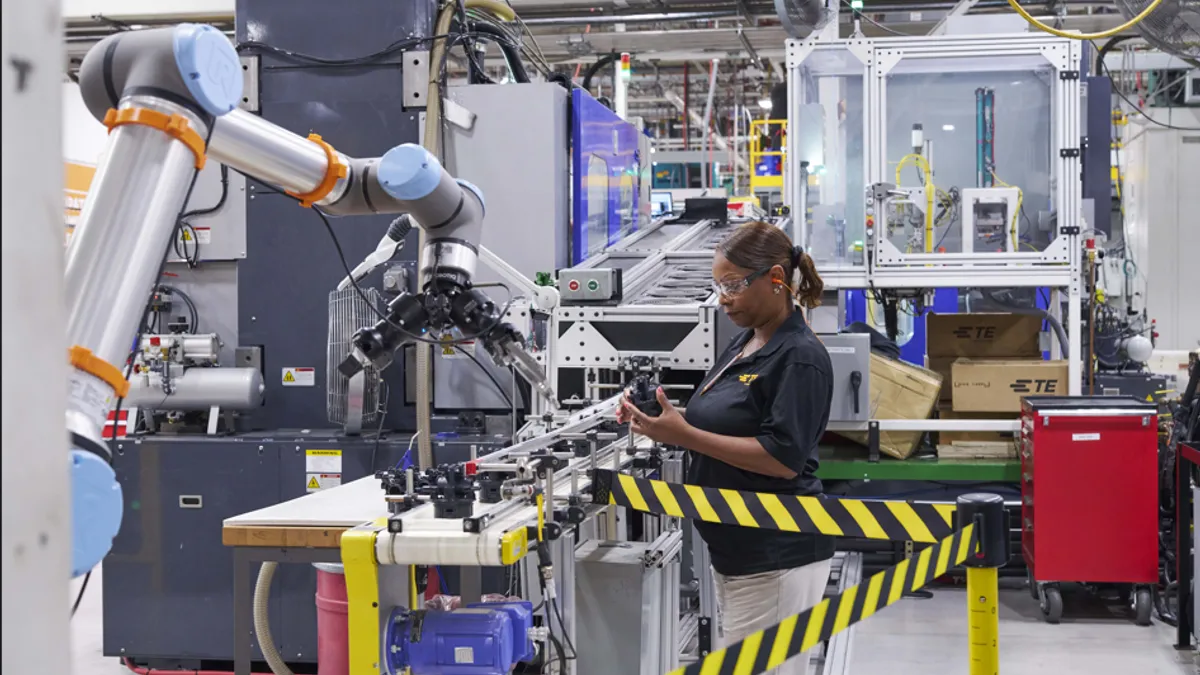

| Service | This category is newer, within the last few years. It includes cycle time, the time for orders to get processed in a facility and to compete against other highly service-focused organizations. As companies invest more in their fulfilment centers, automation and robotics take on increased importance in operation indicators. These KPIs factor that into service fulfilment, from the time the order is received to when it’s loaded on the truck. |

These include customer- and internal-focused key performance attributes such as reliability, responsiveness, agility, cost and asset management efficiency. Their analysts then track back to each attribute with strategic metrics including perfect order fulfillment, order fulfillment cycle time, upside and downside adaptability and cash-to-cash cycle time, among others.

Simon Ellis, program vice president of IDC Manufacturing Insights, contends that the fundamental metrics KPIs measure haven’t changed over time; rather, expectations for increased performance are changing.

A new generation of KPIs

As supply chain takes on increased importance, some newer KPIs figure more prominently too, according to conversations with various analysts.

- Disruption impact: A supply chain’s resilience is more important now, whether due to a hurricane, strike or other conflict. Companies are measuring how quickly the supply chain can recover and what that means to the business, said Ellis.

- Working capital management: “In the low-inflation environment we’ve been in for most of the past four decades, tying up cash in working capital has been less of a focus,” said Jim Barnes, executive managing director at ISM in an e-mail. “With the prospect of higher inflation on prices and higher borrowing costs, working capital is beginning to gain focus again.”

- Return on capital investment: Analysts are watching supply chain investments in fulfillment, and they want to know how resources or investment initiatives are improving a company’s ability to compete. A KPI measuring time from order to customer delivery is important.

On earnings calls, analysts may ask about direct-to-consumer investments and the company’s expectations to deliver goods in a day or two and not have individual orders carry over, as they might have in the past.

These new KPIs help analysts understand whether companies can make commitments that are on par with their competitors, Jeremy Davidson, director of sales at Fortna, which designs and implements solutions at fulfillment centers.

"An analyst would be interested to know how much capital investment they need to compete, as they raise the service level and leverage cost structure," Davidson told Supply Chain Dive. "They’re looking at the return on invested capital and what they’re getting out of investments on operations."

Recently, companies started looking more closely at what can and cannot be fulfilled in a day. Whereas it used to be a goal to get 75% to 90% of orders out the same day, now it’s more like 98%. In the consumer’s mind, everyone should be able to meet that goal.

As a result, internal teams have also begun to look at a distinct set of operations indicators:

- Queue time: Automation has changed the labor process, focusing less on labor and more on how much time the equipment is available for processing. "People are actively measuring the queue, the available capacity of the equipment as a KPI, to understand the flow and balance of an asset like a piece of equipment in an operation in a given day," said Davidson. The KPI might be a percentage of orders in the queue versus total capacity, or the time to process the order against the available capacity. Or it might be the available equipment uptime and backup equipment to handle excess need.

- Customer expectations: Companies need to ensure they’re measuring what’s important to their customers, not just things that are easy to measure.

- Return logistics: As e-commerce and omnichannel sales increase, analysts should start asking questions about return logistics, said Silva and Shah. That would include the percentage of goods returned online and the health of inventory, which signals potential write-downs and write-offs.

Not all industries are alike

KPIs differ by industry and what’s important to them.

A high-tech company or even a fashion accessory company with short product life cycles need to get the product on the shelf quickly, before the product loses its hype. In that case, KPIs would include time to market, time to volume, and time to ramp up production quickly, based on demand. The window for an on-time delivery depends on the industry.

"Such differences can be quite pronounced across industries and are a function of specific industry dynamics," wrote McKinsey’s Shah and Silva, like the same delivery reliability for e-commerce is different than what’s needed in industrials.

Healthcare companies would be primarily interested in making sure everything is shipped in a timely manner, so they have time to stock the needed products. Availability is more important than productivity measures. A high value luxury brand might have KPIs focused on the item presentation and packaging, and less on productivity, said Davidson.

In retail, the most important KPIs Oliver Chen follows are customer acquisition costs, customer retention versus acquisition trends, and customer lifetime value. Chen is Cowen’s managing director for consumer, retailing/department stores, specialty softlines and luxury.

However, all supply chain managers need to make the KPIs count. "It is always wise to not measure too many things and not measure things that are mutually exclusive," Ellis said.