Dive Brief:

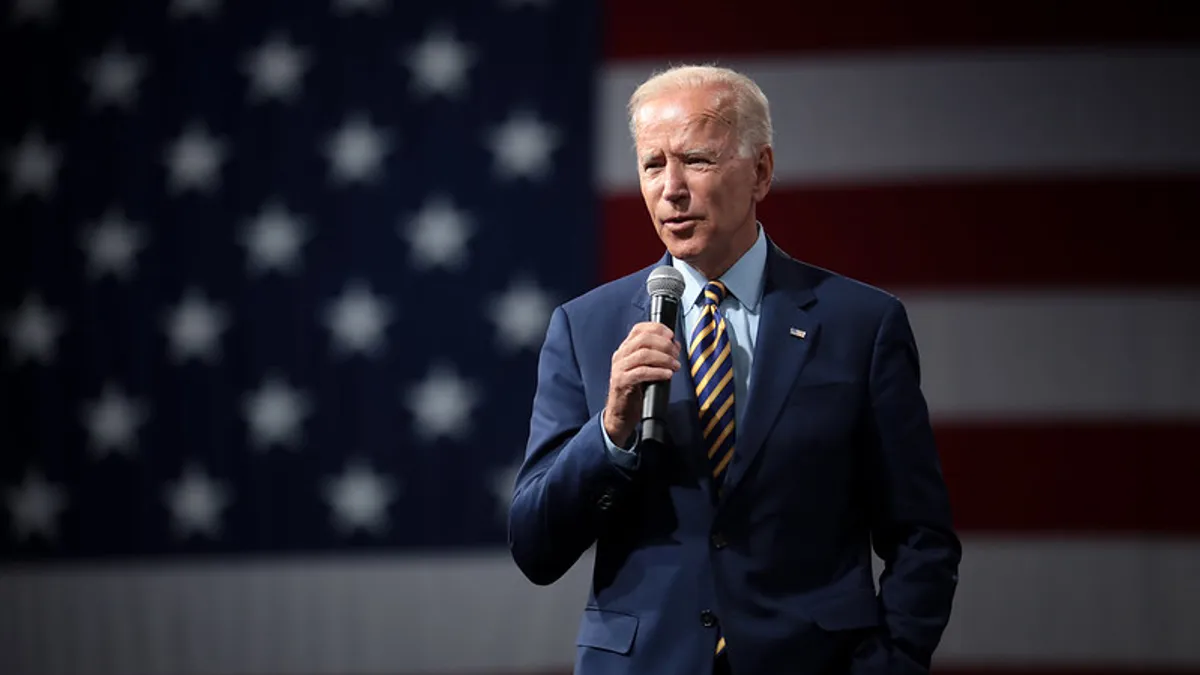

- President Joe Biden signed an executive order Wednesday that will result in a 100-day review of supply chains by the executive branch for pharmaceuticals, critical minerals, semiconductors and large capacity batteries.

- The 100-day review will be followed by a longer year-long review of a broader set of critical supply chains including the energy sector, personal protective equipment, agricultural products, the transportation industrial base and the public health and biological preparedness industrial base.

- "Today, I'm shortly going to be signing another executive order that'll help address the vulnerabilities in our supply chains across additional critical sectors of our economy so that the American people are prepared to withstand any crisis and rely on ourselves," Biden said before signing the Order.

Dive Insight:

The signing of Wednesday's executive order comes after the world witnessed the reality of supply chain disruptions over the past year — from hospitals running low on PPE to automakers struggling to compete with technology companies for semiconductors.

"We heard horror stories of doctors and nurses wearing trash bags over their gown — over their dress in order to — so they wouldn't be in trouble, because they had no gowns," Biden said. "And they were rewashing and reusing their masks over and over again in the OR. That should never have never happened."

And the shortage of semiconductors means U.S. automakers could see their earnings fall by billions this year. Ford could see its earnings fall between $1 billion to $2.5 billion, while General Motors' earnings could slide $1.5 billion to $2 billion, according to a Moody's estimate emailed to Supply Chain Dive. On Wednesday, executive branch leaders, including Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg, met with automakers.

Resilinc CEO Bindiya Vakil said the executive branch's review of these industries will start with an understanding of what the supply chains look like and the location of the suppliers.

"Most companies buy from distributors or they buy from the supplier's broker or something — they don't know where the actual manufacturing is happening," said Vakil, whose company specializes in supply chain mapping. After the location of suppliers is well understood, then companies and the government will have to work to understand what the risks are to that particular region whether it's political or natural disasters.

The Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs and the Assistant to the President for Economic Policy will coordinate the review of the supply chains along with relevant agency leaders.

The executive order on its own is not going to result in changes to the supply chain for multiple reasons, including the fact that industries have been moving manufacturing overseas for decades, Kamala Raman, a senior director analyst at Gartner, said Wednesday.

"The executive order just gives an indication that there's more to come," Raman said.

One concern for U.S. companies is the potential for other countries to prevent exports of certain items that are in high demand.

"What they will find is, for some types of components, you might not have any suppliers in the U.S. today," Raman said. "For others, you might not have any suppliers, but it might be relatively easy to scale up some capabilities."

Vakil said that companies will need to start shifting the way they think about redundant sources of supply. Redundancy costs money, but it also costs money to run out of critical supplies.

"If hospitals and other healthcare organizations look at PPE, not in the context of how much money we spend, but in the context of what is the impact if we don't have it, then PPE would have a very different risk profile," she said.

This is something that some companies are already considering with a recent survey finding that 50% of middle-market manufacturers plan to identify alternative or backup suppliers this year to help overcome disruption experienced during the pandemic.

But creating redundancy in supply chains or bringing manufacturing capacity back to the U.S. to help prevent these shortages in the future will likely require some form of government subsidy, Raman said.

"My guess is without subsidies or incentives of some sort, it is next to impossible to make companies move when there are significant costs to doing so," she said, noting that the U.S.-China trade war has resulted in companies looking at other parts of the world for relocation, not the U.S.

The U.S. is often more expensive than other countries when it comes to manufacturing as a result of higher labor costs and consumers aren't great about prioritizing expensive products just because they were made in America, Raman said.

But to help with the needed subsidies the Biden administration is already looking to Congress for some funding to make this happen in the semiconductor sector.

"I'm directing senior officials in my administration to work with industrial leaders to identify solutions to this semiconductor shortfall and work very hard with the House and Senate," Biden said Wednesday. "They've authorized the bill, but they need ... $37 billion, short term, to make sure we have this capacity."

Last week, multiple businesses and industry associations wrote a letter to the Biden administration asking for action on the semiconductor issue. Those groups applauded the Executive Order, including Bob Bruggeworth, the CEO of Qorvo, and the 2021 Semiconductor Industry Association board chair.

"As part of this effort, we urge the president and Congress to invest ambitiously in domestic chip manufacturing and research," Bruggeworth said in a statement.