This is a contributed op-ed written by Karen Conway, vice president of Healthcare Value at Global Healthcare Exchange. Opinions are the author's own.

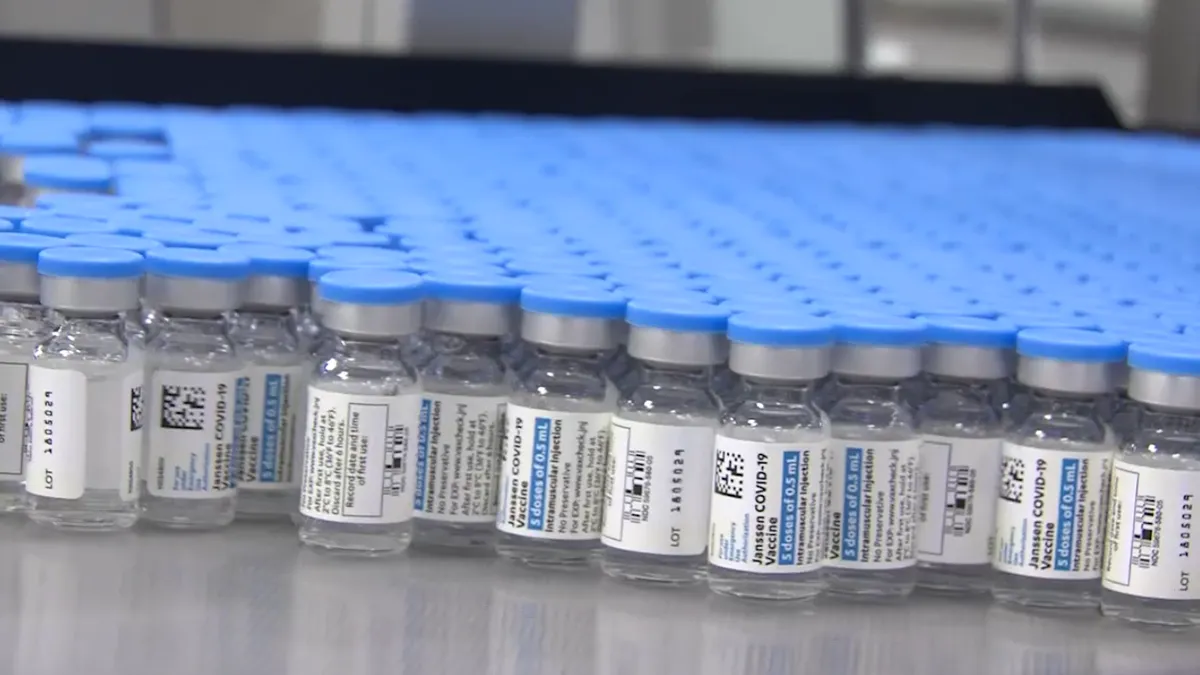

As approved COVID-19 vaccines roll off production lines, and millions of Americans roll up their sleeves, we are witnessing a modern-day miracle.

The development and approval of three separate, effective vaccines in the U.S. in less than a year appear to be nothing short of miraculous.

But the real modern-day miracle may be in overcoming the logistical challenges of delivering three different vaccines. Each comes with different handling instructions and dosing requirments, and every state has varied eligibility criteria and distribution channels. As any student of quality knows, variation increases the chances of errors.

Distribution variations create challenges

The variation in the different handling and dosing requirements is understandable. What is less explicable has been our willingness to introduce unnecessary variation into the system (having each state handle distribution differently) and our reluctance to use the commonplace tools at our disposal, such as barcodes, that can significantly improve the efficiency and safety of the vaccine supply chain.

The variation started at the top when the federal government gave a mandate to General Gustave Perna, the chief operating officer for Operation Warp Speed, to deliver the vaccines to the states and no further.

A professional colleague of General Perna’s, retired Major General Vinny Boles, said if the orders had been to get the vaccines into people’s arms, General Perna would have met that goal with far less variation. In his words, we are fighting a war (against the virus), and when you go to war, you send in the federal troops, not state or local. Instead, it has been a state-by-state battle.

Some states deploy the national guard, others utilize chain and independent pharmacies, and still, others rely on local health departments to deliver the goods, or a combination thereof. Based on early results, states that deployed the national guard, which has clinical and logistical expertise, seemed to fare better than those relying on local health departments with good clinical expertise but little to no supply chain experience. Surprisingly, very few states leveraged the expertise among the supply chain professionals that operate in hospitals across the nation.

Barcodes for supply chain logistics

Perhaps most disappointing has been the failure to use one of the most common tools for supply chain logistics: the barcode.

All three manufacturers have included barcodes on the vaccines, but only at the secondary packaging level. That means the ability to scan the barcode is lost if a box or case of vaccines (which could include 1,000 doses) must be distributed in smaller quantities, say to a rural community. All documentation, including which patient received which vaccine, where and when, and the associated storage conditions, must be handled manually, which is far more error-ridden.

Patients receiving one of the two-dose shots from either Pfizer or Moderna must also retain a piece of paper with handwritten notes as to which vaccine they received to ensure they receive the correct follow-up inoculation at the appropriate time and place. Proper documentation is also vital in monitoring for adverse event reactions.

Accurate and detailed information is needed to determine root cause: was it the drug itself, or just a bad batch? Was it due to poor handling or something related to a patient's factors? This level of drug safety is essential to demonstrate efficacy (i.e., how the product performs in routine practice, not just in clinical trials) and to improve public turnout for vaccination.

Create multi-directional visibility. Many of the supply chain challenges during the pandemic were exacerbated by a lack of visibility into inventory and demand.

So why not use the barcodes at the primary packaging level? Several pharmaceutical manufacturers have told me that adding barcodes at the primary packaging level would strengthen the vaccine supply chain's integrity and efficiency but at a cost. Those same manufacturers added that if something is not mandated in a highly regulated industry like healthcare, it is often not funded.

Devendra Mishra, executive director of the BioSupply Management Alliance, is both energized and disappointed.

"We have seen remarkable speed in the development of the vaccines, but not the same speed or capability in the supply chain itself," Mishra said. For him, extending the collaborative spirit behind vaccine development into the supply chain is needed to prepare for the next pandemic or major threat to supply chain continuity. With collaboration comes greater visibility across the supply chain and into the myriad factors that impact supply chain performance.

Case in point: dry ice is critical to the vaccine cold chain, but its production is also dependent upon ethanol production, which produces carbon dioxide, one of the ingredients in dry ice. With people driving less, ethanol production has declined along with the supply of dry ice. As supply chain professionals know, the supply chain is only as strong, only as resilient as its weakest link.

5 best practices for vaccine distribution

There are five best practices we can glean from lessons learned during vaccine distribution.

1. Minimize variation whenever possible. Some degree of natural variation will always exist. But the key is to minimize variation that we can control, such as who is eligible for the vaccine, how it is distributed and how it is identified and tracked across the supply chain.

2. Leverage the tools we have. Most pharmaceuticals and medical devices have an auto-identification carrier (e.g., a barcode) to support electronic vs. manual capture of product information. But like my treadmill, barcodes are only of value if you use them.

3. Invest in automation. Scanning barcodes on patients and medicines has become the standard operating practice in healthcare. It's been proven to reduce medical errors while reducing the amount of time spent by clinicians on clerical tasks. It should be how we document the movement and use of all products across the supply chain and in patient care.

4. Create multi-directional visibility. Many of the supply chain challenges during the pandemic were exacerbated by a lack of visibility into inventory and demand. Due to the interdependencies of the supply chain, this visibility needs to extend upstream into raw materials, downstream into forecasted demand at all locations where care is delivered and across to the sources of various supplies and products upon which supply chain operations depend.

5. Call on the experts. When meeting critical supply chain challenges, call on the experience and expertise of supply chain professionals working every day in hospitals across the nation. These experts manage spend that rivals the size of major corporations and facilitate the sourcing and delivery of a wide range of products to meet their patient population’s various health needs. They know healthcare, they know supply chain and they know the communities they serve.

This story was first published in our weekly newsletter, Supply Chain Dive: Operations. Sign up here.