When both Amazon and DHL announced they were making moves to open warehouses in Latin America, it brought a spotlight onto a growing region – on the overall economy but especially on e-commerce and how it’s changing the demand for warehousing and supply chain services.

"The e-commerce boom in Latin America is changing the way that companies are servicing their customers," Diego Rodriguez, director of the logistics practice at Americas Market Intelligence, told Supply Chain Dive.

Amazon and DHL may be just the start.

A boosted economy leads the warehouse way

While Brazil is only one Latin American country, it’s a driving force in Latin America’s economy and economic trends. One major trend: e-commerce. It makes up 5% of the country’s approximately $300 million retail market, but has doubled in the last four years and is expected to keep growing at a double-digit pace, according to Reuters.

While e-commerce may be pushing multinational companies to open warehouse facilities in Latin America, Rodriguez said that expanding industries like automotive and healthcare are pushing up demand for warehouses too.

"They are improving their warehousing reach, and they’re changing their supply chains to reduce lead times," he said. "That’s affecting and that’s benefiting the expanding of warehousing facilities in Latin America."

"A complete dismantling of NAFTA will cause severe disruptions in the supply chains of global manufacturers based in Mexico."

Diego Rodriguez

Director of the logistics practice, Americas Market Intelligence

Warehouse demand and supply chain demand feed into each other: the more warehouses there are, the more need for supply chain; the better the supply chain, the more need for warehouses.

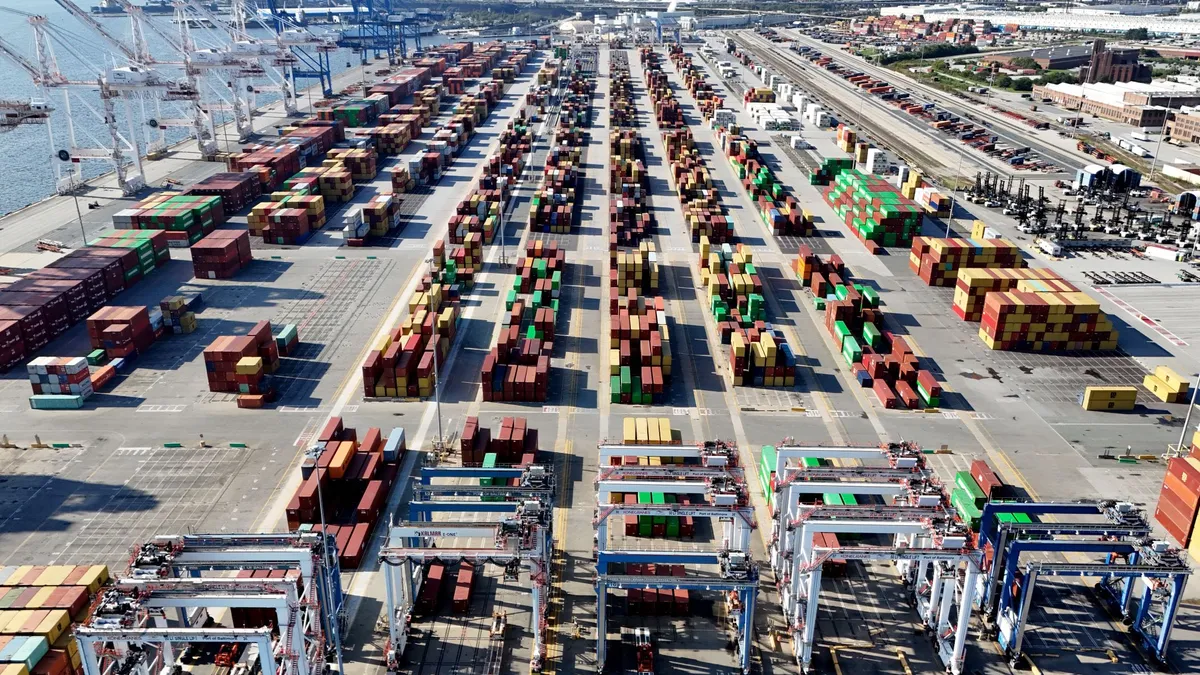

"Many of the ocean carriers are very interested in that area," Nina Luu, co-founder and CEO of supply chain management platform Shippabo, told Supply Chain Dive. That means more interest in supply chain solutions to create "greater trade enablement."

Lack of infrastructure could pose road – or port or rail – blocks

"When you develop supply chain in countries that are just starting to have some real market growth, the challenge is infrastructure," said Luu. "Quite a bit of infrastructure needs to be built – roads, rail, airports, ports. That’s going to be something that, while you may have the warehouse, it takes the country to develop the network."

Such has been the case for the Transnordestina railway in northeast Brazil, which was designed to carry commodities from Brazil to ports and on to markets in China. Despite work beginning a decade ago, the tracks remain unfinished.

Politics pose both perks and pitfalls

Rodriguez said that some investors are also waiting on the sidelines for unrest around 2018 elections to die down. Mexico, which holds its general election in July, could see investor interest in retail and supply chain after the elections are over.

The U.S.’s wobbling stance on NAFTA hasn’t had an effect on foreign direct investment (FDI) levels in Mexico yet, said Rodriguez. In 2017, FDIs in Mexico grew 11%. In the first quarter of 2018, FDIs were 19% higher than in the same quarter of 2017.

That doesn’t mean the horizon’s completely clear though.

"Unequivocally, a complete dismantling of NAFTA will cause severe disruptions in the supply chains of global manufacturers based in Mexico, limiting the growth prospects of the warehouse expansion in Mexico," Rodriguez said. There’s concern that "outsourcing of logistics services will slow down as manufacturers will try to keep under their roof those operations while they understand how to adapt."

He added that in Mexico, less than 40% of firms rely on hiring specialized companies to manage their supply chain and warehousing needs, while more than 85% of firms in the U.S. do; and that NAFTA doesn’t play a substantial role in the rest of Latin America.

"When you develop supply chain in countries that are just starting to have some real market growth, the challenge is infrastructure."

Nina Luu

Co-founder and CEO, Shippabo

On the flip side, Mexico, Chile and Peru are all signers of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), which was ratified early this year. "These three markets see Asia as an alternative to reduce their dependency on the U.S. markets," he said.

In some cases, Peruvian and Chilean exports of food and wine to Asian markets increased tenfold, and he expects the trend to continue, which would drive the need for temperature-controlled facilities in these countries.