A port labor dispute has boiled over into a full union strike — this time in Canada.

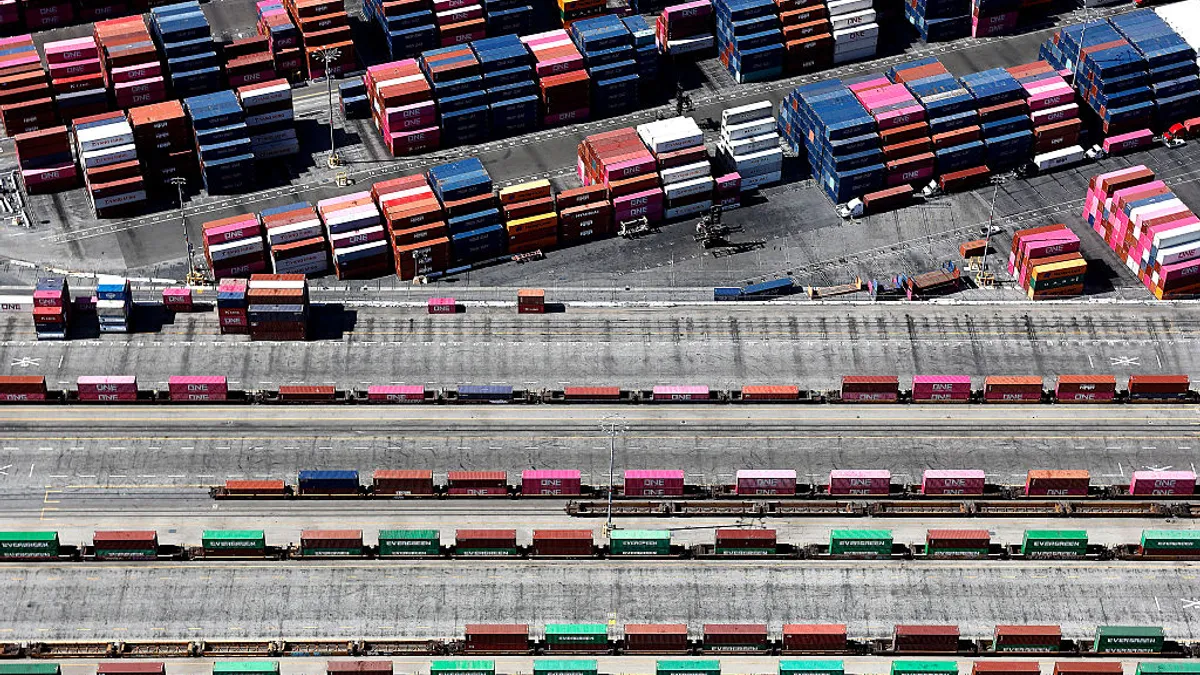

Container terminals at Canada's West Coast ports are at a standstill after the International Longshore and Warehouse Union Canada and the British Columbia Maritime Employers Association reached an impasse in negotiations, leading the union to strike on July 1.

More than six days into the strike, the two parties are still at an impasse on certain contract terms, dashing hopes for a quick resolution. Now, business leaders, politicians and analysts are watching the situation closely, asking: How did we get here? How could the strike end? And what effects could the work action have on supply chains?

Here's what we know so far.

How are supply chains affected?

While ILWU Canada members work at all four port authorities on Canada's West Coast, the British Columbia ports in Vancouver and Prince Rupert are most affected.

The two seaports are among the country's largest maritime gateways, handling roughly a quarter of Canada's trade, according to the BCMEA. Such cargo volumes make the Pacific Coast gateways vital for Canada's trade relationship with the United States and countries in Asia.

The strikes are mostly affecting containerized operations at the seaports, the BCMEA told Supply Chain Dive in an email. Grain operations are protected by federal law, and the two parties also agreed to continue to service cruises.

Still, the impact on containerized products has alarmed several supply chain stakeholders, with some warning in public statements or emailed analyses that a prolonged strike could exacerbate inflation, affect Canada's trade reputation, alter ocean rates and force cargo diversions, among other supply chain spillover effects.

Hapag-Lloyd detailed some of those effects in a website advisory for customers.

The ocean carrier said it expected some route changes for ships, and told customers not to expect any vessels to be loaded or unloaded, any trains to run, nor any containers to be moved at affected ports while the strikes were ongoing.

Why did a strike happen?

When ILWU Canada announced it would strike on July 1, it emphasized three core goals it had during its negotiations: to prevent work from being contracted out, to protect workers from the effects of automation, and to secure better pay.

"Unfortunately, the ILWU Canada Bargaining Committee has run out of options at the bargaining table because the BCMEA and their member employers have refused to negotiate on the main issues, and we feel we are left with no choice but to take the next step in the process," the union said in the press release announcing the strike.

Negotiations continued at the onset of the strike, but talks broke down after the employers’ association walked out on July 3, according to the union. The employers group said that day the union needed a “course change” if talks were to resume.

"ILWU Canada went on strike over demands that were and continue to be outside any reasonable framework for settlement," the employer group said in a statement that day. "Given the foregoing mentioned, the BCMEA is of the view that a continuation of bargaining at this time is not going to produce a collective agreement."

Since then, the two parties have traded allegations — with each saying the other is being unreasonable — via public statements, but have not officially returned to the bargaining table. Federal mediators are communicating with both parties.

Is there an end in sight?

The union, employer group, and business leaders have each publicly proposed a way to end the strike, though Mark Thompson, a professor emeritus at the University of British Columbia's Sauder School of Business, says many of those proposals are untenable.

ILWU Canada has proposed to negotiate directly with the CEOs and presidents of key terminals to resolve a critical clause in the contract — a proposal which would mean bypassing the existing bargaining committee. Thompson said such an offer is unreasonable, as it would be akin to employers asking the union to negotiate directly with workers, rather than their bargaining committee.

By contrast, the BCMEA has proposed negotiations progress into a form of arbitration, instead of the current mediated process, a proposal which Thompson said a union is unlikely to accept, as it would require abandoning its most powerful bargaining tool: the strike.

Meanwhile, business leaders — which are not directly involved in the talks, but fear the impact — are lobbying for parliament to pass back-to-work legislation to end the strike.

"It shows that they really don't believe in free collective bargaining at all when the minute a strike is called and workers walk off, they really want the government to intervene," John Henry-Harter, Labour Studies lecturer at Simon Fraser University, told CBC in an interview.

Thompson added parliamentary intervention would be both politically unfeasible — as parliament is out of session in July — and strategically unsavvy.

"The government takes a long view of this. They're afraid now if they jump in quickly, that'll just be an incentive to the parties to get into an impasse next time," Thompson said.

Still, there is some sign of high-level federal action: Canada's Minister of Transport Omar Alghabra and Minister of Labour Seamus O'Regan Jr. each said on Twitter they had engaged the parties and urged them to continue negotiations and reach a deal soon.

On Thursday, O'Regan said in a tweet he had also met with Acting U.S. Labor Secretary Julie Su, who was widely credited for brokering a deal between longshore workers and U.S. West Coast port employers after they reached a similar impasse.

"The BCMEA and ILWU need to get a deal. Workers across North America are counting on them," O'Regan said in the tweet.