Shippers are facing yet another disruption as the year comes to an end, as the Suez Canal becomes a less viable route to move cargo.

Earlier this month, attacks on vessels traveling to the shipping channel through the Red Sea led major carriers to reroute ships or halt transit. And while an international operation is being coordinated to help secure safe transit for commercial vessels, logistics managers now find themselves assessing contingency plans until the situation is resolved.

Supply Chain Dive spoke to several shipping and logistics experts about some of the concerns shippers may have given the current situation. Here's five questions and answers that may help shippers decide where, how and when to reroute their cargo.

1. How are carriers responding?

Carriers are acting fast given the potential of Houthi-led attacks on cargo ships.

Beginning Nov. 19, about 55 vessels were rerouted through the Cape of Good Hope route, "which is a significantly low number when compared to the number of 2128 vessels transited the Canal in that period,” according the Suez Canal Authority. In 2022, 23,851 vessels transited the Suez Canal, with an average of 68 ships per day.

Longer transit times are expected in the medium term for shipments that have not departed, Nathan Strang, director of ocean freight, U.S. Southwest and SMB at Flexport, wrote in a Tuesday LinkedIn post. "How much depends on what the vessels' original routing was and when the vessel diverted. Keep in mind that some of these vessels were already diverted away from the Panama Canal," he added.

Actions from ocean carriers in response to the vessel attacks

| Ocean Carrier | Action Taken | Surcharges | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maersk | Instructing all Maersk vessels in the area bound to pass through the Bab al-Mandab Strait to pause their journey until further notice | Emergency Risk Surcharge, effective Jan. 8, 2024 | |

| CMA CGM | Rerouting several vessels from their intended route through the Cape of Good Hope | Several surcharges: A RED SEA surcharge, effective Dec. 20, and a contingency surcharge effective immediately | |

| Hapag-Lloyd |

|

War Risk Surcharge, effective Jan. 1, 2024 | |

| MSC | MSC ships will not transit the Suez Canal Eastbound and Westbound and instead will use the Cape of Good Hope | Contingency Surcharge, effective Dec. 23 | |

| ONE Line | Rerouting vessels away from the Suez Canal and the Red Sea using the Cape of Good Hope | None as of Dec. 20 | |

| Evergreen | Temporarily suspending Israeli cargo and rerouting vessels via the Cape of Good Hope | None as of Dec. 20 | |

| OOCL | Temporarily suspending Israeli cargo | None as of Dec. 20 | |

| ZIM | Began rerouting some of its vessels in late November from the Arabian and Red Seas | War risk premium surcharge, effective Nov. 22 |

SOURCE: Ocean carriers

2. What alternatives exist?

Shipping lines can use the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa to bypass the Suez Canal.

However, the safer alternative for shippers comes with extra costs and transit times. A trip from Singapore to Rotterdam around the cape is an extra 3,500 kilometers by container ship, Michael Zimmerman, partner in the strategic operations practice at Kearney, a global management consulting firm, said in an email.

"The extra fuel will cost an additional $500,000 to $1,000,000 and shippers have the inventory on their books [for] an extra 20-30 days," Zimmerman said.

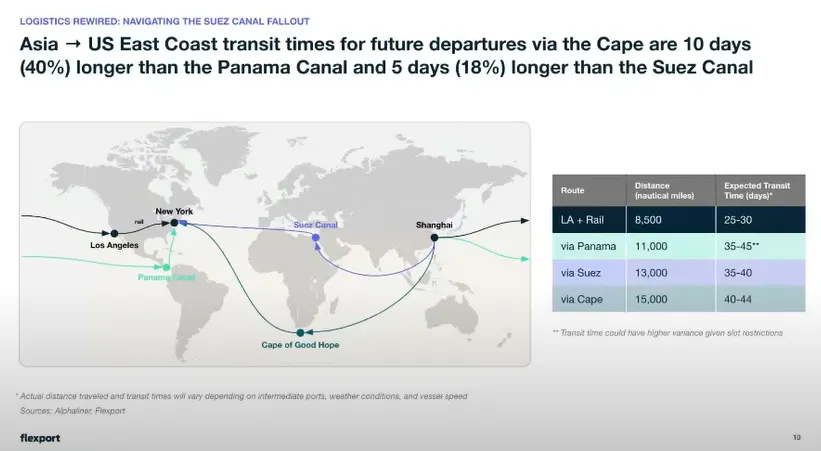

On the Asia to U.S. East Coast route, shippers could also switch modes, leveraging truck and rail intermodal moves from the U.S. West Coast, Strang said during a Wednesday webinar.

However, other experts pointed out these are also imperfect solutions, as shipments will be delayed in either case. In emails, forwarders told Supply Chain Dive they were working with customers to assess near-term freight risks, and redirect customers to alternative routes.

C.H. Robinson Operations Supervisor Matthew Burgess said their plans include a combination of sea and air solutions via Colombo, Dubai or the U.S. West Coast, in addition to traditional airfreight solutions and expedited inland services once cargo arrives at port. Meanwhile, a Kuehne+Nagel spokesperson said the company was encouraging customers to use a sea-to-air solution, where eastbound shipments could arrive from Asia by sea to Dubai, then transit by air.

“This allows for a faster transit time compared to sea freight and a more sustainable and cost-effective solution than direct air freight,” the forwarder said in an emailed statement to Supply Chain Dive

3. What could happen to ocean freight rates?

In a weekly emailed update, Freightos said rates will almost certainly increase from Asia to Northern Europe.

Ocean carrier ZIM, which began diverting its vessels that normally use the Red Sea last month, increased rates for its Asia to Mediterranean service. Now, shippers must pay between $3,300 and $3,400 per forty-foot equivalent unit for the service, according to Freightos.

Spot rates are also increasing already. Rates from Asia to the U.S. East Coast and West Coast have already increased slightly and more are likely to come, Lars Jensen, CEO and partner at Vespucci Maritime, said in a Thursday LinkedIn post, referencing Drewry's WCI Index. However, he also said the rates remain comparable to levels seen earlier this year.

So while rates are rising, experts said readers should not expect them to increase as severely as they did the last time the Suez Canal was blocked for a prolonged period, in 2021.

“Because of the excess capacity available to address the disruption – something that was not the case during the Suez Canal blockage in 2021 – it is possible that the industry will avoid the extreme rate spikes like those seen during the pandemic,” Freightos Head of Research Judah Levine said in an emailed update.

4. What goods could be most affected?

During the 2021 blockage, experts told Supply Chain Dive nearly everyone may be affected in some way, given the size of the trade route. And companies like Walmart and Ikea, as well as the automotive and technology industries, may be particularly exposed.

The Suez Canal is a critical artery for the Asia-Europe trade, which represents 12% of vessel routes and 30% of global container traffic, according to Lawson Brigham, a retired U.S. Coast Guard captain who wrote about the topic in the U.S. Naval Institute's Proceedings Magazine issue.

As a result, experts said the Asia to Europe trade lane will likely be most affected, as it is the shortest sea route available.

“The market anticipates that especially in Europe which is on the receiving end of import containers from the Middle East, India, southeast Asia and China, that container scarcity will lead to an increase in container prices and the market," Christian Roeloffs, CEO and founder of Container xChange said in an analysis shared with Supply Chain Dive.

In the U.S., goods sourced from Asia – such as apparel, toys and electronics – and shipped to the East Coast may also be affected, Srini Rajagopal, VP of logistics product strategy at Oracle told Supply Chain Dive. Exports from the East Coast, like grains, liquified petroleum gas and liquefied natural gas, may also be affected.

However, any commodity that can be shipped using alternative modes, such as air, may be safe from severe disruption. Zimmerman said the list is small, though, and “only the most expensive goods that move by air or domestically produced and consumed goods or goods that can move internationally by truck will remain unaffected.”

5. What else should shippers know?

Shippers considering shipping from Asia to the Gulf Coast need to be aware that the trade lanes may also be subject to delays due to ongoing drought restrictions at the Panama Canal.

"The Panama canal is still experiencing a drought which is resulting in less vessel slots being available on a daily basis," Anders Schulze, SVP and global head of ocean freight, at Flexport said during a webinar. "The number of slots are expected to decrease going into February, so the Panama delays could increase over the next 6-8 weeks."

Besides tackling alternative shipping routes, shippers should also look into material sourcing strategies, Rajagopal said.

“This includes multi-sourcing (using multiple suppliers for a certain material in case one of the suppliers is unavailable) and sourcing materials in-region (using sources that are physically closer to the manufacturing hubs),” Rajagopal said.

In addition, shippers should be wary of their insurance premiums.

While there are some small niche carriers that can offer shippers an Asia to Mediterranean service route using the Suez Canal, shippers need to realize this comes with a risk, Jensen said during a Flexport webinar on Wednesday.

“You do risk losing your cargo, but I would also read insurance premiums extremely carefully to see if you are covered in a situation where the risk is this obvious," Jensen said. "I would not be surprised, as some might find it impossible to get their cargo insured at all.”

Kelly Stroh contributed to this story.