From smart watches and glasses to biometric clothing, wearables offer great potential in the supply chain as they enable workers to access information, identify tasks and make their jobs easier and safer.

The benefits make it no surprise that 70% of facilities will adopt wearables in the next five years to help employees increase efficiency, reduce errors and improve performance, according to a recent report by MHI.

But as many of these devices track movement, location and even biometric data, there’s a growing discussion about privacy and how employers should manage and use the information they collect.

Wearables: New levels of safety, ‘enablers of efficiency’

Barcode scanners on wrists and fingers can eliminate manual data entry, while smart glasses can help workers identify packages and products simply by looking at them. Among facilities using wearables or mobile devices within their workforces, 70% said they wanted to create a competitive advantage or support ongoing improvements, according to a study by Deloitte and MHI.

In February 2018, Amazon received patent approval for a wrist band system to gauge the accuracy of warehouse workers’ item and picking location. Walmart filed an application for a patent in March 2018 for a wearable designed to track location, acceleration rate and heart rate, and to use the data to optimize the performance of workers in the warehouse. It will also enable employees to "clock in" or log into computing devices simply by proximity. Walmart's device vibrates to deliver messages and reminders.

"For example, the quantity of steps taken by an employee wearing the wearable device can be monitored and tallied for a task being performed, and this information can be used to determine how the movement of the employee throughout the facility can be modified to improve performance," stated Walmart's patent application.

"What type of stress is the person going through as they perform their daily activities? How is their body responding? It could be beneficial in [physical] environments,"

Randy Bradley

Assistant Professor of Information Systems and Supply Chain Management at the University of Tennessee Knoxville

Wearables are "enablers of efficiency that can demonstrate results," Randy Bradley, assistant professor of information systems and supply chain management at the University of Tennessee Knoxville, told Supply Chain Dive.

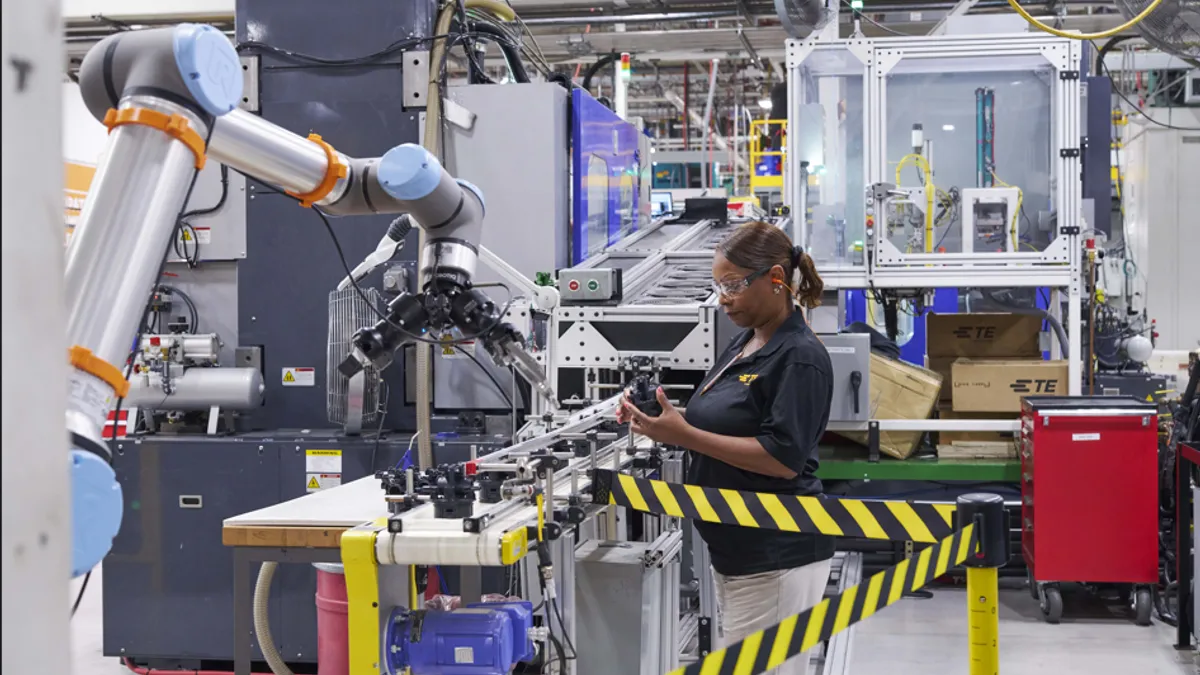

In warehouses with a high rate of picking, reducing "touches" can go a long way in improving efficiency. Many distribution centers are already piloting IoT, automation and AI to work towards a "touchless" supply chain while seeking new ways to enhance the efficiency of humans.

Other wearables, such as fitness trackers and smart garments with biometric sensors, may improve safety by measuring heart rate and how individuals physically respond in their roles, Bradley said.

"What type of stress is the person going through as they perform their daily activities? How is their body responding? It could be beneficial in [physical] environments," Bradley said.

Privacy concerns at the forefront

While most wearable tracking applications are mainly designed to support safety and operational efficiencies, many also collect sensitive data, said Kraig Baker, an attorney with the law firm of Davis Wright Tremaine.

"In general, the more information, the better. But some companies now have more information than they know what to do with, and workers are more sensitive with wearables," Baker told Supply Chain Dive.

Logistics companies such as UPS and FedEx have long tracked and monitored drivers through their vehicles but putting that on the body to track human movement could put companies in some new "ethical waters," Bradley said. Many trackable devices emit data not only when the worker is directly involved in the job, but at all times they’re wearing the device.

"When you take your bathroom break, when you take your lunch, it could be emitting data. Is the organization fully aware of what’s being captured, or are they not even aware of it?" Bradley said.

Generational trends and employee perception could also factor into how wearables are perceived. While they’re generally accepted by younger generations, older generations can be resistant and may see them as micromanagement, Bradley said. Walmart’s patent said the devices would track when workers enter and leave the facilities and how, when and where they move.

A bigger issue is how employers might collect and use biometric data. New sweat sensors can not only detect alcohol but a huge range of biomarkers that could measure health and the potential for disease.

"When you take your bathroom break, when you take your lunch, it could be emitting data. Is the organization fully aware of what’s being captured, or are they not even aware of it?"

Randy Bradley

Assistant Professor of Information Systems and Supply Chain Management - University of Tennessee Knoxville

Even if employers wanted to use such data to encourage healthier activity, the data isn’t reliable enough to make long-term health assessments, said Jacob Krive, clinical assistant professor of biomedical and health information sciences at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

"There are no consumer devices even close to the reliability and even the functionality of FDA approved devices as a wearable that attaches to the body and can measure certain parameters," Krive told Supply Chain Dive. "You can view this data, but you can’t make any serious determinations from it."

Could voluntary adoption turn mandatory?

So far, most employers adopting wearables and tracking devices in the supply chain have done so on a voluntary basis. Many start with incentives such as free devices, insurance discounts, or even cash rewards to entice employees to wear Fitbits and participate in wellness plans, Krive said.

Yet employers may someday soon require employees to wear trackables or measure biometric data when there is an extreme safety risk. Truckers or airline pilots could be required to wear devices that monitor alertness or alcohol in the system, Baker said. Wearable alcohol monitors can estimate blood alcohol content in real time.

While employers can deploy wearables to improve safety and warn their employees to preempt medical conditions, they’ll have to carefully consider reliability and privacy.

"When you know more and collect a comprehensive data set about a person, there is an almost limitless array of actions you could take. And the better we get at using this data, the more lives we’ll save. But there’s a danger of having too much data and it’s not something the average person wants to sign up for," Krive said.

This story was first published in our weekly newsletter, Supply Chain Dive: Operations. Sign up here.