The old saying, "What goes up, must come down," is widely applicable, from a baseball tossed in the air to aspects of the market.

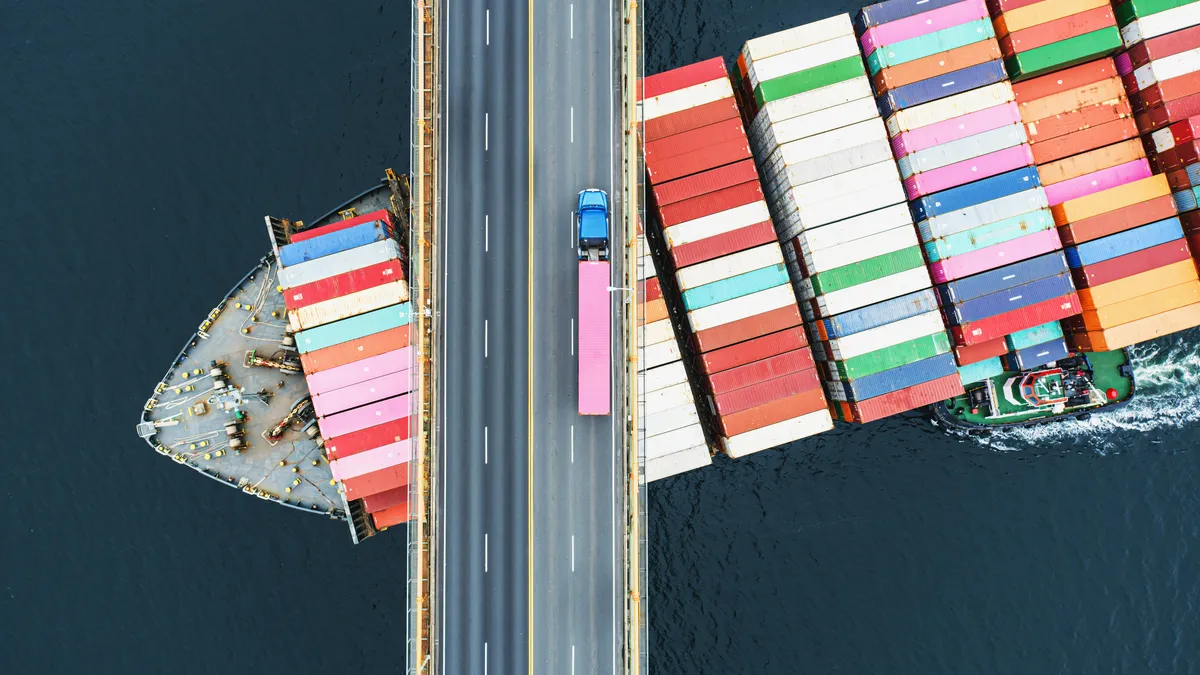

Trucking prices are currently in the "up" stage, not yet ready to fall. In the meantime, shippers are looking for alternatives — and their eyes are on the rail yard.

Long a competitor with trucks, trains once moved the majority of long-haul freight in the United States. By 1978, rail's share of intercity freight dropped to 35%. Today, trucks dominate, hauling about 80% of freight, said Tim Denoyer, ACT Research vice president and senior analyst.

But when truckload capacity is tight and spot rates go high, as they are now, shippers give train and intermodal transportation another look.

A surge in imports from Asia, arriving at California ports, is partially fueling the current market dynamics, said Denoyer. U.S. imports are up 34% from May, driven by consumer demands that grew consistently after the initial stage of the COVID-19 pandemic in the spring and retailers' needs to replenish inventories, Denoyer said.

Trucks would normally handle most of the imported freight over long hauls, from ports to inland points in the United States. But trucking has been bedeviled with snags in meeting stronger demand. The factors range from the pandemic to a driver shortage.

The multiple issues, positive and negative, mean TL spot rates are up, translating into higher prices for shippers.

Trucking's upper hand: speed and visibility

Higher prices are helping intermodal companies and railroads get more freight business. But it's usually not the kind of freight that needs to get somewhere soon, said Dean Croke, DAT principal analyst.

"If you have a load that doesn't need to be anywhere in a hurry, you put it on a train," said Croke. And rail freight is cheaper because of that.

But only some types of freight translate easily between road and rail. Dry goods in containers are typically ideal for trucks, and they are also easy work for trains. They include consumer goods such as clothes, electronics, sporting goods and toys — almost anything that can go inside a container can be hauled in a dry van.

Liquid cargo and refrigerated goods can be transported via intermodal, too, said Jim Blaze, a railroad analyst and former Conrail employee.

"If you have a load that doesn't need to be anywhere in a hurry, you put it on a train."

Dean Croke

Principal Analyst at DAT

Intermodal makes sense if there is a longer lead time, Croke said. Shippers are already thinking of next spring, and they want to stock up "because the pandemic is still with us," Croke said. Pulling inventories forward is an ideal scenario for intermodal.

"You can let it sit in the rail system for a longer time," Croke said.

Highly regulated cargo, such as manufactured chemicals and hazardous materials, don't make good intermodal cargo, Blaze said, although there are some exceptions. Large, wide cargo is usually handled solely by flatbed trucks, although some railroad companies can make exceptions.

There are also factors to weigh in jumping to rail. Shipping via rail provides less visibility, at least for the shippers.

"The railway knows exactly where your freight is," said Nick Little, director of railway education at the Center for Railway Research and Education at Michigan State University, speaking to a room full of shippers at the APICS conference in Chicago in October 2018. "They don't tell you."

Visibility is indeed a problem, said Blaze. Automatic identification tags attached to rail freight have helped speed up data entry for railroads, but those depend on the products moving past fixed scanners that use radio-frequency beams to catch freight at various points, a process Blaze calls "interrogation." That process is often delayed because freight has to move past the scanners to be tagged.

With most trucks, GPS devices are always transmitting in near-real time.

"You have instant, continuous communication" with trucks, said Blaze. "With railroads, you have occasional communication."

A tale of 2 tight markets

Many shippers have opted for intermodal transport, and spot rates have risen along with the demand. Intermodal spot rates were $1.74 per mile at the beginning of October, compared to the monthly average of $1.31 in May, according to Croke.

Overall, U.S. railroads originated about 1.4 million intermodal containers in September, an increase of more than 7% YoY, according to the latest numbers from the Association of American Railroads. The AAR said September was the fourth-best intermodal month in history.

"The railways are moving as much as they can," said Croke. "And just like trucking, the volumes have been imbalanced."

"Railroads are not going to go out and seize 10% market share from trucking, because they just don't have enough equipment capacity."

Jim Blaze

Railroad analyst

Part of the imbalance stems from the fact that it is even harder for railroads to add freight cars. It takes between 12 to 18 months to order and get a freight car, said Blaze. Fleets can walk onto sales lots and buy almost-new or used trucks immediately.

"Railroads are not going to go out and seize 10% market share from trucking, because they just don't have enough equipment capacity," Blaze said.

The railroads have responded by not always quoting rates, Blaze said, because they are so overwhelmed by shrinking capacity.

"Both markets are tight now," Denoyer said, referring to trucking and rail. "What's going on is just a big restock."

It's quite a turnaround for railroads. Denoyer said rail volumes were down for seven quarters in a row, until the numbers went positive in the first week of October. Intermodal spot rates for the first week of October were up 61% from the same week in October 2019.

Part of the reason for the jump in spot is the $5,000 peak surcharge that Union Pacific placed on excess contract cargo on Aug. 30, Denoyer said. The surcharge was an attempt to manage demand.

But weeks later, consumer demand is still in the driver's seat. The volume of loaded TEUs coming into U.S. ports since Sept. 1 is up 6% YoY, Denoyer said. That volume usually ends up on a truck or train. The question for shippers is: Which is best, in a freight market where trucking capacity is cramped and where intermodal takes longer?

Blaze said selling TL services to shippers over their rail competitors is a relatively easy task. Intermodal and rail can take longer. Trucks are not inhibited by fixed rail routes. Trucks also have better visibility.

Croke said trucks have the upper hand — especially if lead times are tight.

"Shippers look for service and price," said Croke. "A single driver can get to [a destination] quicker than the fastest train."