As emergency responders continue to fight the destructive path of volcanoes in Hawaii and Guatemala — which are still erupting, weeks after they began — a long-term battle on the economy has already begun.

The volcanoes' short-term effects are undeniable: The eruption of Kilauea on Hawaii's Big Island has destroyed 600-700 homes since May 3, and Fuego, which is more explosive than Kilauea's slow lava roll, has killed more than 100 people in Guatemala. Both have displaced thousands.

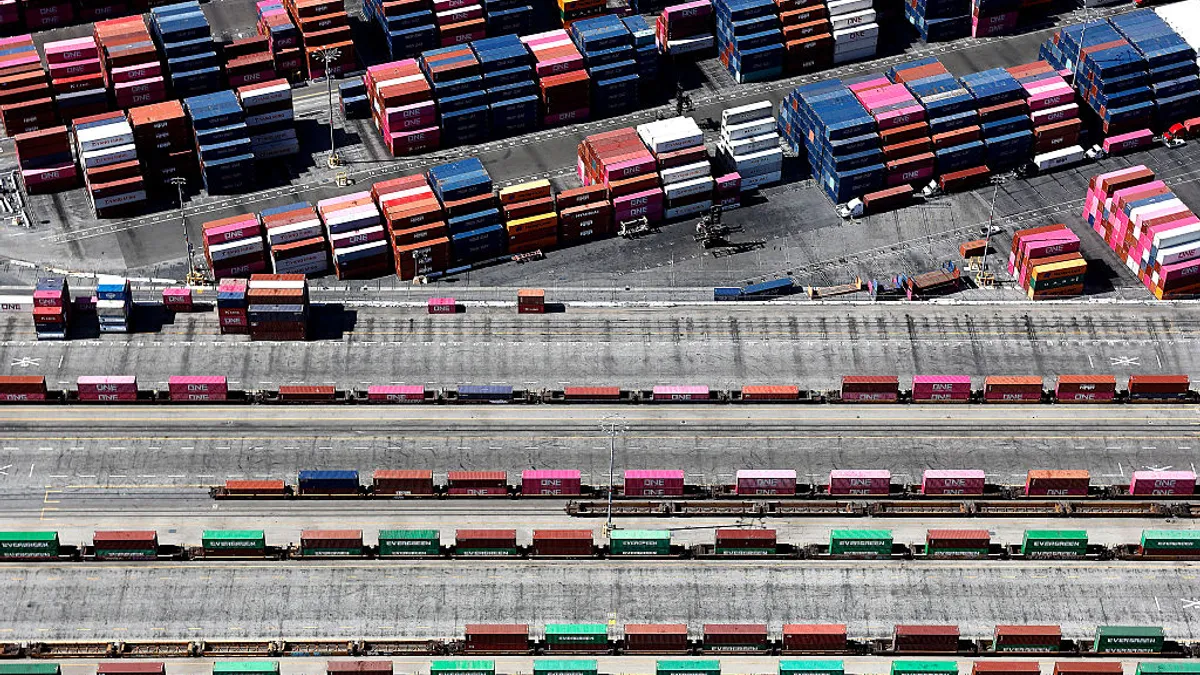

Volcanoes disrupt the supply chain, end-to-end

In the long-term, the volcanoes will hurt more than the people in the evacuation zones and local economies. Wreaking havoc on farms, roads and infrastructure, the volcanoes' destruction will ripple down the supply chain in three ways, reaching companies and consumers.

1. Agriculture

Both volcanoes have severely damaged agriculture in the areas they've reached, which could ultimately have repercussions in the form of higher prices and a shortage of goods.

In Hawaii, Kilauea could destroy as much as 70-80% of the state's papaya production, said Kelvin Sewake, associate dean for extension at the University of Hawaii at Manoa's College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources, in an interview with Supply Chain Dive. Twenty feet of lava rock are covering some farm areas near the volcano.

Kilauea's lava is rolling over large orchid farms located nearby too, which Sewake said will lead to "significant drops" in the state's orchid production. It's also affecting livestock: 1,500 head of cattle were moved north to other ranches on the Big Island. Plant nurseries and other fruit and nut crops have also been overtaken by lava, though not to such a great extent. And lava isn't the only threat: Sulfur dioxide from the volcano kills crops miles downwind, Sewake said.

Recovery will probably take years, Sewake said, because farmers have lost seeds, not just crops and land.

In Guatemala, the volcano has devastated crops —not just with lava and gas near the eruption, but with volcanic ash that has covered nearly half the country. The country's minister of agriculture said the most affected productive sectors have been coffee, basic grains and vegetables, according to Fresh Plaza.

According to one coffee company that sources from Guatemala, Sustainable Harvest, "Beyond the impact of burning lava, rocks, and gas, the ash from the eruption can cause major detriment to coffee plants if it remains stuck to leaves, as it blocks the sun and prevents photosynthesis from occurring." The company noted that its producers have not been affected, but it knows that others have been.

2. Transportation and infrastructure

"There is no doubt that transportation will be affected," said Jonathan Procter, program manager for Volcanic Risk Solutions at Massey University, in an email to Supply Chain Dive."The hazards produced are destructive, destroy roads, bridges etc. Ash fall (associated with Volcan de Fuego) is likely to also affect a much larger area that can disrupt transport routes (air, road, rail etc) that can be difficult to manage or clean."

Kilauea, which is only affecting the southeast corner of the Big Island, has not blocked major highways, though it certainly has shut down roads in the area, said PJ Rogers, assistant professor of supply chain and operations at Brigham Young University Hawaii, in an interview with Supply Chain Dive.

In Guatemala, Fuego has blocked roads and forced the closure of a major highway and the Guatemala City airport.

Volcanologists often neglect the "secondary effects" volcanoes have on businesses through infrastructure destruction — not only halting business by ruining buildings but by contaminating water, cutting off power and disrupting fuel pipelines, Procter pointed out.

"There's also simple things such as ash and gases affecting human health and the inability of people to be able to work or even get to [their] places of work that can have a dramatic effect on business," Procter said.

3. Shifting jobs and resources

Volcanoes affect supply chains in a less obvious way by redirecting jobs and resources, Rogers pointed out. Rescuers and disaster relief officials draw resources — such as sanitation trucks, water and construction workers — to disaster areas.

Hawaii Governor David Ige appropriated $12 million in disaster relief for short-term supplies and repairs in the wake of the Kilauea volcano. Contractors had to bulldoze an alternate escape route after lava blocked highways, USA Today reported.

Lessons learned from Iceland in 2010

This isn't the first time volcanoes have had major repercussions for supply chains.

In 2010, the Eyjafjallajokull volcano in Iceland "sent economic shock waves throughout global supply chains when much of Europe's airspace was closed for six days, canceling 100,000 flights and causing sporadic disruptions that lasted for weeks. The daily flow of $41 billion worth of products moving through the global economy was interrupted," notes IBM in an analysis of volcanic risks on supply chains.

The report details the destructive ripple effect: With transportation blocked, seafood companies lost tens of thousands on products that couldn't get to wholesalers in time; Bangladeshi clothing, dependent on air freight in Europe, piled up in airports; and diamonds needed by Indian processors got stuck in Belgium.

Preparing for the future

For many actors in the supply chain, cognitive-analytics platforms and blockchain may be useful tools for mitigating the effects of disasters in the future, the IBM report notes. Digital solutions can keep everyone along the supply chain up-to-date, helping them soften economic impact and make informed decisions as quickly as possible.

Infrastructure development projects can also take mitigation strategies into account.

"Many mitigation strategies that require additional engineering works can be costly and ultimately prohibitive," Procter said, meaning it's essential to understand the hazards at hand to implement cost-effective solutions. "It is also easier to develop more cost effective mitigation at the initiation of any development or investment in infrastructure development."

For farmers in Hawaii, a volcanic island, there's always risk, Sewake noted. But farmers will probably relocate farther away from the affected area, which will shift the logistics of how their crops travel from the farm.

Humanitarian organizations are on the ground in Guatemala, aware that economic problems won't be stamped out with the volcano and that rehabilitating agriculture is essential to recovery. And on the Big Island, on Friday, Sewake will be speaking at an event with politicians, government agencies, the college, and displaced farmers to discuss ways they can help.

"We don't want to see any farmer stop farming," Sewake said.