While the cause of the fire on the Maersk Honam is unknown at this point, it's one of a spate of fire disasters at sea that cost lives and caused property damage and supply chain interruptions. Five seamen died as a result of the March 6, 2018, blaze on board.

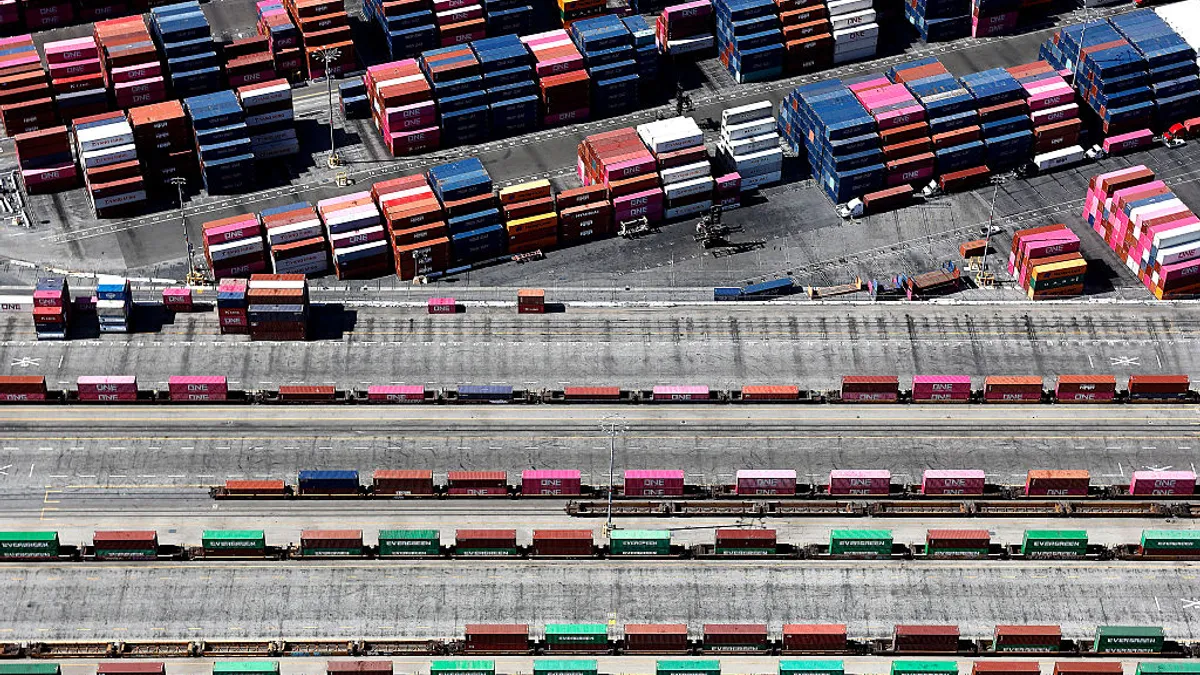

Shippers who had cargo on the Maersk Honam may have not only lost products in the fire but will also have to share in the costs of the disaster under a maritime legal principle known as General Average. That's one of the risks of vessel fires and other hazards at sea that can disrupt the supply chain and leave shippers holding the bill.

Cargo owners must provide proof of bond for the General Average costs and for salvage security before they are allowed to receive their cargo, according to average adjuster Richards Hogg Lindley.

While the damaged vessel moved slowly toward port, shippers did not know the state of their cargo and could not adjust their supply chains accordingly. Any just-in-time shipments were undoubtedly behind schedule.

Shippers must prepare for risks of vessel fires

It's an axiom of the sea that there's no greater fear than a fire onboard a ship.

In 2016, 85 vessels of 100 gross tons or more were declared a total loss, and eight of those were due to fire/explosion causes, including one case of suspected arson, according to the Allianz 2017 Safety Shipping Review. From 2007 to 2016 fire/explosion was the third most common cause of total losses, behind foundered and wrecked/stranded.

Fires are the third greatest cause of vessel loss

| Cause of ship loss | Number lost from 2007-2016 |

|---|---|

| Foundered (sunk, submerged) | 598 |

| Wrecked/stranded (grounded) | 244 |

| Fire/explosion | 118 |

| Collision (involving vessels) | 72 |

| Machinery damage/failure | 71 |

Source: Allianz Safety and Shipping Review 2017

With the trend toward larger vessels, any disruption in a single voyage has a significant ripple effect throughout the supply chain. Despite overcapacity in the market, industry experts see continued deliveries of container vessels of 20,000 TEUs or more. The larger ships increase exposure to damage, liability, environmental impact and salvage costs. Allianz predicts a casualty cost in the $2 billion to $4 billion range if a large container ship or tanker were to be lost in an environmentally sensitive area.

How shippers contribute to fire risks

Fire risks vary for different types of vessels, of course. Engine room problems are shared across all types. Given their cargoes, oil and gas tankers face their own set of issues. On container ships, the most significant risk comes from misidentified cargo.

"Fire prevention and firefighting strategies both depend on accurately knowing the contents of the dangerous goods container," Smarty Mathew John, technology manager for the American Bureau of Shipping told Supply Chain Dive in an email. "Misdeclared or insufficiently declared cargo could lead to incorrect stowage and segregation thereby increasing the potential for fires as well as incorrect firefighting or emergency response in a fire event."

Allianz estimates that up to one-third of boxes containing dangerous goods are not appropriately labeled, and one-fifth may have some other problem. Whether a box is mislabeled by accident or deliberately to avoid higher rates for dangerous goods, a container that crew doesn't know is carrying dangerous goods can lead to disaster.

If the crew does not have an accurate understanding of the cargo in the box, the box could be loaded deep in the ship where it will be difficult to reach in case of a fire or on top of the engine room where it is subject to excessive heat. If the cargo does catch on fire, the crew won't know what they're dealing with and could make the fire worse. Some chemicals react violently to water for example, and those fires must be fought with foam instead. Electronic devices that use lithium-ion batteries present a high level of risk on a vessel for the same reasons they're not allowed in checked luggage on aircraft.

All vessels share some risks

Container ships aren't the only vessels at risk. Carriers of bulk commodities such as coal, direct-reduced iron and certain bulk solids face risks from combustion, according to the Swedish Club. Car carriers, or roll-on roll-off, AKA ro-ro vessels, have risks because of the varying nature of the cargo they carry.

For example, on June 2, 2015, the ro-ro carrier Courage was loaded with about 6,000 vehicles including BMWs and Mercedes as well as privately owned vehicles of U.S. government employees and service members when it caught fire transiting from Bremerhaven, Germany, to Southampton, United Kingdom.

One of those vehicles was a 2002 Ford Escape SUV that had been subject to several recalls, including one for brake fluid leaking onto the automatic braking system wiring harness, a known defect that caused electrical fires, according to the National Transportation Safety Board report on the incident.

The owner had been stationed in Europe for years and was not aware of the need for repair. Once loaded on the Courage, the defect led to the fire. The damage was estimated at $100 million, and the Courage was declared a total loss and most of the cars onboard were scrapped. The legal wrangling among the auto manufacturers is still ongoing.

Mariners focus on fire safety

International regulations and classification societies govern shipboard fire safety regulations including alarms and firefighting equipment.

"We have, as an industry through regulatory and classification society requirements targeting design and operations, put in place preventive safeguards to minimize the likelihood of fire events and recovery safeguards to reduce the severity of consequence," John said.

Under updated international regulations that took effect in 2017, ocean vessel crews must undergo firefighting refresher training every five years to keep their certifications, James Rogin, director of professional education and training at the State University of New York Maritime College, told Supply Chain Dive. Previously crews received firefighting training during their initial certification curriculum but were not required to refresh the training during their careers. However, depending on their service they may have undergone shipboard fire drills and training.

"Fire safety is drilled into their heads from day one," Rogin said.

Managing a fire on a vessel is a mix of fixed systems and crew response gear. For example, the cargo spaces on the Courage were outfitted with a CO2 suppression system that the crew activated in a timely fashion.

The size of the vessel governs firefighting gear for the crew, but with higher levels of automation, there are fewer crewmembers to fight fires. On a 100,000-ton container ship, there may be only 17 people onboard and the vessel is required to carry only four sets of firefighting gear. While some members of the crew fight the fire, others must continue to operate the vessel.

While technology has improved to some extent, such as replacing halon that was found to be a carcinogen with other suppression materials, fire response is much the same as it has always been.

"Firefighting, for the most part, hasn't changed in a long, long time," Rogin said. "You're better off having an experienced crew that has constantly drilled than looking for the latest technology."